Athletes’ union movement at Northwestern could have huge implications

- Share via

The news Tuesday that college athletes are seeking representation by a labor union brought a knowing smile to academics who operate far from the field house.

The move by Northwestern football players to join the United Steelworkers union is unprecedented by college athletes, but old news among University of California system graduate student instructors.

“We’ve been there, done that, and it works,” UC Berkeley professor Harley Shaiken said.

Shaiken teaches an undergraduate labor relations course called “The Southern Border,” a class that contains 400 students and eight graduate student instructors. The student instructors are like athletes in that they not only attend school, but also work for the university in a job that produces revenue in the form of tuition.

Yet, unlike the athletes, all eight student teachers belong to a union, which has bargained salaries, benefits and working conditions for all UC system student instructors for more than a decade.

The unionization of college football players can happen because, in a sense, it’s already happened.

“What the Northwestern athletes are doing is an innovative, long-overdue move,” Shaiken said. “It’s not only smart, but possible.”

After years of rhetoric about how the college jocks are wrongfully denied a piece of the billion-dollar pie that is college athletics, labor experts say Tuesday’s announcement is the first real step toward fairness. Are you ready for your favorite letter-sweatered quarterback to start cashing a paycheck? Are you ready for your alma mater’s lovable offensive line to bargain for less practice time?

The big-time college sports world veered onto this groundbreaking course when Ramogi Huma, a former UCLA linebacker and president of the National College Players Assn., filed a petition on behalf of the Northwestern football players with the Chicago office of the National Labor Relations Board.

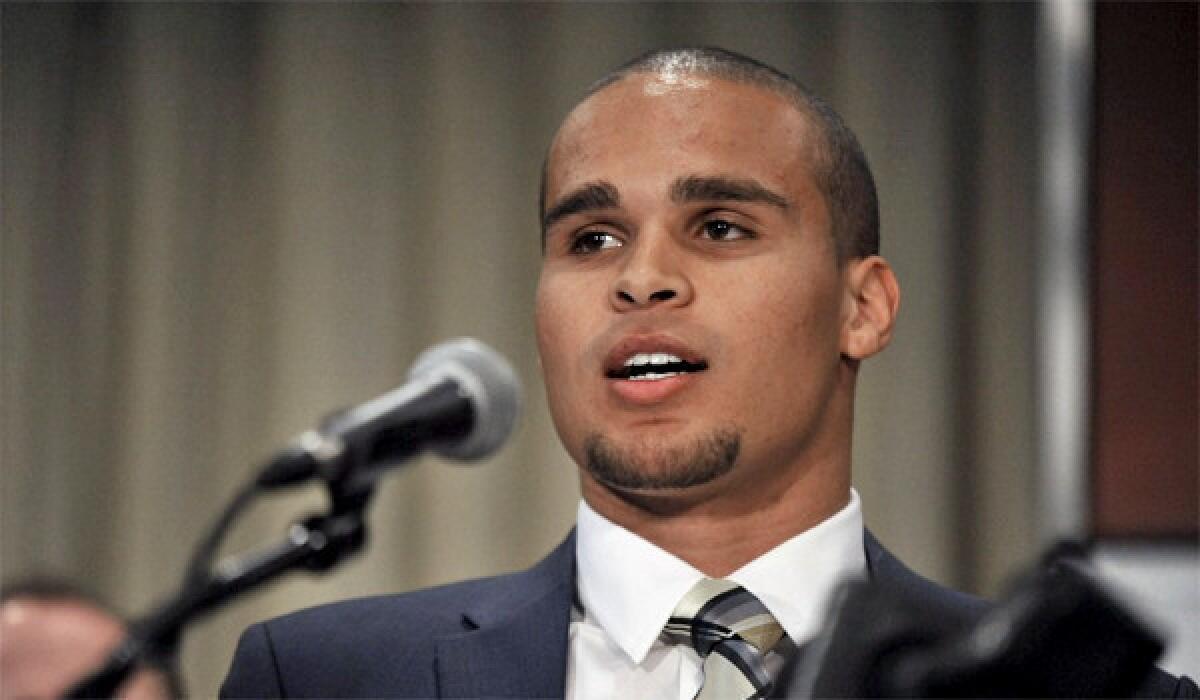

His group is supported by a United Steelworkers union, which was once the home of sports union pioneer Marvin Miller. The face of the movement is former Northwestern quarterback Kain Colter, who is being backed by at least 30% of Northwestern players.

This is not some wristband protest or rhetorical filibuster. This is real. And although labor experts warn that the universities and the NCAA could fight this movement all the way to federal court, the message and mandate are clear enough to hasten change.

“This is high-prestige, high-profile players at a good university saying, ‘Hey, we want to join a union,’” said Nelson Lichtenstein, a UC Santa Barbara history professor and director of the school’s Center for the Study of Work, Labor and Democracy. “This means something.”

The announcement was made at a Chicago news conference during which Huma attacked the NCAA for, among other things, allowing the removal of scholarships from injured players, and lacking a legal obligation to properly protect them from concussions. He didn’t specifically ask for salaries, but that’s coming.

If a student instructor in the UC system can be paid a union-agreed salary of about $8,000 a semester for a 20-hour workweek, what would UCLA quarterback Brett Hundley be worth at a school that receives more than $20 million a year from Pac-12 television fees alone?

“College athletes continue to be subject to unjust and unethical treatment in NCAA sports despite the extraordinary value they bring to their universities,” Huma said at the news conference, adding, “The current model represents a dictatorship.”

At first blush, it’s difficult to understand how the word “dictatorship” can be applied to institutions that provide athletes with tuition, room, board and books in exchange for their athletic services. Any parent who has ever written a five-figure tuition check could certainly dispute the idea that scholarship athletes are not paid.

And certainly, the idea that pampered college jocks require the services of a union is initially laughable. As anyone who has ever been inside USC’s McKay Center can attest, they often work in mini-palaces with benefits — from the best dining halls to the best tutors — that are not available to other students.

“This union-backed attempt to turn student-athletes into employees undermines the purpose of college — an education,” Donald Remy, NCAA chief legal officer, said in a statement.

This columnist has long sided with the opinion that the athletes are paid with that education. But it’s increasingly difficult not to agree with labor experts who say the NCAA is flawed in its reasoning that a student’s experience in college is wholly about receiving an education.

“The response that athletes are just students is a real slight,” Lichtenstein said. “They are clearly also employees. You don’t have to choose. You can be both.”

The NCAA has cowered from the word “employee” after a 1953 Colorado Supreme Court ruling upheld a determination that a University of Denver football player was an “employee” covered by the state’s worker’s compensation law. Thus was born, about a decade later, that ubiquitous phrase, “student-athlete.”

“The universities just want to save money, that’s so clear,” Lichtenstein said. “They pull in millions of dollars and they are happy to get the free labor.”

Lichtenstein taught a graduate class Tuesday called “Colloquium in Labor and Capital.” He estimated that after class, seven of his eight students work as student instructors in other classes, a job for which they have unionized and are paid. He wondered, why should athletes who hurry from class to play football for a college team that brings in millions be treated any differently?

“What happened with the Northwestern college football players speaks directly to what has happened to our student instructors,” said Lichtenstein.

In Berkeley, Shaiken chuckled at the notion that unions could do anything but help college athletes. Of course, there would be no need for a union if universities truly cared only about helping college athletes.

“The union hasn’t limited me at all with my graduate student instructors but, in fact, has made me more aware of their needs,” he said. “Why would the NCAA resist this? What are they so afraid of?”

Twitter: @billplaschke

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.