Op-Ed: Who’s minding public pensions?

- Share via

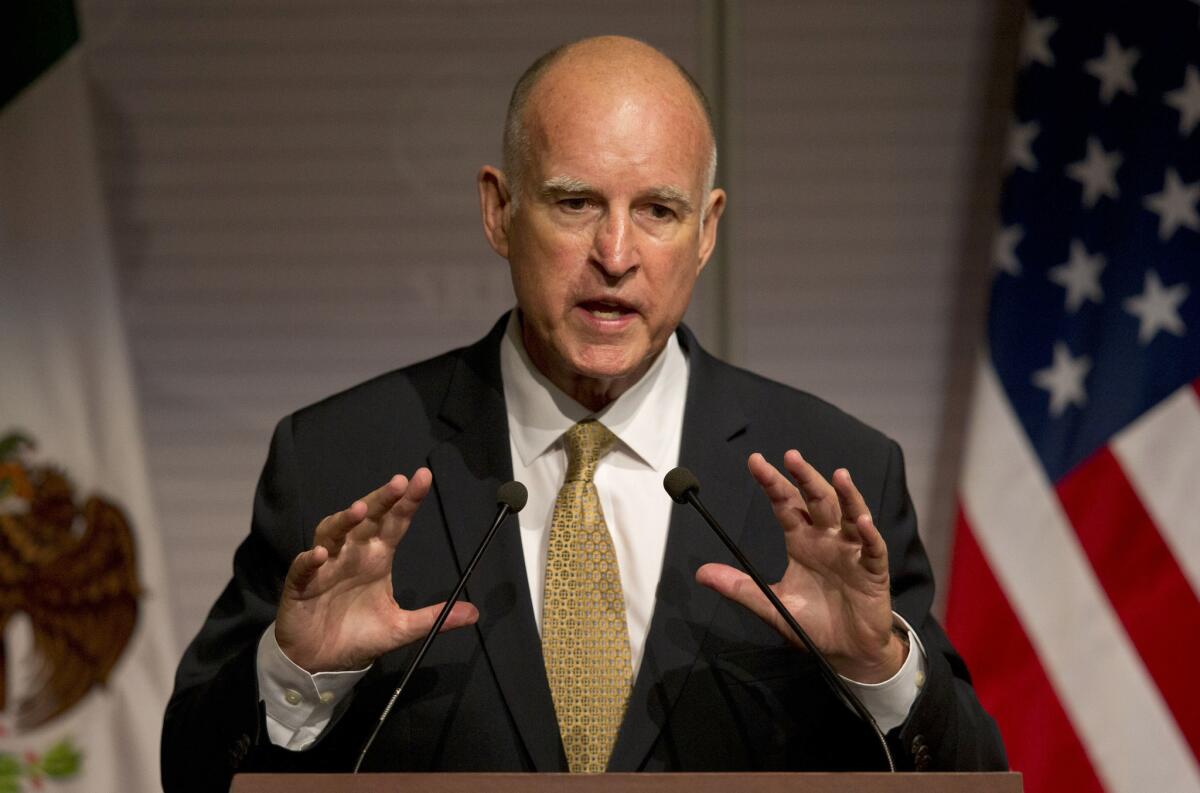

In September 2012, Gov. Jerry Brown signed into law a modest pension reform measure that tried to close some of the loopholes that could inflate pensions. Last week the board of the California Public Employees’ Retirement System, or CalPERS, diluted that legislation by voting to allow temporary pay increases to be figured into pension calculations, thereby raising the amount that some retiring workers can collect. After the vote, Brown declared that the board’s action “undermines the pension reforms enacted just two years ago.”

In 2012, he had attempted to head off just this sort of move with a proposal to expand the board with gubernatorial appointees and thereby reduce the influence of government employees and retirees, who currently hold six of the pension funds’ 13 board seats. The state’s overwhelmingly Democratic legislature refused.

Brown is not alone in his frustration with how public pension funds are run. As officials across the country struggle with underfunded government retirement systems, which have racked up at least $1 trillion in unfunded liability, they are increasingly looking at how the funds are managed. Many public sector pension funds are controlled by boards dominated by public-sector employees and retirees, who are far more likely to look out for the interests of workers than they are for those of taxpayers.

Nearly 60% of government pension funds surveyed in 2010 by the National Assn. of State Retirement Administrators were controlled by boards in which beneficiaries of the pension system — that is, active government workers and retirees — held at least half of all seats. In addition, pension boards often include elected officials who depend heavily on public-sector unions for campaign funds. Is it any wonder, then, that the boards have produced some disastrous results?

The trustees of Detroit’s pension funds, for instance, have been heavily criticized for their role in managing the retirement system as the city spiraled toward bankruptcy. An audit last September of the city’s general pension fund by the restructuring firm Conway MacKenzie targeted the policies of the 10-member board — dominated by five city employees and one retiree — for “effectively robbing” the system of nearly $2 billion in assets through employee-friendly policies, including paying hundreds of millions of dollars in bonus checks to retirees even as Detroit’s fiscal situation deteriorated. The city’s $3.5 billion in unfunded pension debt was a major factor in Detroit emergency manager Kevyn Orr’s decision to file for municipal bankruptcy in July 2013.

Taxpayers in New Orleans pay for a pension system largely managed by current and retired firefighters. Today the troubled Firefighters Pension and Relief Fund has just $85 million in assets, but $424 million in liabilities, thanks to what New Orleans Mayor Mitch Landrieu claims is board mismanagement. Landrieu has balked at making additional payments into the underfunded pension system unless the city gets more seats on the fund’s board. He’s compared the present situation to having to pay the bills for a credit card that someone else controls.

In Houston, the growing cost of firefighters’ pensions has been a particular budget burden, increasing from 13% of payroll in 2003 to 31% last year. But city officials have had to fight for information about the financial situation of the independently run Houston Firefighters Relief and Retirement Fund, created by the state legislature decades ago with a board controlled by five active firefighters and one retiree. Even as the board demanded higher annual contributions from the city, Houston had to go to court to gain access to its books after the trustees refused to turn over the information.

Reformers have sought to change these boards by adding members who would represent the interest of taxpayers. They’ve also tried to move crucial pension system tasks, such as audits and supervision of investment strategy, out of the hands of trustees. But reform has not come easily.

Last year Houston Mayor Annise Parker could not find a single Texas legislator to sponsor a bill that would bring the pension fund of the politically powerful firefighters under city control. Parker has now filed suit to have the legislation governing the pension fund declared unconstitutional because it forces taxpayers to finance a system the city doesn’t run.

Landrieu also tried and failed to get the Louisiana legislature to give the city control over its firefighters’ fund. After a recent audit disclosed that the fund lost half its value between 2010 and 2013, including $15 million lost after it invested in a hedge fund based in the Cayman Islands that went bust, a spokesman for Landrieu sounded grim. “Our only choices are bad and worse,” he said.

Gov. Brown, meanwhile, has instructed his staff to see whether there are ways to “protect the integrity” of the 2012 pension reform legislation in the wake of the CalPERS board’s actions last week. But his options are limited under current law. That’s why it might be time for the governor to renew his efforts to reform and reconstitute the CalPERS board. It’s even possible that, given the board’s recent irresponsible action, the legislature just might go along this time.

Steven Malanga is senior editor of City Journal and a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.