Details emerge of a deadly day in Haditha

- Share via

HADITHA, IRAQ — The day that would produce the biggest case of alleged atrocities by U.S. troops in Iraq began simply.

On Nov. 19, 2005, a squad of Marines moved out before dawn to take hot chow and a code-changing device to an outpost a few miles away. They planned to get back while the sun was barely rising over the Euphrates River.

The Marines from Kilo Company, 3rd Battalion, 1st Regiment, had arrived in Haditha six weeks earlier from Camp Pendleton. In that time, there had been few signs of insurgents -- and Marines had searched dozens of houses without a firefight or casualty.

Still, nearly 50 Marines from the battalion that preceded them had been killed or severely wounded in the area that the U.S. calls the Triad -- Haditha, Barwanah, Haqlaniya. The year before, insurgents in Haditha had massacred dozens of Iraqis accused of collaborating with U.S. troops.

Two days before the Nov. 19 convoy, intelligence officers had warned that foreign fighters who entered from Syria were waiting to ambush Marines in Haditha, 80 miles from the border, and would probably hide behind civilians.

Some of the 12 Marines on that morning’s mission had never been in combat. Others were veterans of bloody house-to-house fighting the year before in Fallouja.

Sgt. Frank D. Wuterich, the squad leader, had never seen combat, but had impressed his superiors as a mature, natural leader. He was a seeming contradiction: a 25-year-old with a boyish face and an understated manner -- and menacing-looking tattoos on both forearms.

After a lengthy briefing about the route, the dangers and the tactics to use in case of attack, Wuterich said simply, “Let’s get it done, Marines.”

With that classic order, the four-vehicle convoy left Firm Base Sparta about 6 a.m., rolling down a wide road the Marines had named Route Chestnut.

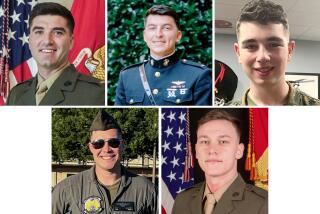

Before the sun rose high, one Marine and 24 Iraqi civilians would be dead. Nineteen months later, three enlisted Marines face charges of murder and four officers are charged with dereliction of duty.

At Camp Pendleton, preliminary hearings are underway on whether the cases should be sent to courts-martial. Those hearings, and interviews in Haditha and in the U.S., have put many new details of that day onto the public record.

‘I’m not seeing 4’

The terrain of Haditha is ideally suited for guerrilla warfare. Its terraced streets sloping down to the Euphrates provide good vantage points for snipers. Many homes have solid masonry walls in the front and back, perfect for sneaking a look at passing convoys and then ducking to avoid detection, a tactic Marines call “turkey-peeking.”

As the Marines set off, they scanned the road for explosives and nearby yards for snipers. They saw no one.

The drop-off went smoothly, and the Marines began the return trip about 7 a.m., shortly after sunrise. Riding with them were several Iraqi soldiers who were to take part in joint patrols.

Slowly the convoy went down River Road and then took a left onto Route Chestnut. Near the intersection of Route Chestnut and the road the Marines call Route Viper, an enormous explosion erupted beneath the convoy’s last vehicle, a Humvee.

“I’m not seeing 4, I’m not seeing 4,” yelled Lance Cpl. Justin L. Sharratt, a Fallouja veteran who was manning the gun turret in the first vehicle.

“Fourth vehicle is hit, T.J.’s dead,” yelled Lance Cpl. Rene Rodriguez.

T.J. was Cpl. Miguel Terrazas, 20, a popular Marine with a cheerful, blustery manner. He was from El Paso, but buddies called him T.J. in reference to rowdy times they had shared in Tijuana.

The blast killed him instantly. Parts of his torso were strewn 100 yards from the burning Humvee. His severed legs remained in the driver’s seat.

Lance Cpl. James Crossan, 20, and Lance Cpl. Salvador Guzman, 19, were wounded -- Crossan blown out the right door and pinned under metal debris. Brian Whitt, a Navy corpsman, rushed to him with morphine.

“Help me, Doc,” said Crossan, barely conscious. Both Guzman and Crossan would survive.

Wuterich took charge. He called Sparta to report that Marines were “in contact” with the enemy.

At Sparta, another group, called a quick-reaction force, was standing by, prepared to race to the aid of the squad that had left. First Lt. William Kallop, the platoon commander, was part of that unit. It was the 24-year-old Kallop’s first combat experience.

Meanwhile, a white Opel sedan approached the scene of the blast, with five young Iraqi men inside.

Marines shouted for the car to halt and pointed their M-16s at the windshield. The car stopped, and the five men got out.

To this point, no details of the day are in dispute. From this point on, there would be much to question.

The five Iraqis were quickly riddled with bullets by the Marines. Wuterich told his superiors that night that the five had begun to run away. Under Marine rules of engagement, if suspected bombers run from the scene of an attack, they can be shot, even in the back.

Wuterich said that he and Sgt. Sanick P. Dela Cruz, 23, shot the five because they suspected them of being spotters or triggermen.

For months, Dela Cruz backed Wuterich. But then he was charged with murder. Prosecutors offered to drop the charge in exchange for his testimony. At a hearing at Camp Pendleton in early May, he gave a new account.

The five were standing still, with their fingers locked behind their necks, when Wuterich began firing, he said. “They were just standing, looking around, had hands up,” he testified.

Dela Cruz admitted that he “sprayed” the bodies while they were on the ground and then, in a show of anger, urinated on one of them. He said Wuterich told him to lie and say that the Iraqi soldiers the squad was transporting had killed the five.

Minutes after the five men had been killed, Kallop arrived. He did not ask why the Marines had opened fire.

“We had stuff going on, and I wasn’t going to say, ‘Stop the presses. Take me step by step,’ ” Kallop said, testifying this month in exchange for immunity from prosecution.

Kallop said that Wuterich told him gunshots had been coming from the south and that he gave the order to search a row of houses about 100 yards across a vacant lot.

“I decided that the houses were most likely where fire was coming from, and I told Sgt. Wuterich to ‘clear south,’ ” Kallop said.

Whether Wuterich’s squad was under fire after the bomb blast remains uncertain. Some Marines told investigators they heard shots, others said they did not.

Kallop remained crouched behind a Humvee for protection. Wuterich and two veterans of Fallouja -- Sharratt, 21, and Lance Cpl. Stephen B. Tatum, 24 -- headed for the houses.

“They did not have grief in their eyes,” Kallop said. “They were operating as we trained them.”

‘Where are the bad guys?’

Wuterich and Tatum later told superiors that when they entered the first house, they heard the “racking” sound of an AK-47 being cocked for firing and responded by lobbing grenades and firing their M-16s. They said they saw an insurgent fleeing from the first house to the second, and followed him with more grenades and gunfire.

Within minutes, 15 civilians inside were dead, including three women and seven children.

An old man’s legs were severed by a grenade. Another man was shot in the eye. A child was decapitated by gunfire or grenade blasts. Several victims apparently were sitting with their backs to a wall when shot, investigators later determined.

Some of the dead children, ranging in age from 2 to 13, were on a bed. The women appeared to have been trying to shield them. A teenage girl was shot in the head.

Only after the gunfire was over did Kallop approach the houses, accompanied by Cpl. Hector Salinas, a member of Wuterich’s squad. Kallop testified that he was shocked when he found no weapons inside the houses and that none of the males wore the kind of military garb associated with insurgents.

“I looked at Cpl. Salinas and said, ‘What the crap? Where are the bad guys?’ ” Kallop said. “He looked as surprised as I was.”

Still, Kallop asked few questions of Wuterich and the others. “Maybe because I wanted to keep on pushing on what I was doing and come back when I had a chance,” he said.

Wuterich, Sharratt and Salinas then decided to “clear” houses on the north side of the crossroads.

Sharratt said that men had been spotted turkey-peeking over a wall. That, he said, was enough to indicate hostile intent.

In the first house, they were greeted by women and children, Sharratt said. But in the second, he said, he heard the sound of AK-47 racking and saw a man with an AK-47 in a doorway.

“I jumped back and bumped into Sgt. Wuterich,” he said. “After that my training took over, and everything that my first sergeants and squad leaders had ever taught me came into play.”

He said his machine gun jammed so he pulled out his 9-millimeter handgun and began blasting.

“After I ran out of ammo, I yelled, ‘I’m out,’ and Sgt. Wuterich entered the room and fired his M-16 at the men too,” Sharratt said.

Four Iraqi brothers lay dead -- three on the floor, one in a closet. The three had each been shot in the head. The brother in the closet was killed by M-16 fire.

Sharratt said he took two AK-47s from the dead men and gave them to Tatum.

Although there are records of two AK-47s being seized that day near Chestnut and Viper, the Marine assigned to collect captured weapons testified that he did not know whether they were seized as Sharratt said, or came from somewhere else.

Relatives of the dead brothers told investigators they witnessed Marines herding the four into a back bedroom and then heard shots being fired. Wuterich and Sharratt have denied their account; Sharratt passed a lie detector test on the issue, according to documents presented at his preliminary hearing.

Commander arrives

Lt. Col. Jeffrey Chessani, the commander of the 3rd Battalion, was in his command center at the 10-story-tall Haditha Dam, 12 miles away, listening to radio reports from the scene.

His actions, and those of his fellow officers over the next few hours, would bring into question the attitude of Marine commanders toward the killings. Were they covering up for their men or simply trying to survive a violent, chaotic day?

Chessani was on his third tour in Iraq. He had served as a battalion executive officer during the April 2004 fight in Fallouja and then as a regimental operations officer during the November 2004 fight in that city, both times earning high ratings from his bosses.

Now Chessani had his own battalion and his troops were “in contact” for the first time in Haditha. Chessani ordered the launch of an unmanned aerial surveillance vehicle called Scan-Eagle.

By the time the craft was airborne, the action at Chestnut and Viper was largely over. As Chessani and other officers watched on large screens, Scan-Eagle beamed back video of another engagement, an intense gun battle at a palm grove about 1,000 yards from the intersection.

The battle seesawed. Marines sent as reinforcements were ambushed. The insurgents were well armed, firing AK-47s and rocket-propelled grenades.

Insurgents were seen running from one place to another. One was spotted going into a house, then emerging in different clothes and carrying a baby.

The Marines nodded: typical insurgent ploy, hiding behind women and children. They assumed the same tactic had been used by the insurgents who they believed had fired at the Marines at Chestnut and Viper after the bombing that killed Terrazas.

That blast “was the cataclysmic event that started the day’s events,” said Maj. Sam Carrasco, the battalion operations officer. The Marines ended it with a blast of their own -- a 500-pound bomb on a house in the palm grove.

Chessani arrived at the grove in the afternoon. Nine of his Marines had been wounded there, none fatally. He inspected the rubble and looked at the spots where the Marines had been hit.

But when he suggested driving to the houses where Wuterich and his squad had killed the civilians, Sgt. Maj. Edward Sax, the battalion’s senior enlisted man, noted that it was getting late and warned against remaining “outside the wire” after dark.

Besides, everything they needed to know about the Chestnut-and-Viper skirmish was already known, Sax said. Insurgents attacked and Marines responded. The pair went to Sparta and then back to battalion headquarters at the dam.

By nightfall, Chessani’s analysis was set. His Marines, he decided, had been subjected to a “complex, coordinated attack” starting with the bombing that killed Terrazas, the kind of ambush they had been warned by intelligence officers to expect.

What he was hearing from the Marines fit the scenario: The Iraqi men in the Opel had attempted to flee, shots were coming from the houses, weapons were found in the car and the houses, Marines clearing the houses were confronted by insurgents with AK-47s.

“Investigation was not in our lexicon,” said 1st Lt. Adam Mathes, Kilo Company executive officer. “Our understanding is that we were set up in a situation where it was kill or be killed.”

Investigators and prosecutors would eventually label as false each of the assertions that Chessani had accepted uncritically as fact. No weapons were found near the car, no AK-47 shell casings could be confirmed as being in the houses, and no signs existed that insurgents had been firing from them, according to testimony.

Reliving the day

In the nighttime hours, as Marines reassembled at Sparta, officers and senior enlisted men concentrated on trying to help the young Marines cope with the violence that had been done to their own. Some Marines had tears in their eyes. Others were writing letters to their families or sitting silently.

“We had to get ready the next day to go outside the wire again,” Kallop said.

Late that night, Kallop wondered aloud about whether his order to Wuterich to “clear south” had been interpreted to mean the Marines could employ the tactics used in Fallouja.

“He said he didn’t know if when he said, ‘Clear the houses,’ ... he’d given an order to kill everyone,” Mathes testified.

Officers ordered Marines to take the bodies from the three houses near Chestnut and Viper to the city morgue. Previous battalions had always just left the bodies of Iraqis they had killed where they had fallen.

“We’re better than that; we clean up after ourselves,” Mathes said.

Marines who balked at removing the bodies were told to shut up and go back to work. Iraqis at the morgue vomited when they saw the dead children.

Even before the bodies were removed, officers were filing required reports with their superiors at the regimental and division headquarters about the civilian deaths. None presented a full picture.

One report, over Chessani’s signature, indicated incorrectly that Chessani had inspected the scene of the civilian deaths. The report, sent about midnight, did not mention that the civilians had been family members killed inside their homes, nor did it mention any doubts Kallop may have expressed.

On Nov. 22, Maj. Gen. Richard Huck, then commander of the 2nd Marine Division, came to Haditha. He left satisfied that the civilian deaths were combat-related, and that a briefing he received provided a “plausible sequence of events.”

But by late January, the official version was being challenged, first by the Haditha town council, which asserted that Marines had “executed” the civilians, and then by a Time magazine reporter who interviewed Iraqi survivors.

Army Col. Gregory Watt was assigned to do a quick look. Carrasco, the battalion operations officer, went to Chessani and suggested that the Marine Corps might consider doing its own investigation.

Chessani, who was seated at his desk, whirled around and reacted with uncharacteristic anger. “My men are not murderers!” he shouted. Later he apologized for his outburst, but his view did not change.

In early March, Watt recommended that the Naval Criminal Investigative Service be called in.

‘He loved his Marines’

The NCIS agents took the simple investigative steps that Marines had failed to take: interview Iraqi witnesses, examine bullet holes, review autopsy records and pictures of the bodies. They challenged the accounts of the enlisted Marines who said they had fired the fatal shots in self-defense.

When the battalion returned to Camp Pendleton a month later, Chessani, who had been nominated for a Bronze Star and seemed on track to become a general, was relieved of command along with one of his subordinates, Capt. Lucas M. McConnell, the Kilo Company commander.

In December, the Marine Corps charged Wuterich, Sharratt, Tatum and Dela Cruz with murder. Chessani; McConnell; 1st Lt. Andrew A. Grayson, an intelligence officer; and Capt. Randy W. Stone, a battalion lawyer, were charged with dereliction of duty for not investigating whether a war crime had been committed.

Charges against Dela Cruz were dropped in exchange for his testimony. Article 32 hearings, akin to preliminary hearings, are underway in the remaining cases. In each, a hearing officer will recommend to Lt. Gen. James N. Mattis, commander of Marine Forces Central Command, whether the case should go to court-martial, be dropped or be handled through administrative punishment.

Last month, prosecutors urged that Chessani’s case go to trial to prove that “the Marine Corps can investigate itself.” They allege that Chessani, now 43, had reacted like a father unable to believe his sons could do wrong.

Said Lt. Col. Sean Sullivan, the lead prosecutor: “The battalion commander had such a mind-set that he loved his Marines so much, had so much faith in them, that he could not believe that they could murder civilians.”

--

(BEGIN TEXT OF INFOBOX)

The actions of Marines on Nov. 19, 2005, after an attack on their convoy using an improvised explosive device led to the worst charges of alleged atrocities leveled against U.S. troops during the Iraq war.

Accounts of what happened after the IED exploded vary, but here are the basics:

--

7:15 a.m. Roadside bomb rips apart last in a column of four Humvees, killing one Marine and

wounding two.

--

7:30 a.m. Approaching white Opel is stopped; five men are shot dead by Marines.

--

7:45--8 a.m. Marines search two houses; 15 people killed, including three women and seven children.

--

9:30 a.m. Two other houses searched; in one, four men shot dead.

--

9--11 a.m. Other Marines in gun battle with insurgents that ends with an airstrike.

--

All times approximate

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.