In Edinburgh, an independent streak

- Share via

Edinburgh, Scotland — IT was 2 p.m. on one of those brooding, rain-soaked winter days when it’s hard to even remember what sunlight looks like.

As I approached the doors of Edinburgh’s new Scottish Parliament building, a crowd was milling around the main entrance, a few dozen were clearing airport-style security checks inside, and several hundred seemed to be hanging around in the building’s cavernous lobby. If bad weather is supposed to keep people at home, someone had forgotten to tell these folks.

The eclectically Modernist complex at the foot of the Royal Mile -- the inclined Edinburgh street between the hilltop castle and the Palace of Holyroodhouse -- was officially opened by a smiling, pink-outfitted Queen Elizabeth II in October 2004. Its matte silver exteriors, bamboo wall features and jigsaw-shaped windows seem a bit odd in an area known more for its ancient stone cottages and 17th century townhouses. (The parliament itself occupies land where a brewery once stood.)

Visiting the building is the Scots’ equivalent of a U.S. citizen’s trip to the Capitol. The site also has become an attraction for overseas visitors interested in history, architecture and grand public buildings. While locals and tourists begin to embrace Edinburgh’s “new castle,” the story of the building’s creation -- like the best Scottish tales -- is fraught with intrigue and controversy.

Scotland had officially ruled its own affairs for almost 100 years when the Act of Union brought the country under English jurisdiction in 1707. The hostile legislation, still reviled by some Scots, marked the end of the nation’s own parliament -- it had been the first one in the British Isles -- and the start of nearly 300 years of largely disinterested rule from London.

But when current British Prime Minister Tony Blair promised a north-of-the-border referendum on devolution, a kind of limited independence, as part of a package of mid-1990s electoral pledges, Scottish pride and the possibility of self-rule were rekindled. The referendum vote in 1997 delivered a resounding “yes” and plans were drawn up for Scotland to begin taking charge of its affairs once more.

As newly elected Members of the Scottish Parliament began meeting in a temporary hall space in Edinburgh, plans were drafted for a grand new building.

The project didn’t go quite according to plan.

A few months after construction started, the media began reporting dramatic inefficiencies and blank-check-type cost overruns. And tragedy dogged the project. Donald Dewar, the Scottish First Minister and the project’s biggest champion, and Enric Miralles, its renowned Spanish architect, died within a few months of each other in 2000.

With half-built, bizarre-looking structures emerging on the site, locals began wondering what was going on, and whispers suggested that the enterprise was jinxed.

But the project limped on, and when the world’s newest parliament eventually opened its doors three years late, with a price tag of about $800 million, thousands lined the streets for a glimpse of the queen, the invited guests and, most of all, the building.

When I visited last December, the tide was turning away from the controversy toward a growing appreciation for the striking features of the new building, now being recognized as one of Britain’s most important contemporary architectural treasures. I joined the jury of visitors passing through the parliament’s doors in its first 12 months.

A striking sight

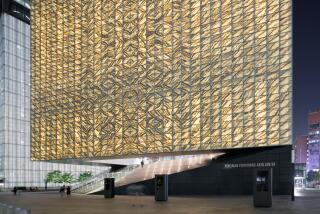

THE building’s frontage is a frankly bizarre combination of bare, curving concrete; nondescript glass doors; and rows of crooked bamboo canes placed above eye level and pointing skyward. They recall Disneyland’s Jungle Cruise ride, but Miralles intended them to symbolize that the building is growing out of the landscape around it. The grassy peaks of Arthur’s Seat and Salisbury Crags loom nearby, and the complex is wedged between these natural surroundings and the bustling cityscape.

After ducking inside out of the rain and clearing security, I headed into the main hall. The low ceiling here is in three barrel-vaulted sections. Small saltire crosses, echoing the Scottish flag, are recessed in the ceiling’s smooth, gray concrete. With sparkling granite and regional Caithness stone covering the floors, which abut oak and sycamore walls, there seemed to be a Scandinavian design aesthetic.

I checked out some of the waist-level display cabinets intended to give historical context to the new parliament. Artifacts included a 2-foot-tall silver and gold sculpture symbolizing the crown, sword and scepter of the Scottish crown jewels and the official document recording the 1997 referendum. This was accompanied by a kind of “modern Scottish politics 101” display showing how committees work and what politicians do. Reflecting the country’s official bilingualism, information panels were in English and Gaelic.

Realizing it was time to join my group for one of the behind-the-scenes public tours that operate throughout the day, I ambled toward a red-blazer-clad woman. She outlined our schedule. With military precision, we would visit a series of usually out-of-bounds areas of the building where photography was prohibited. With a warning to “stick close together to avoid activating security,” we shuffled from the lobby and into a tiny side corridor.

Up a short flight of stairs, we arrived in what’s known as the garden lobby. Without the crowds of the main hall, the quiet was noticeable. We talked in whispers, in deference to our surroundings. Through some picture windows, we could see the parliament’s fledgling garden, with slender young apple trees and trim box hedges, and a wall of irregular windows no two of which were the same. They are the individual offices of the 129 members of parliament.

Our guide launched into the story behind the building, avoiding the controversial issues. We learned that the Barcelona-based architect Miralles was renowned for his civic buildings across Europe, especially in his Spanish homeland, but that the Scottish Parliament was his grandest vision.

Early in the project, he had made clear his determination to reach out to those millions of Scots who had left the country. His initial concept was inspired by the idea of upturned boats resting on the shore after a long voyage home. These shapes form the peaks of the building’s four central towers.

All the buildings that make up the complex have a scattershot feel: Lines are rarely parallel, and potential patterns are often subverted. Our guide said the plan was deliberate: Miralles, in one of his earliest brainstorming sessions, had thrown some leaves and twigs on a piece of paper and said, “That’s the new Scottish Parliament.”

Dozens of original artworks have been placed throughout the complex, although most can be seen only by those who take the tour. I also saw the stunning thorn-shaped ceremonial mace, made of Scottish silver, that was presented to the parliament by Queen Elizabeth before the official opening. It contains an inlaid band of gold, panned from Scottish rivers, that’s intended to symbolize the marriage of parliament, the land and the people.

Stopping briefly to thank our guide and noting that the rain was still streaming down the windows outside, I headed for the gift shop. I strolled over to the T-shirt section for a wearable souvenir. But only children’s sizes remained. Visiting Scots, it seems, want to be seen in the country’s latest fashion: a T-shirt proudly proclaiming “The Scottish Parliament.” It’s been a long time coming.

*

(BEGIN TEXT OF INFOBOX)

Dome, deconstructed

GETTING THERE:

From LAX, connecting service (change of plane) is offered on Lufthansa, KLM, Aer Lingus and British. Restricted round-trip fares begin at $546.

WHERE IT IS:

The Scottish Parliament building is at the eastern end of the Royal Mile, across the street from the entrance to the Palace of Holyroodhouse. It’s a 15-minute walk from the Waverly train station.

TOURS OF PARLIAMENT:

Access to the Scottish Parliament building is free, but there is a charge for guided tours. These take place on Saturdays and Sundays, and on Mondays and Fridays and other weekdays when the parliament is in recess.

Advance booking for guided tours is advised, although this can be done on the day of the visit, subject to availability, at the information desk in the main hall. Tickets are $6.20 for adults; $3.10 for seniors, students and schoolchildren; and free for those 4 and younger. Free gallery tickets are available to those who want to watch parliamentary proceedings in the debating chamber. Debates are held on regular business days from Tuesdays to Thursdays. Booking in advance for these tickets is advised.

TO LEARN MORE:

For more information, call 011-44-131-348-5000 or visit www.scottish.parliament.uk.

-- John Lee

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.