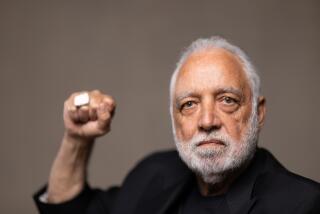

Saluting a gay rights pioneer

- Share via

When a small mob of gay men armed with flowers marched into the LAPD’s Harbor Division station late that August night, the desk sergeant appeared startled.

“We’re here to get our sisters out!” said the group’s ringleader, Lee Glaze, co-owner of a popular Wilmington gay bar that had been raided hours earlier.

It was 1968, and Los Angeles police had arrested two of Glaze’s male patrons when a plainclothes officer saw one slap the other playfully on the rear.

Glaze, an unapologetically effeminate man known as “Lee the Blond Darling,” was furious.

He took to the bar’s stage, rallied the crowd and asked if a florist was among them.

When someone raised a hand, Glaze told him, “Honey, go get every flower in your shop.”

The flower vigil, which lasted until police released the men on bail, would become a footnote in the gay rights struggle, overshadowed by the Stonewall Inn riots in New York a year later.

This weekend, Glaze was honored by the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence, a gay rights group recognizable by its membership of men who don nun habits and wear heavy, colorful makeup.

Part of the reason Glaze was chosen for “sainthood” by the Sisters was to highlight that history of discrimination and his role in fighting it, said Chris Recio, a.k.a. Sister Tragedy Ann. Other saints include assassinated San Francisco Supervisor Harvey Milk and comic Margaret Cho.

“Few people know of Lee,” Recio said. “But he was the genesis of the early movement in L.A.”

At age 73, Glaze now lives in Hollywood’s Triangle Square Apartments, an affordable-housing complex for aging lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender individuals. Although he suffers from cataracts and a back injury, Glaze excitedly recalls his early activism.

“These kids today have no idea what it was like back then,” Glaze said. “It was an adventure when you went out. You had to be careful.”

A city ordinance prohibited men from dancing with one another. At some gay night spots, skittish bar owners would buzz through only trusted patrons, an effort to keep out undercover vice officers.

Gay men dared not challenge authorities. Rumor had it that police would “out” closeted arrestees to their families and employers.

The Rev. Troy Perry, whose date was arrested that August night, credits the petal protest for inspiring him to found the first gay church in Los Angeles, the Metropolitan Community Church.

“I’d never seen anyone stand up to the police before,” Perry said. “Those may have been some nellie fists, but they were brave fists.”

Glaze didn’t set out to become an activist.

“I had no idea what I was doing,” he said. “I ran a … good bar. I was just mad the cops kept coming around.”

In an effort to protect his customers, Glaze said, he made regular visits to the police stations in the area, committing to memory the faces of any vice cops he saw.

If they came into his bar, he’d play “God Save The Queen” to warn patrons they were being watched.

Other times he’d jump onstage and take the microphone: “Boys, I don’t know what’s burning, but something is burning! It’s getting awfully warm in here.”

Glaze’s fierce support came with a price. The Patch, which attracted customers from all over Southern California, closed after two years.

Black-and-white photos of the era are displayed prominently in his cramped apartment, as well was murals he’s painted of Greek gods.

In one snapshot, he’s interviewing an underwear-clad contestant for the first-ever Mr. Groovy pageant. In another, he’s making a dramatic entrance to a glamorous red-carpet event in Hollywood.

“I just had a ball then,” he said.

Despite his physical ailments, Glaze is a live wire, whizzing around his building in an electric wheelchair and peppering fellow residents with greetings.

He continues to make appearances at gay rights functions, fighting for what he calls the last hurdle: federal marriage rights for same-sex couples.

He says the strides that gay civil rights activists have made in recent years have made the younger generation complacent. The struggles Glaze and his compatriots endured seem so foreign to them, he said.

He also laments that some of his more able-bodied neighbors in this elderly community aren’t nearly as active as he is.

“These queens,” he said. “They’re just so old!”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.