Editorial: Here’s hoping Colin Kaepernick’s protest movement can teach schools a lesson in the 1st Amendment

- Share via

It has been 73 years since the Supreme Court ruled that students in public schools couldn’t be forced to pledge allegiance to the American flag or engage in other patriotic demonstrations. But some educators obviously haven’t gotten the message.

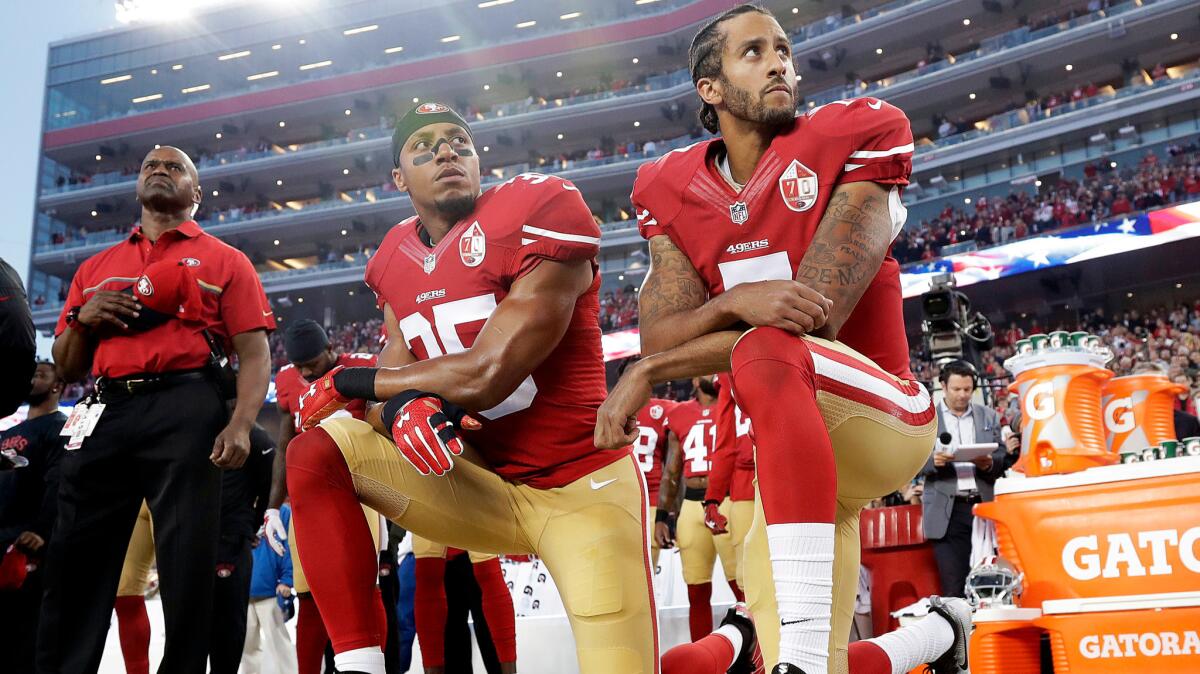

In recent days, a principal in Florida told students they would be ejected from sports events if they didn’t stand during the national anthem. A student in Northern California said her class-participation grade was lowered because she refused to stand during the Pledge of Allegiance, her chosen form of protest over the mistreatment of her Native American ancestors. A high school football player in Massachusetts said he was told he would be suspended if he emulated San Francisco 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick and knelt during the national anthem. In Chicago, a teacher was disciplined for allegedly trying to pull a student out of his seat after he refused to stand for the pledge.

School officials in these cases eventually conceded that students had a right to protest (and the Florida school district said that the principal was reacting not to a protest but to a disturbance at a volleyball game). Still, these episodes are a reminder that many teachers and principals expect students to conform when the school is engaged in a patriotic exercise. The problem is that coerced expressions of patriotism are inconsistent with the 1st Amendment.

As the Supreme Court eloquently explained in its 1943 decision striking down a West Virginia law that required schoolchildren to pledge allegiance to the flag: “If there is any fixed star in our constitutional constellation, it is that no official, high or petty, can prescribe what shall be orthodox in politics, nationalism, religion, or other matters of opinion, or force citizens to confess by word or act their faith therein.”

That decision ought to be included in the training materials for every new teacher and principal. While they’re at it, school districts should also include a 1969 decision in which the court ruled that students in public schools have a constitutional right to express political opinions so long as their speech doesn’t pose a risk of “substantial interference with school discipline or the rights of others.”

A little remedial education in the 1st Amendment for teachers and principals would prevent situations in which students are punished or harassed for exercising their constitutional rights. It might also save school districts some money in legal fees.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion and Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.