Let felons vote

- Share via

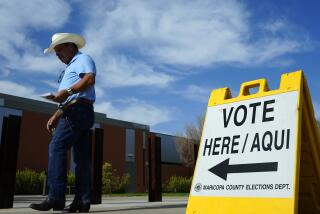

Turnout for Tuesday’s election is expected to be vast, but one group will be grievously underrepresented in many states. As many as 5 million felons are barred from exercising the most important duty of citizenship even though they have served their sentences or been released on parole. A disproportionate number of them are African Americans.

According to the Sentencing Project, 13% of African American males are unable to vote because of felon-disenfranchisement statutes. But even without evidence of racial skewing, laws that prevent felons from voting after they have been released contradict the notion of rehabilitation and send a message to former inmates that they are literally second-class citizens.

As The Times recently reported, several states have eased or eliminated restrictions on voting by former prisoners convicted of felonies. But 12 states permanently prohibit some felons from voting, and 35, including California, bar voting by ex-inmates as long as they are on parole. An argument can be made that this patchwork of protections is an acceptable manifestation of federalism. But state restrictions on felons’ voting rights also affect elections for Congress and for president.

It’s intolerable that a citizen’s ability to help choose the president, the one official who serves the entire nation, depends on whether a particular state decides that a felony conviction requires the revocation of voting rights. Congress could end that inequity by approving the Democracy Restoration Act of 2008. That bill says that a citizen’s right to vote in federal elections “shall not be denied or abridged because that individual has been convicted of a criminal offense unless such individual is serving a felony sentence in a correctional institution or facility at the time of the election.”

The legislation would be limited to federal elections because the Supreme Court has ruled that the states are responsible for determining eligibility to vote in state and local elections. But history suggests that restoring federal voting rights for felons probably would have a ripple effect.

In 1970, the high court ruled that a federal law lowering the voting age to 18 could be applied only to federal elections. The effect of the ruling was to force states to keep two sets of records -- one for federal elections, another for state elections. So burdensome was that system that a constitutional amendment extending the 18-year-old voting age to state elections was quickly ratified by the required 39 states. Even in an age of digital record-keeping, enactment of the Democracy Restoration Act could nudge the states similarly to see the light and allow felons to vote.

Treating offenders who have served their time as criminals for life is cruel and counterproductive. Congress should ensure that in the next presidential election, these disenfranchised Americans will be part of the ultimate exercise in democracy, and not on the outside looking in.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.