Opinion: What you can learn from Lena Dunham’s rape disclosure

- Share via

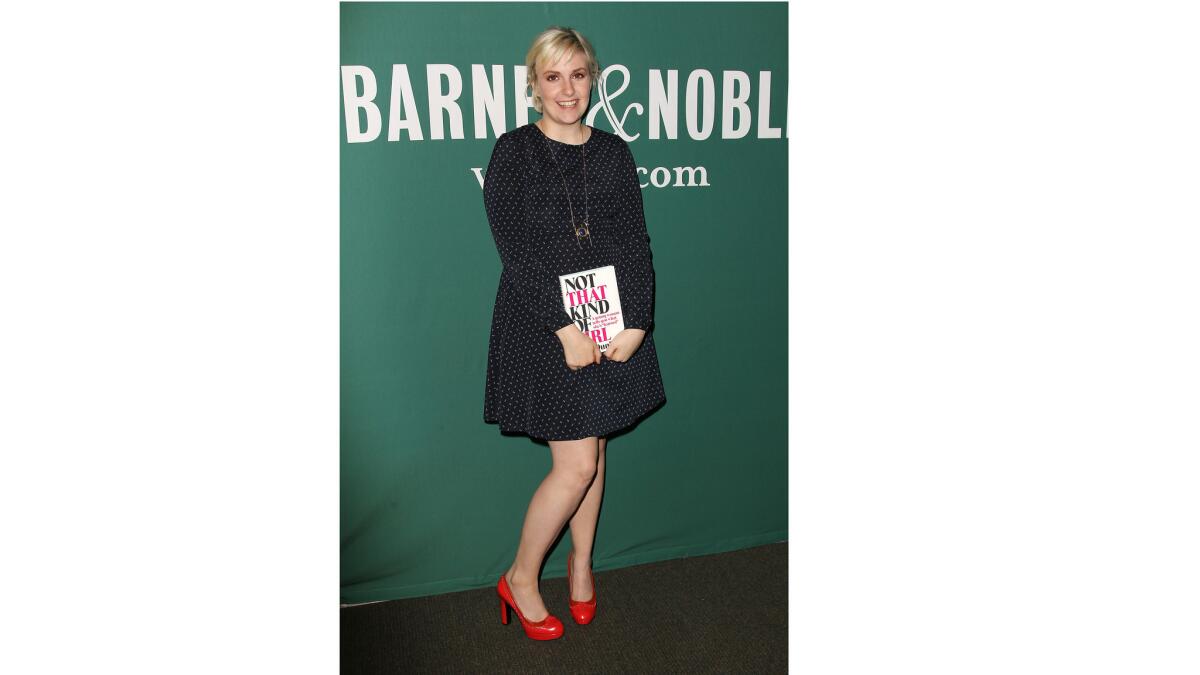

Actress and author Lena Dunham recently disclosed that she was raped during college. In her new book, “Not That Kind of Girl,” Dunham describes her assault and how it took her years to actually call it what it was -- rape. Dunham may have been intoxicated and brought her assailant home, she says, but that doesn’t mean she deserved to be raped: “I feel like there are fifty ways it’s my fault…But I also know that at no moment did I consent to being handled that way.” (You can also hear her candid interview with Terry Gross on “Fresh Air.”)

We’re often fed images of rape featuring a shadowy stranger preying on women in parking lots. But statistically, many victims know their rapist, which can make coming to terms with their assault complicated. Knowing your assailant means that you not only have the chance of facing your rapist regularly in daily life, but that should you disclose, you face serious personal and emotional risk if he is never arrested or prosecuted. Add that to the reality that we live in a culture that is more likely to doubt a rape victim, or the fact that a rapist will likely never spend a night in jail, and it’s no wonder that 60% of rapes go unreported.

“Rape culture,” as Buzzfeed details in its explainer, is a culture where sexual violence is the norm -- in which people aren’t taught not to rape but are taught not to be raped. How do we work toward dismantling the insidious powers of a culture that is built around abusing and violating people and then disbelieving them when they try to come forward?

A good start is California’s recently signed “yes means yes” bill, which requires “affirmative consent” from college students engaged in sexual activity. The law could pave the way for creating a much needed culture of sexual consent. Just last week it was reported that New Hampshire state Rep. Renny Cushing filed a draft of a bill modeled on the California law -- and hopefully more states will follow suit. Talking about what consent means -- and putting policies in place to enforce what it means -- will not by themselves end rape. But hopefully they can be a step toward refocusing a culture that can be confused about what it means to say “yes” to sexual advances.

There is nothing but positivity to gain from a movement that seeks to create dialogue, rather than continue to shroud sex and rape in shame and silence. Billboards, commercials and movies are more sexually graphic than ever, but real discussions about sex -- whether on the meaning of consent or the experiences of pleasure -- remain largely taboo in our society. In 23% of public schools, abstinence-only sex education is still the norm despite research that proves that a comprehensive sex-education curriculum is the most effective way to teach young people about what healthy sex looks like.

There was no conversation about the importance of sexual consent when I was growing up. I had to learn, sometimes the hard way, what did and didn’t feel right to me with my partners. I imagine that most young men growing up today feel the same way and want to know how to be respectful partners. Opening up a dialogue is a small, but important step in gaining that understanding.

Critics like Jonah Goldberg argue that legislating affirmative consent is just another way for liberals to “use the state to impose their morality on others.” But the numbers of sexual assault victims are staggering. According to U.S. Department of Justice, someone is sexually assaulted every two minutes.

Of course there are limits to creating a culture of consent. All too often the onus is put on women to “protect themselves” from being raped (as has been promised by the recently released “rape prevention nail polish”). It’s impossible to think about rape and preventing it out of the context of a culture that continues to blame women for the actions of an assailant. Whether it’s telling them they shouldn’t drink, dress a certain way, or even consort with frat boys, rape prevention still rests largely on the shoulders of the victims.

But now is the time to harness the mainstream awareness around the problem of sexual assault, starting with making sure that we all understand that yes means yes, and no still means no.

Susan Rohwer is a freelance journalist. Follow her on Twitter @susanrohwer.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.