Google and God’s Mind

- Share via

The boogie-woogie Google boys, it appears, dream of taking over the universe by gathering all the “information” in the world and creating the electronic equivalent of, in their own modest words, “the mind of God.” If you are taken in by all the fanfare and hoopla that have attended their project to digitize all the books in a number of major libraries (including the University of Michigan and New York Public), you would think they are well on their way to godliness.

I do not share that opinion. The books in great libraries are much more than the sum of their parts. They are designed to be read sequentially and cumulatively, so that the reader gains knowledge in the reading.

A good scholarly book on, say, prisons in 19th century France goes well beyond simply supplying facts. Just imagine that book digitized and available for Googling. Google isn’t saying exactly how such a search would work, but if it’s anything like the current system, you might enter, say, “Nantes+Prisons” and get back hundreds of thousands of “hits.” Somewhere in those hundreds of thousands would be a reference to a paragraph or more in our book. If you found it, what would you do with it? Supposing it says “ ... there were few murderers in the prisons of Nantes in 1874 ... “ and gives you the source of the paragraph. That is all but useless. Absent a lot more searching, you have no idea whether there are other references to the subject in the book, and the “information” you have found is almost meaningless out of context.

So, you abandon that line of inquiry or resolve to read the book. Are you going to do that online, assuming it’s out of copyright? (In the Google scheme, hundreds of thousands of books in copyright will not be available to be read as a whole.) Not many would choose to stare at a screen long enough to do that.

Are you going to print the book, and end up with 500 unbound sheets? Or will you request the actual book (in copyright or out) through the active and developed interlibrary lending system that supplies thousands of books daily to scholars, researchers and dilettantes worldwide? The latter involves a short wait, of course. We all know that, in Googleworld, speed is of the essence, but it is not to most scholarly research in the real world.

The nub of the matter lies in the distinction between information (data, facts, images, quotes and brief texts that can be used out of context) and recorded knowledge (the cumulative exposition found in scholarly and literary texts and in popular nonfiction). When it comes to information, a snippet from Page 142 might be useful. When it comes to recorded knowledge, a snippet from Page 142 must be understood in the light of pages 1 through 141 or the text was not worth writing and publishing in the first place.

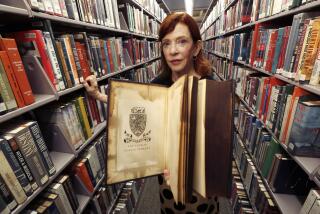

I am all in favor of digitizing books that concentrate on delivering information, such as dictionaries, encyclopedias and gazetteers, as opposed to knowledge. I also favor digitizing such library holdings as unique manuscript collections, or photographs, when seeing the object itself is the point (this is reportedly the deal the New York Public Library has made with Google). I believe, however, that massive databases of digitized whole books, especially scholarly books, are expensive exercises in futility based on the staggering notion that, for the first time in history, one form of communication (electronic) will supplant and obliterate all previous forms.

It is beyond premature to prepare to mourn the death of libraries and the death of the book. If I had shares in publishing companies I would hang on to them. This latest version of Google hype will no doubt join taking personal commuter helicopters to work and carrying the Library of Congress in a briefcase on microfilm as “back to the future” failures, for the simple reason that they were solutions in search of a problem.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.