Obama has a strategy for fighting ISIS -- one that isn’t working

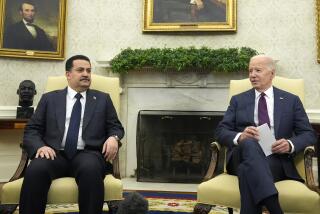

President Obama shakes hands with Iraqi Prime Minister Haider Abadi after a bilateral meeting in the Oval Office on April 14. The two reportedly talked about supporting the fight against ISIS, a strategic partnership and relations in commercial and cultural interests.

- Share via

Obama administration critics often charge that the president has no strategy in the war against Islamic State, but that’s not true.

Eight months ago, after Islamic State’s army swept across northern Iraq, President Obama’s national security aides drew up a plan to reverse the militants’ gains. It began with airstrikes, to stop their advance. It also included a series of steps to enable Iraq to defeat the invaders without using U.S. combat troops.

First, the United States planned to push Nouri Maliki, the stubborn Shiite prime minister, out of office. Then it would help a new government rebuild the country’s security forces, set up a “national guard” of local militia units, and arm Sunni tribesmen who wanted to fight Islamic State. Once those steps were underway, a strengthened Iraqi army would march north and retake Mosul, the country’s second-largest city.

So Obama does have a strategy — but for the most part it hasn’t worked.

U.S. pressure helped shove Maliki out of the prime minister’s office last fall, but his successor, Haider Abadi, hasn’t succeeded in making most of the other changes the administration sought.

Some 3,000 American military advisors are in Iraq, but they couldn’t prevent Iraqi army units from abandoning the western city of Ramadi to Islamic State last week.

Abadi’s government drafted a law to set up the national guard, which would allow Sunni military units to defend Sunni provinces, but Shiite politicians have blocked the bill in parliament.

As for arming the Sunni tribes, U.S. officials say the Iraqi government has budgeted money and weapons for 8,000 fighters in Anbar, the largest Sunni province — but most of the aid hasn’t been delivered. “The weapons have all been approved,” a U.S. official said last week. “We just have to get them to the site and get them to the guys.”

And the Iraqi recapture of Mosul, which some officials rashly predicted could happen this spring? It’s been postponed several times — most recently because aides have concluded that retaking Ramadi must come first.

Obama’s reaction to these reversals has been to counsel patience, reaffirm faith in his strategy — and blame the Iraqis. “If the Iraqis themselves are not willing or capable to arrive at the political accommodations necessary to govern, if they are not willing to fight for the security of their country, we cannot do that for them,” he told Jeffrey Goldberg of the Atlantic magazine last week.

A large portion of the blame clearly does belong in Baghdad — especially to the Shiite factions that have blocked Abadi’s attempts to do more.

But plenty of pro-American Iraqis and Americans who have spent time in the country believe the Obama administration could do more, too — without putting U.S. troops in ground combat.

“America can help,” Rafi Issawi, a moderate Sunni leader and former deputy prime minister, said during a visit to Washington this month. He called on the Obama administration to set up “joint committees” in Sunni provinces to get aid and weapons flowing. “Direct financing from the American side encouraged people to defeat Al Qaeda in 2006 and 2007,” he noted.

“The administration’s strategy is a good strategy — but it only gets done if you actually do it,” Ryan C. Crocker, the former U.S. ambassador in Baghdad, told me. “There hasn’t been enough political engagement at the top level. Where are the visits [to Iraq] by the secretary of State and the secretary of Defense? Where are the phone calls from the president? It’s not happening.”

Crocker said he met with Iraqi politicians in exile last week — “guys who usually want to kill each other” — and heard a common refrain: “Where is America?”

“They’re all realistic; they understand we are not going to do boots on the ground,” he said. “But they all think we can do more than we’re doing now.”

Part of the problem, he warned, is that Abadi is under increasing criticism from both sides, Sunni and Shiite. “He’s being seen as weak — and in Iraq, weakness is death,” he said.

What more could the United States do? There are several options, some already under consideration by the administration, officials say.

The United States could send more advisors and trainers to Iraq to expand the relatively small force already there and allow them to work with more Iraqi units, or even accompany Iraqi forces onto the battlefield.

Although the administration has already increased military aid to the Iraqi army, it could be tougher in demanding that Baghdad’s defense ministry implement its promises to arm Sunni forces before more aid arrives.

The U.S. could also consider arming Sunni forces directly. That step, however, could undermine Abadi and accelerate Iraq’s division into sectarian camps.

Finally, Obama probably needs to take steps to bolster Abadi — which could include more economic aid and even a symbolic visit or two.

If Iraqi attitudes don’t change, the war against Islamic State won’t be won. And Iraqi attitudes don’t appear likely to change without more pressure from the United States — whether it comes from Obama or, 20 months from now, his unlucky successor.

Twitter: @doylemcmanus

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion and Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.