Navigating the labyrinth of life in Fez

- Share via

Fez, Morocco — IN a classroom decked out like a palace in Morocco’s most fervently Islamic city, I learned how to say the four seasons in Arabic.

“And after fasl al-rabia’ [spring] ...” prodded my teacher patiently in classical Arabic, “comes fasl al-saif [summer],” I answered.

“Insha’Allah,” he added, leaning back in his chair and dragging his fingers thoughtfully across the elaborate mosaic tile work that decorated the walls of our classroom at the Arabic Language Institute in Fez.

The teacher’s last utterance -- “If God wills” -- was an affirmation, not an afterthought. Insha’Allah is one of the most ubiquitous phrases in the Arab world. Certainly it was one of the most useful things I learned in the six weeks I spent studying Arabic in Fez. Almost everything here, from plans to meet a friend for coffee to the discussion of major world events, is referred to in terms of Insha’Allah. As we learned in class, even the seasons don’t change without God’s will.

“I’ll be back in time for lunch, Insha’Allah,” I always told my host sister, Fedoua, when I left our home in the medina, the old city, for class each morning. “Insha’Allah,” she echoed, with an expression that at once said she would expect me but allowed for deviation (in the form of a missed bus, a late class, even an unscheduled stop at the Internet cafe, which sidetracked me more than once).

I arrived in Morocco shortly after the official end to the U.S.-led war in Iraq. But with my country still deeply entrenched in both battle and international criticism, I was curious how I would be received in this Muslim land.

Would I be forced to pretend I was Canadian?

No. Nearly all of the Moroccans I met were opposed to the war but drew a clear line between the American government and the American people. My nationality made me a pleasant anomaly. European travelers have long romped in this exotic corner of the continent, but American tourists are still a novelty in Morocco and treated with a special curiosity.

My classes were every weekday morning for four hours; to get to school I walked 15 minutes through the medina before catching a bus for the short ride across town. The campus was in the Ville Nouvelle, the 20th century French protectorate city that lies outside the medina gates. I was surprised to find a little Ivy League of sorts right here at my school in North Africa, complete with penny loafer-wearing coeds. More than 100 students -- mostly Americans and mostly from large universities -- were studying at the Arabic Language Institute for the summer.

There were aspiring spies, recent converts to Islam who yearned to read the Koran and a buffed bunch from the Virginia Military Institute who voiced persistent, unfulfilled requests for McDonald’s.

Why was I there? I had no particular career objectives with the language; I was originally drawn to Arabic for reasons of aesthetics alone. The whorls and curls, dashes and dots are dizzying in their beauty. In Arabic, even a warning label looks worthy of hanging on my wall.

Although the diversity at school made for an unusual learning environment, my home stay was hands down the best thing about studying Arabic.

Many of my classmates found apartments with other Americans in the medina, but I was one of a handful of students who took advantage of the chance to live with a Moroccan family. The school arranges for students to live with families in the Ville Nouvelle or the ancient medina for about $10 a day, which is given to the host family and includes all meals.

The experience was invaluable. Not only did living with the Bouananes, my Moroccan family, give me the chance to speak Arabic most of the time, but it also opened the door for me into a culture not often seen by tourists.

Falling into the slow but steady routine of Moroccan life was the thing I liked best about living in Fez. In the mornings before school, I joined Badr, my host brother, on his shopping trips to the market. “Terry, nimshi ila al-souq?” he called out, letting me know it was time to go.

The medina is a labyrinth of more than 9,600 cobblestone alleys, home to about 250,000 people (a number that’s constantly debated and is probably much higher), with each street devoted to a specific craft or service. Moroccans will tell you that, although such cities as Casablanca and Rabat live in the present, Fez, named to the World Heritage List by UNESCO, lives in the past.

“Dark, fierce and fanatical are those narrow souks of Marrakech,” Edith Wharton wrote in 1919 of Morocco’s other famed Imperial city. And nearly a century later, the same can be said of the serpentine souks (open-air markets) of Fez, where life carries on as it has for more than 1,000 years.

Fez-al-Bali, as the old city is called, is a mind-boggling maze of seamless, dun-colored stucco, enclosed by crumbling ramparts studded with great babs, or doors. Inside the medina walls, pretty and putrid smells swirl -- a mix of “flowers and dead cats” is one author’s description -- and heartwarming and gut-wrenching sights volley for attention in a constant assault on the eyes.

Veiled women carry trays of round dough atop their heads, en route to communal ovens. Kittens cavort atop piles of rotting garbage. And children slide down the slippery streets on crushed plastic soda bottles, shrieking with delight.

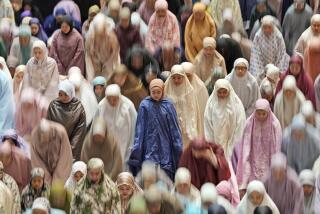

In dark alleys, beggars moan while coins pile up in their outstretched palms. And five times each day, a wail rises from the hundreds of medina mosques, as muezzins call the faithful to pray. Through arching doorways, occasionally visible to the outsider, men press their foreheads to the ground, prostrate in prayer, within the shadowy depths of the mosques.

Narrow, bustling streets

Donkeys, horses and humans are the only traffic able to navigate the narrow, steep streets, and I was thankful to have Badr as my guide.

While Fedoua worked, Badr did the day’s shopping and often helped prepare the various appetizer salads of eggplant, cumin and green peppers that we ate for lunch. When their mother died several years ago and their father fell ill, the siblings took over the duties of the house.

I followed Badr through the throngs of people as loaded baskets brushed against my legs and crowds of people, mostly women, jostled for priority and haggled over the prices at the most popular fruit and vegetable stands. Sweet smells of orange blossom water, verbena and peppermint for Morocco’s national drink, mint tea, wafted on the air, only to be displaced later by the raw odor of skinned goats and defeathered turkeys hanging in the sun.

Badr and I relished a rare shady spot where an old man sold herbs in a coriander-infused pocket of air. Then we reluctantly stepped back out into the harsh sunlight and a swarm of flies to visit vendors selling gray eels.

Badr divided his time between greeting friends and relatives with the four traditional kisses on the cheek and digging into his pockets to find a few dirhams for the beggars who tugged on his sleeves and thrust their hands open wide.

A friend at the language school once told me that if I ever planned to buy anything in Morocco, I would to have to bargain furiously for a fair price. As I watched Badr deal with the vendors, I thought that this appeared to be true for Moroccans too.

Here’s how it usually went when we were shopping for, say, oranges. Badr approached the stand (usually a wheelbarrow with an umbrella over it) with a noncommittal look, as I dropped off into the shadows to avoid adding any possible tourist inflation to the price. He sized up the product, squeezing and smelling a few specimens, then gave the vendor his price.

Lots of eye rolling and huffing and puffing on both sides ensued, until finally a middle ground was reached. The game over, smiles broke out all around. Then we headed off for the potatoes, the neat pyramids of colorful spices or the man selling bags of olive oil soap and started over again.

The chicken man, Mohamed, was our friend, meaning there was no bargaining. We’d just say how many chickens we wanted, then watch Mohamed scurry to pluck a few of the feistier ones off the feather-covered shelf. As dictated by the Koran, Mohamed turned each chicken’s throat east to face Mecca, uttered “bismillah” (in the name of God) and sliced the bird’s throat with a precise flash of the knife. Then it was quickly dunked in hot water, the feathers were pulled off and we were ready to go.

On the way home from the souk, Badr and I chatted about domestic duties, and I asked him if he ever wanted to get married. “Insha’Allah,” he said, telling me that he wanted a family of his own someday, but right now his sister and father needed him.

No woman would marry him anyway, he said with a shrug and his usual smile. “No money, no future,” he said, lamenting that he had no steady job and no foreseeable stability.

Later that morning I was in class, contracting my throat to make a cawing noise and aspirating the letter H as if wheezing for air.

“You will learn to speak Arabic, Insha’Allah; keep trying,” my teacher said encouragingly, expressive eyes imploring hope, jaunty mustache bobbing up and down.

To a native English speaker, the noises don’t come naturally. I’ve studied Dutch, a guttural language. So when we practiced the throat-clearing letters “ghayn” and “kha,” I enjoyed a false confidence.

Then my teacher explained that there’s even an Arabic letter for a catch in the throat called the hamza. He calls it a glottal stop, a sound we apparently make in English (little did I know) but for which we don’t bother assigning a letter. I practice hamza by saying “Uh-oh” over and over.

“ ‘Uh-oh’ is right,” I thought to myself as my teacher, ever the optimist, sent more Insha’Allah encouragement my way.

I persevered, but before long, my classes became secondary in importance to life with the Bouananes.

With all the complex grammar and rules, class was the skeleton, but the daily interactions with my host family were the lifeblood of my time in Fez. On my last night in Morocco, Fedoua taught me to cook bestila -- a pie of pigeon, cinnamon and almonds layered between thin pastry sheets -- the traditional dish of Fez.

We ate at low tables, sweating from the warm food and the dry eastern wind called the sharqi, which blows from the Sahara.

“We will miss you,” Fedoua and Badr said to me.

Abandoning the proper Arabic I learned in school for the Moroccan dialect they taught me at home, I told my host brother and sister that they were welcome in America, sadly acknowledging to myself that the chance of their visiting is very remote. “Insha’Allah,” they said with a smile.

I told them I would return to see them in Fez. It will be in the spring, during the Islamic holiday Aid al-Adha, when the medina streets run red with the blood of sacrificed lambs as Muslims celebrate Abraham’s sacrifice to God. I have learned from Fedoua and Badr that it’s a celebration of generous giving, not unlike Thanksgiving, a time of kept promises and devotion to the poor. A third of the meat from every sacrificed animal is given to the needy.

I want to be there for this important family holiday and, Insha’Allah, I will.

*

(BEGIN TEXT OF INFOBOX)

*

To the medina

GETTING THERE:

From LAX, Air France has connecting service (change of planes) to Casablanca, connecting to Royal Air Maroc to Fez. British, Air New Zealand, Virgin Atlantic, American, United and Swiss airlines have service to London, connecting to Royal Air Maroc to Casablanca and Fez. Restricted round-trip fares begin at $1,271.

TELEPHONES:

To call the numbers below from the U.S., dial 011 (the international dialing code), 212 (country code for Morocco) followed by the area code prefix and the local number.

WHERE TO STAY:

Sofitel Palais Jamai Fes, Bab Guissa 30000, Fez; 55-634331 fax 55-635096, www.sofitel.com. This luxury hotel, built in 1879 in traditional Moorish style, is atop the medina and has the prettiest pool in town. Doubles from $201 with breakfast.

La Maison Bleue, 2 Place de L’Istiqial, Batha 30000, Fez; 55-636-052, fax 55-740-686, www.maisonbleue.com. This inn at the entrance to the medina has beautiful mosaic tile work; antiques grace every room. Doubles from $182, breakfast included.

Hotel Menzeh Zalagh, 10 Rue Mohamed Diouri, Ville Nouvelle, Fez; 55-932-234, fax 55-651-995. Situated in the Ville Nouvelle, this hotel offers basic comforts, with views of the medina from the pool. Live entertainment nightly. Doubles begin at $93.

WHERE TO EAT:

Le Kasbah, Rue Serrajine, Fez, no phone. This laid-back eatery, just inside the medina’s main gates, offers basic Moroccan entrees for $4-$8. A rooftop terrace has great views of the chaotic streets.

Dar Saada, 21 Souq el-Attarine, Fez; 55-637-370. Palace-style restaurant, with mosaic artwork and gurgling fountains, is in the twisting medina alleys. Fassi specialties include bestila and lamb with almonds, $10-$22.

STUDYING ARABIC:

Arabic Language Institute in Fez, B.P. 2136, Fez 30000, Morocco; 55-624-850, fax 55-931-608, www.alif-fes.com. Courses available in modern standard Arabic and colloquial Moroccan Arabic. A six-week session is about $985; three-week courses are $542.

DMG Language School, B.P. 1658, Atlas 30000, Morocco; 55-603-475, www.arabicstudy.com. This German-run school focuses on colloquial Moroccan Arabic, with other courses available. Four-week sessions cost $400. DMG also has a one-day course that includes an introduction to the language and a traditional Moroccan meal for less than $30.

TO LEARN MORE:

Morocco National Tourism Office, 20 E. 46th St., Suite 1201, New York, NY 10017; (212) 557-2520, www.tourismemarocain.ca

-- Terry Ward

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.