Seeking shoppers in Westwood Village

- Share via

Remember Westwood?

Before multiplexes changed film-going, fans stood in line for hours outside Westwood Village movie palaces to see such blockbusters as “The Exorcist.” Before chain stores and Amazon wrested business from independent booksellers, readers browsed the racks of Hunter’s, Campbell’s and Westwood Books.

And before Old Pasadena, Universal CityWalk and Santa Monica’s Third Street Promenade came on the scene, the triangular-shaped district south of UCLA was the hippest place to be in L.A. on a Saturday night.

But in the 20 years since gang intimidation and violence chilled Westwood Village’s groovy vibe, the area has struggled -- with spotty success and many setbacks -- to reclaim its former zing. Meanwhile, other shopping options have sprung up, including the faux village known as the Grove at 3rd Street and Fairfax Avenue, and Westfield’s revitalized Century City shopping center.

“Is it realistic to think Westwood is going to come back to anything like it was, a major shopping destination?” mused Jeff Abell, a co-owner of Sarah Leonard Fine Jewelers, a 62-year village fixture. “I think nothing substantive is going to happen unless the landlords sit down . . . and work out a cohesive plan.”

Given Westwood Village’s location amid the “platinum triangle” of Bel-Air, Holmby Hills and Brentwood -- not to mention UCLA’s 43,000 students and faculty members -- it’s a wonder that the place has ever been anything but a dazzling success.

Village devotees say the lack of a singular vision and the area’s notoriously difficult parking are squelching any hope for a robust comeback. But a burst of construction activity promises to spur momentum.

On Glendon Avenue, a block east of Westwood Boulevard, the first of an anticipated 700 tenants have moved into the 350-unit Palazzo Westwood Village even as workers scurry to complete the project. Nearby on Lindbrook Drive, the former site of a Flax art supply store, developer Kambiz Hekmat has broken ground on an “extended stay” boutique hotel that will have shops and restaurants. A modernist retail project from developer Ron Simms is planned at the site of the recently razed 1,100-seat Mann National Theater, where “The Exorcist” had its Los Angeles opening in 1973.

Merchants and landlords say they hope that the activity will bring well-heeled customers. They warn that it is too early to tell how successful Casden Properties Inc., headed by billionaire developer Alan Casden, will be in attracting tenants. Monthly rents for an 860-square-foot, one-bedroom unit start at $2,750; three-bedroom town homes range from $6,900 to about $7,500.

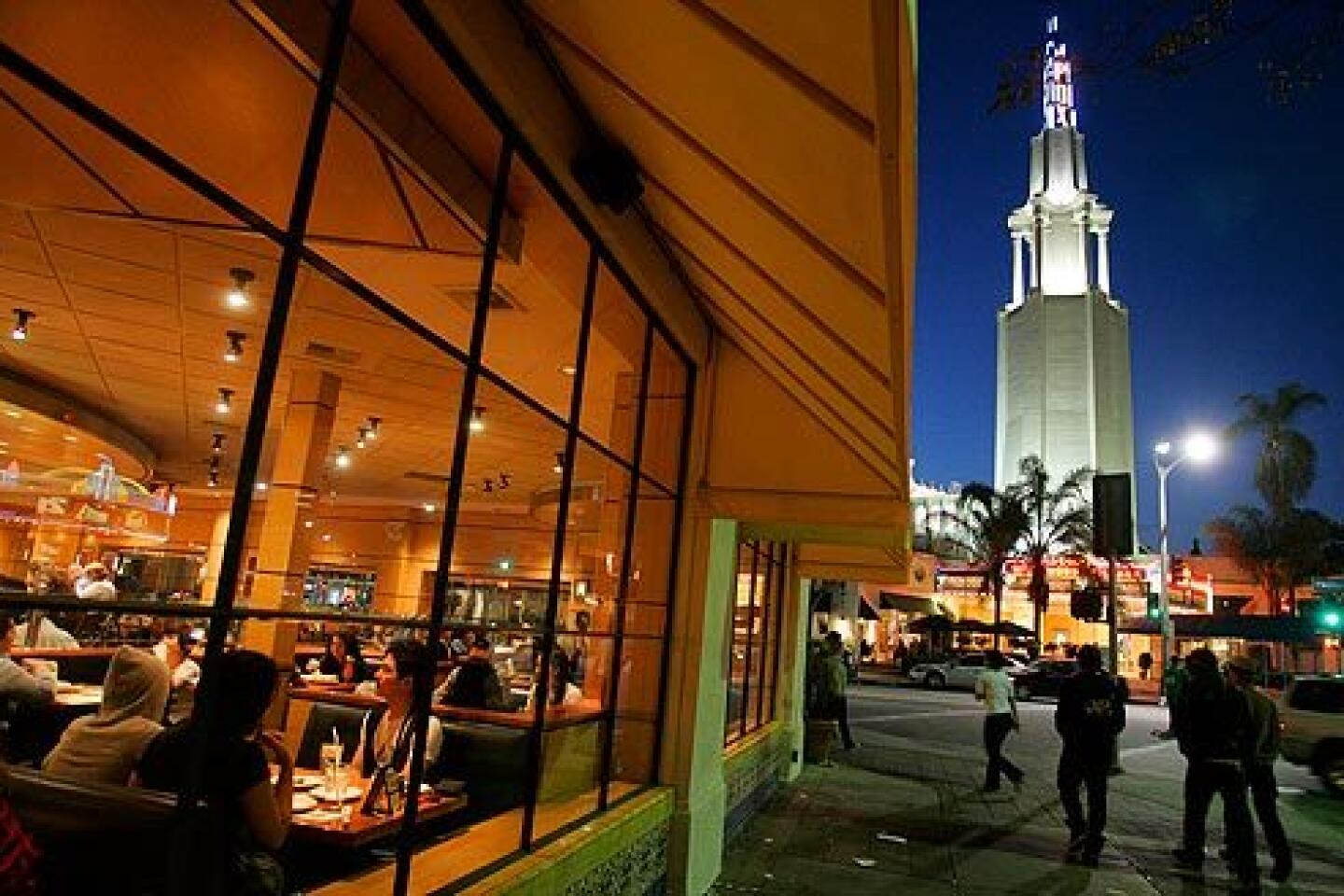

Westwood Village is hardly a wasteland, as midday traffic jams attest. Pedestrians still crowd the sidewalks, particularly at lunchtime, when office workers spill out of Wilshire Boulevard high-rises. New eateries such as the Stand and Chipotle are finding customers, as are Urban Outfitters, American Apparel and Active Ride Shop, which sells skateboarding gear and apparel.

Ralphs, Whole Foods, the Geffen Playhouse and the Hammer Museum are big draws. June’s Los Angeles Film Festival (of which the Los Angeles Times is a presenting sponsor) will be the third in the village, with visitors expected to spend about $30 each beyond the cost of tickets.

But the village, at its inception in the 1920s one of the most immaculately planned and beautifully laid out of commercial areas in the nation, has become an architectural and mercantile mishmash. Much of the original Mediterranean charm and uniqueness went missing long ago.

“As far as I’m concerned, most of it is ruined with giant buildings,” said Marc Wanamaker, a historian who is writing a book about Westwood Village.

In 1970, a 24-story office building now known as Oppenheimer Tower replaced Truman’s drive-in, a popular hangout at Wilshire and Westwood boulevards. “That,” Wanamaker said, “changed the village. Between then and now there has been a total transformation.”

Westwood still attracted throngs of visitors until the late 1980s, but they grew wary when gangs began cruising the streets and harassing pedestrians. In January 1988, 27-year-old Karen Toshima, a bystander celebrating a job promotion, was killed in a gang shootout.

“That was it,” Wanamaker said. “Nobody showed up the next weekend. It was a ghost town.”

Commercial rents have yet to approach the 1988 peak, when annual leases were going for $70 a square foot, said Stanley McElroy, a vice president with CB Richard Ellis, a commercial real estate firm. Today they range from $36 to $60.

Even longtime property owners such as Topa Management Co. -- billionaire John Anderson’s real estate firm -- are struggling to lure and keep high-quality tenants. The Gap vacated a Topa building in late 2003, and Ann Taylor Loft will leave at the end of June.

Along Westwood Boulevard in the village core, “For Lease” signs have popped up like fungi after a rain, and homeless men and women hunker down with blankets and stuffed plastic bags in the doorways of vacant storefronts. Long gone are Desmond’s Clothing Store and Bullock’s Westwood, which served as magnets for discriminating shoppers.

All but one bookstore and many of the movie screens have left. As they have for years, merchants continue to bemoan the lack of easily accessible parking.

Westwood Village was launched in the late 1920s by Janss Investment Co., a large residential real estate developer run by brothers Harold and Edwin Janss and their father, Peter. In 1926, when UCLA chose a 384-acre section in a tract called Westwood Hills for its home, Harold Janss began preparing a meticulous plan for a commercial village.

He hired big-name architects and instructed them to hew to a Mediterranean theme, with clay tile roofs, decorative Spanish tile, paseos, patios and courtyards. Buildings situated at strategic points, including theaters and gas stations, incorporated towers to serve as beacons for drivers on Wilshire.

Janss selected the merchants, including many special boutiques, and determined where they would go. The village opened in 1929 with 34 businesses; a decade later, the Depression notwithstanding, there were 452.

James S. Rosenfield, who owns and leases properties in Westwood, said bringing the village back will take that same commitment to quality. The village’s many large and small property owners have been unable to agree on reviving a defunct business improvement district, and that, he said, has hampered efforts to create a parking plan and clean up the village.

“Westwood has dug itself into a bit of a hole,” he said. “People need to have a vision other than who will pay the highest rent. . . . If it’s the seventh yogurt shop . . . arguably that’s not the best thing to do.”

Rosenfield spent years restoring the Brentwood Country Mart and is pushing for a similar approach in Westwood Village. “We need to make it look like it once did, with grassy, palm-lined medians and less concrete,” he said. “If we think of it as this wonderful retail village, with wide sidewalks and wonderful shops, Westwood can be rejuvenated.”

Over the years, powerful Westwood homeowner groups have defied developers who wanted to build hotels or turn Glendon Avenue into a pedestrian mall. The Casden project generated heated opposition from neighbors before winning city approval in 2004, and critics continue to decry its density.

But the strong desire to recapture the vibrancy of old helps explain why some neighborhood activists who battled to scale back the Palazzo now view it as a possible saving grace.

The 4.3-acre complex, with 50,000 square feet of retail, will soon welcome a Trader Joe’s, a drugstore, a coffee shop and two eateries. And for the first year it will offer two hours of free parking to the public.

“I remain concerned that it’s a very dense project,” said Laura Lake, a longtime activist. “On the plus side, hopefully, there will be people all the time in the village.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.