Quiet End to Muslim Brothers’ Trial

- Share via

DALLAS — A federal jury could decide as early as today whether five Muslim brothers in Texas violated export regulations when they shipped computer parts to Libya and Syria, countries that have been labeled state sponsors of terrorism.

But the three-week-long trial is wrapping up with considerably less fanfare than the case began with, leading to renewed accusations that President Bush’s war on terror often targets domestic politics as much as international terrorism.

Federal officials have accused the brothers of laundering money for Hamas, a Palestinian militant group, using their now-defunct computer company. Bush has alleged that a Texas-based charity connected to the brothers was also a front for Hamas and was used, among other things, to route money to the families of suicide bombers.

But while U.S. Atty. Gen. John Ashcroft once labeled the brothers “terrorist moneymen,” charges specifically related to terrorism have been dropped from the trial and are tentatively scheduled to be heard in a second proceeding this fall.

What’s left for now are allegations that the brothers improperly shipped computer parts to customers in Libya and Syria -- not to the governments themselves.

The customers included a Toyota dealer and a bookstore. Prosecutors have yet to utter the word “Hamas” in court.

And while Justice Department lawyers have said the hardware could have been used for military purposes, the brothers’ representatives insist that most of it was so dated that it couldn’t even have been used to play the latest computer games.

Some legal experts have said this is the latest example of the Bush administration overreaching in its prosecution of the war on terror -- and tossing aside civil liberties in the process.

“This is exactly what the Founding Fathers were thinking about when they enacted the Bill of Rights,” said David Nevin, a defense lawyer in Boise, Idaho. “The Bill of Rights wouldn’t be there if it wasn’t the tendency of government to reach out and take all the power it can to try to do the things it wants to do.”

Nevin recently represented an Idaho graduate student, 34-year-old Saudi national Sami Omar Al-Hussayen, whom the federal government had accused of using the Internet to foment and finance terrorism. A jury last month rejected those charges, brought under the USA Patriot Act.

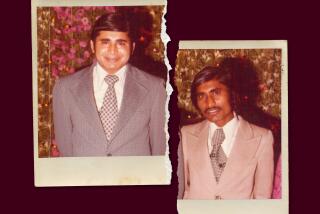

In the Texas trial, the brothers -- Ghassan Elashi, Bayan Elashi, Basman Elashi, Hazim Elashi and Ihsan Elashyi -- are accused of export violations, making false statements and money laundering. They have pleaded not guilty and face prison terms of 115 years apiece if convicted on all counts, according to government documents.

The defendants, their lawyers and federal prosecutors, citing a gag order, declined to comment for this story.

Members of a prominent Palestinian family, the Elashi brothers are accused of conspiring to use InfoCom, their former firm, to illegally ship the computer parts between 1997 and 2000. The United States has labeled Libya and Syria state sponsors of terrorism since 1979, although the U.S. recently began to normalize relations with Libya. Accounts of the value of the computer parts vary widely, from less than $60,000 to nearly $500,000.

Authorities became interested in the men, aged 42 to 51, before Sept. 11, 2001, government officials said, because of an alleged relationship they had with Mousa Abu Marzook, a Hamas leader. Marzook is now thought to live in Syria, but he was a legal resident in the United States until the early 1990s. Israeli officials think he has planned and financed suicide bombings and other attacks.

In the 1990s, Marzook’s family was the source of a $250,000 investment in InfoCom. The government said the money came from Marzook; lawyers for the brothers argued that it came from Marzook’s wife -- the brothers’ second cousin. Marzook also is thought to have given money to a charity, the Holy Land Foundation for Relief and Development.

The United States shut the charity down in 2001, alleging that it was a front for Hamas, and seized its assets; no charges have ever been brought in connection with Holy Land.

Paul Rosenzweig, a senior legal research fellow at the Heritage Foundation, a conservative think tank in Washington, said it could be that the brothers’ prosecution had been undertaken with unusual aggressiveness. But, he said, the government must be allowed to go to extraordinary lengths to combat terrorism -- even if it risks appearing heavy-handed at times.

“The civil libertarians believe that terrorism isn’t different from anything else, that nothing should change in the way that we use our laws,” Rosenzweig said. “The government’s point is that terrorism is different. And frankly, I think that they are right. The risk of error -- of a false negative, or of missing a terrorist -- is different. If we miss John Gotti, he’s not going to plant a nuke in New York or Los Angeles.”

Gotti, who died in 2002, was once the leader of the Gambino crime family.

But critics point to several cases that were brought by the federal government recently under the guise of the war on terrorism -- only to unravel when scrutinized by the justice system.

The cases include those brought against Al-Hussayen, the Idaho student; and Brandon Mayfield, a lawyer in Portland, Ore. Mayfield, a convert to Islam, was jailed for two weeks after the FBI wrongly linked him to fingerprint evidence in deadly March train bombings in Madrid. Mayfield has suggested that he was targeted because of his faith.

Then, this week, the U.S. Supreme Court rejected the Bush administration’s contention that it could hold “enemy combatants” indefinitely, without access to lawyers or the legal system.

Justice Sandra Day O’Connor wrote that “a state of war is not a blank check for the president.”

“There is a major effort on the part of the federal government and the Bush administration to put teeth into the Patriot Act. But some of those teeth have been pulled,” said Rand C. Lewis, director of the University of Idaho’s Martin Institute for Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution. “Some of these cases are not very strong. And the public is watching.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.