In the heart of the Central Valley, a push to get Latino voters to the polls

- Share via

In a city most known for its prison and farmland, the modest, one-story home of Mary and Raul Gomez has the feel of the quintessential American dream with its trimmed green lawn, little porch and white picket fence. In the driveway, there’s even a remodeled 1968 black Chevrolet Biscayne visible from Dairy Avenue.

For 20 years, it also has served to foster a truly American value — the civic duty of voting — as the campaign headquarters for the Kings County Latino Roundtable. There, in a shaded backyard decked with Oakland Raiders memorabilia, members meet over hot dogs and cold beverages to strategize voter canvassing routes, host candidate meet-and-greets and craft their trusted election guide — logistics for the crucial task of getting Latinos to cast ballots.

“Some think that voting doesn’t matter; it does,” Raul Gomez said as he arranged lawn chairs for Tuesday’s primary night watch party. “Every vote counts. I have seen where people have won by three votes or four votes.”

It could matter a lot this year in the Central Valley and across California, where Democrats are targeting seats long held by Republicans in a national bid to flip the House in November. In many of these congressional contests, low voter turnout has been a perennial hurdle for Democrats, and some campaigns plan to take more active measures to reach residents historically marginalized or shut out of the process.

One key constituency: the Latino voter.

As the fastest-growing electorate, Latinos have vastly reshaped California politics and will hold increasing sway over coming elections as sophisticated voters supporting the candidates who share their values and party affiliation, regardless of heritage. But some political analysts say the population is not meeting its potential, as both parties have failed to connect with the community.

Fernando Guerra, professor and director of the Center for the Study of Los Angeles at Loyola Marymount University, takes a view that’s at once positive and pessimistic.

Early results show this week’s primary brought out a record number of Latino voters compared with similar elections in the past. That Latinos made it onto the November ballot in four statewide races is a fact that should be celebrated, he said.

But “when you compare what occurred to what could have occurred, that is where you struggle with how to improve it,” Guerra said.

Since the 1970s, political analysts have resorted to an overused label to describe the Latino voter bloc: that of “the sleeping giant,” an untapped power that could sway the outcome of an election if only it were awakened.

Latinos now make up California’s single largest ethnic group and 34% of the adult population. Only 18% are likely voters, according to the Public Policy Institute of California. Voter turnout has lagged behind voter registration in every primary and general election since at least 2002, according to the data firm Political Data Inc.

Why these California Republicans keep winning in Democratic-leaning districts »

The 2016 presidential election was supposed to be different. Donald Trump’s call for mass deportations and a border wall was expected to drive Latinos to the polls in higher numbers than before. When those predictions didn’t materialize, voter groups and immigrant rights organizations pledged to try again and focused on increasing Latino voter turnout during this year’s California primary.

The Gomez family has been ahead of it all.

On Tuesday, the couple were on call to pass out voter guides, field last-minute calls for help from voters and give rides to the polls. If there is a so-called sleeping giant, they said, they haven’t seen it.

These leaders organized the Kings County Latino Roundtable because they were fed up with the lack of Latino representation on city and county boards. All were retired, and many had worked in the fields.

Mayor Raymond Lerma, part of that original cohort, remembers that the idea came after a battle with the city to rename a main thoroughfare in Corcoran for human rights activist Cesar Chavez shortly after his death in 1993.

“One City Council member told me, ‘I don’t care if you get 10,000 voters on that petition, I am not going to sign it,’ ” Lerma said. They eventually had a park named in Chavez’s honor, but the group realized that empowering Latino voters could ensure fair access to the polls and increase the ranks of Latinos in leadership at all levels of government.

Mary Gonzales Gomez — like her husband, raised in Corcoran — soon started running for office herself. She has served on local hospital and school boards and is a board member for the Kings County Office of Education.

“Because of the Latino roundtable — that was the force — this is the first time in the history of Corcoran that we have four minorities sitting on City Council,” she said.

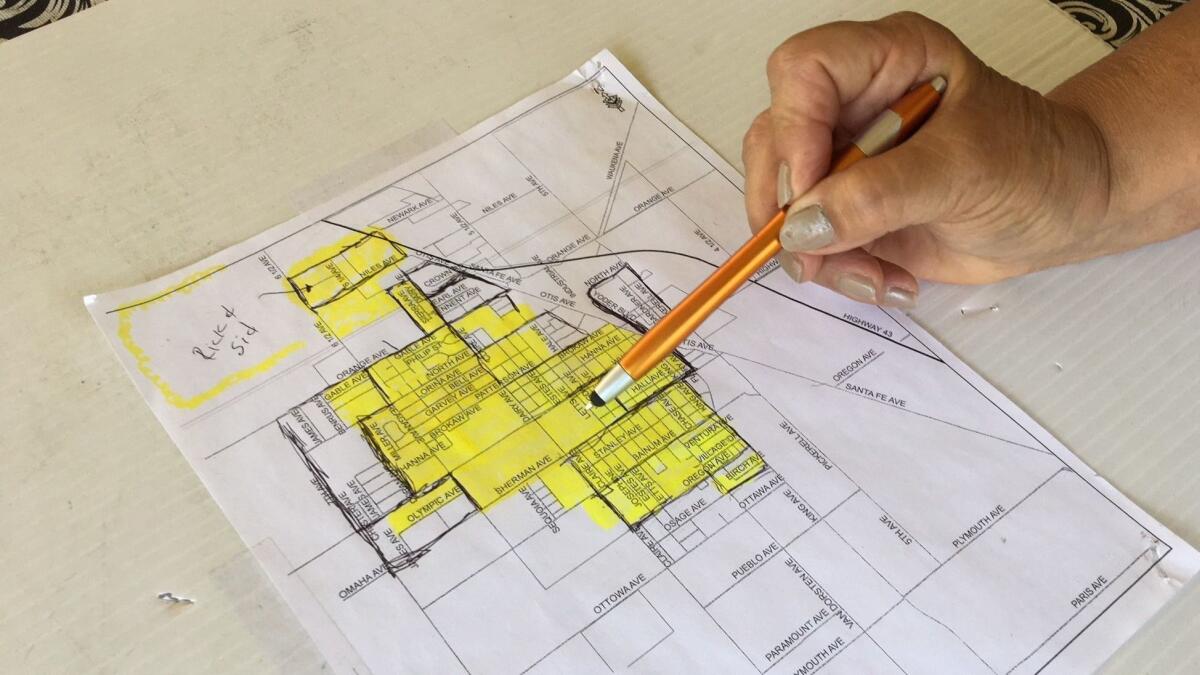

The group now has a core of 12 organizers. They bill it as a Democratic club, though they say their mission is to get all Latinos out to vote regardless of party affiliation. They walk streets and talk to voters, sometimes dodging German shepherds, all throughout Kings County, including nearby Kettleman City and Avenal.

Over the years, they have seen the same struggles with turning out the Latino vote for congressional races. Low levels of education and poverty keep many from the polls. Some are simply uninterested; many others believe their vote won’t make a difference. Or they are confused by the ballot. Or they don’t speak English.

More often, Kings County Latino Roundtable members say, getting out the vote is a lot of work, and national campaigns don’t bother to invest the time in their small cities and counties. Candidates don’t knock on doors or make personal connections.

Jess Garcia said it often feels like outsiders choose their candidates for them. “It’s like we are born Catholic, we live Catholic, we will die Catholic,” he said. “It’s not about questioning the doctrine, and it should be.”

Full coverage of the California primary »

In a year of historically low voter turnout in California, Latinos were hugely underrepresented in the 2014 primary, casting 12% of the votes even though they made up 23% of registered voters. That general trend has held true across the state for years, but perhaps nowhere has the effect been more significant than in the Central Valley, where voter drives and turnout efforts have been sparser than in urban areas such as Los Angeles and San Francisco.

This year, action could pick up as Democrats are running three nationally targeted races against Republicans there in an attempt to recapture the House.

In the 10th District, spanning all of Stanislaus County to the north, Rep. Jeff Denham (R-Turlock) will probably face Democrat Josh Harder in November. Rep. Devin Nunes (R-Tulare) will face Democrat Andrew Janz in the 22nd District, covering Fresno and Tulare counties. And Rep. David Valadao (R-Hanford) will face Democratic businessman TJ Cox in the 21st District, where the Gomezes have focused their efforts.

Some organizations already have been at work: The nonprofit Civica Latino, which has members in Fresno, was created with the ambitious goal of boosting Latino turnout statewide by as many as 700,000 voters for the primary. NextGen America, a progressive nonprofit founded by billionaire Tom Steyer, has been organizing young people in Valadao’s district, where the population is more than 75% Latino.

Ballots are still being counted, and it will be weeks before a clearer picture of turnout emerges in the Central Valley. Latino voter energy in the area seemed absent Tuesday — despite solid Latino candidates in every major state race.

At a primary night party in Fresno for Janz, pop music blasted from speakers and attendees munched on churros. Jim Mendez, a retired physician, blasted Nunes’ track record on immigration, healthcare and taxes but then pointed to the crowd of attendees, many of them white retirees.

Asian and Latino voters represent untapped potential, Mendez said. “This crowd is going to be a problem for [Janz] in November,” he said.

As small as it is, Kings County is a “harbinger for Democrats,” crucial for statewide and national candidates, regardless of their ethnicity, said Mark Martinez, a political science professor at Cal State Bakersfield.

“When you get above 30% of the vote, or in the 40s, you stand good chances of winning,” said Martinez, whose father, Angel, was one of the county’s Latino roundtable founders. “Whether you are running for Assembly, state Senate or Congress, if you don’t crack 40% in Kings, it is not going to happen.”

Yet at the Gomezes, the day went by with few calls from voters and no requests for rides to the polls. They said it was quieter than in previous years, even for an off-year primary.

At a nearby precinct, another Latino roundtable member was working the polls. Anthony Gracian, 31, said many people from his generation don’t believe in voting. One man even registered his frustration by ripping up a voter guide in front of Gracian when he was out knocking on doors.

He keeps at it, Gracian says, telling his friends, “If you don’t vote, you can’t complain.”

Twitter: @jazmineulloa

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.