Amateur racers get a Formula One thrill

- Share via

LAS VEGAS

Visitors take laps and clock their times at the speedway.

It’s a special moment for every race driver. You tighten the belts, flip down your visor and — quietly, in the privacy of your full-face helmet — say the Shepard’s Prayer. That’s Alan Shepard, the astronaut: “Please, Lord, don’t let me screw up.” Actually, I’m paraphrasing.

Sitting on the pit road at Las Vegas Motor Speedway, cinched into a recently retired Formula One car, I’ve got good reason to be spiritual. This is no ordinary race car — more like a hand grenade with a steering wheel — and a significant driving error here could end in a six-figure pile of carbon fiber. I’m recumbent in the cockpit, with my butt about 2 inches off the pavement. After the technicians check my belts, they install a large foam horse collar around my helmet that locks my head in place. I can see the track; I can see the jet fighters taking off from nearby Nellis Air Force Base; but mostly I see the beer-keg-sized front tires, so soft and sticky that pebbles are embedded in them.

A technician taps me on the helmet. I squeeze the throttle slightly — a row of LED lights winks from a display on the suede-covered steering yoke — and the mechanics start pushing the car for a rolling start. When they yell “GO GO GO,” I drop the clutch. And then: that sound, that awful, wonderful wail that does an ice-water crawl down your spine, that ferocious F1 howl, like a nursery of colicky leaf-blowers — wwwWHAAAAANNGGG!

I believe I speak for my fellow man when I say: Yikes.

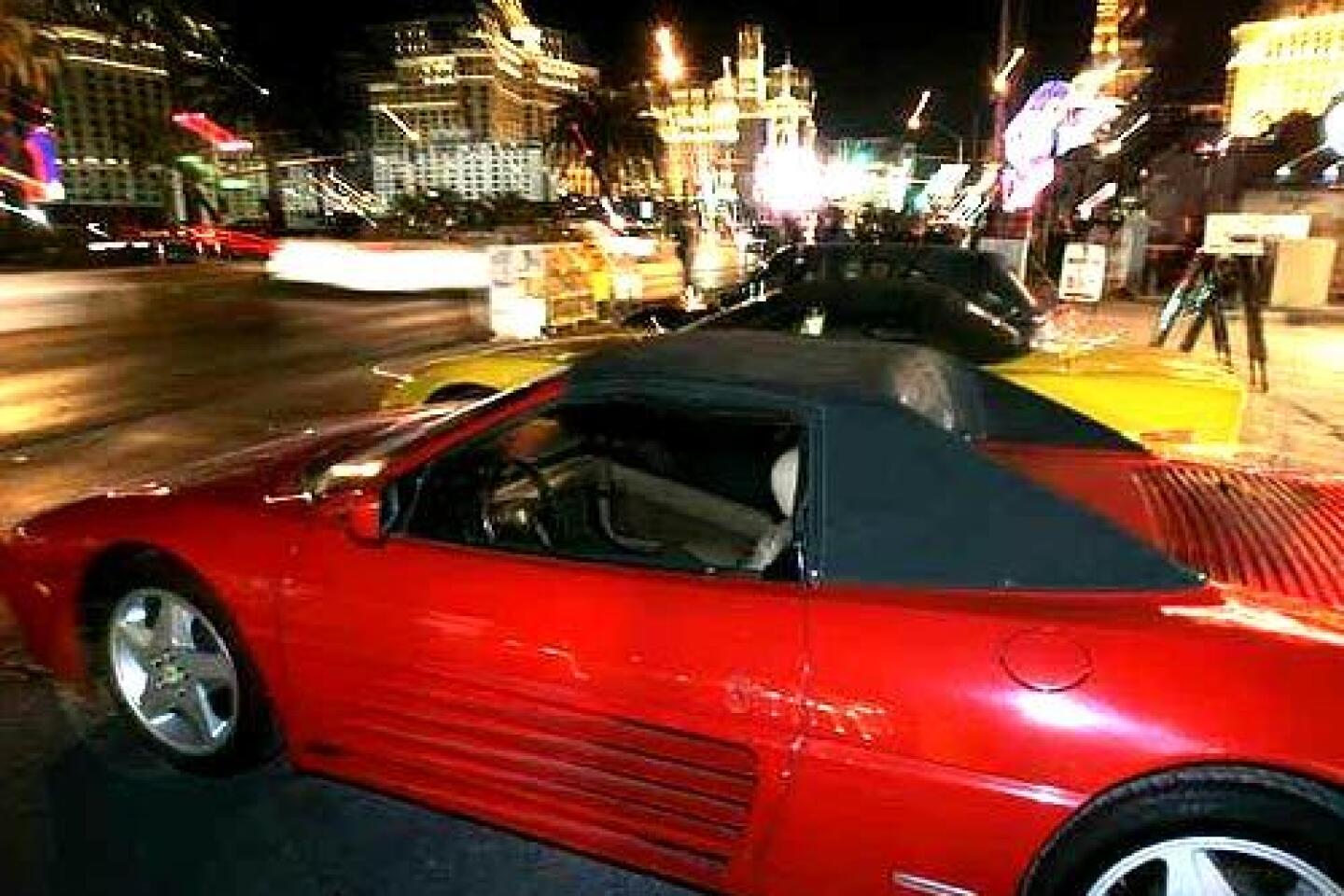

Velocity for rent

Some come to Vegas to visit the town’s fleshpots or to enrich its fleecing parlors, or simply to pass out drunk by the pool. But in a nation obsessed with cars, sex, speed, diversion and the unholy mingling of same, perhaps it’s no surprise that the city of demiurges has become a major destination for people who want to get their wheel freak on.

Here you can rent a Ferrari by the hour, drive a rooster-tailing sand buggy, go roundy-round on the Las Vegas speedway in a 650-horsepower stock car, learn to ride the sickest racing motorcycle the deviants at Honda or Ducati can devise.

At the top of this particular pile of coin-operated thrills, however, is LRS Formula USA, a company that sells mere mortals the chance to wedge, and I do mean wedge, themselves into an honest-to-Odin, full-on F1 car.

“I don’t have little cars,” says LRS principal Pierre-Louis Moroni. “They’re not toys. These are as close to a race-ready F1 car as you can drive, unless you buy one yourself.”

Moroni’s business partner, Laurent Rédon (a former F1 test driver), started LRS Formula Europe four years ago. When Rédon and Moroni partnered to open up a sister operation in the U.S. in 2006, Las Vegas was the natural choice. “The weather is fine most of the year,” Moroni says, “and the clientele is here.”

By that he means rich middle-aged guys looking to check off another item on their lifetime to-do list.

What is a Formula One car, anyway? Briefly, it’s a single-seat, open-wheel car built to the specifications of the FIA (Fédération Internationale de L’Automobile) for competition in grand prix racing, universally regarded as the pinnacle of motor sports.

The cars are stupendous. Here’s the key statistic: With 750 horsepower at the rear wheels and a race-day weight of 1,331 pounds (driver and fluids on board), the typical F1 car has a power-to-weight ratio of 1 horsepower per 1.77 pounds. A Nextel Cup stock car (3,400 pounds) has about the same horsepower, but it’s required to move 2 1/2 times as much mass (1 horsepower per 4.53 pounds). Did somebody call a taxi?

An F1 car can accelerate from 0 to 186 mph and back to 0 in less than 12 seconds. That sound you hear is your cheeks flapping.

In short, F1 cars are amazing machines. They are also unbelievably twitchy and nervous vehicles that tax the superhuman reactions of some of the most elite athletes on Earth. In F1, even great drivers turn into car-killing weenies.

For this reason — and the fact that it costs about $300 per mile to operate them — getting in one of these machines is difficult. I’ve been an automotive journalist for almost 20 years and have begged my way into all sorts of race cars, but an F1 drive has eluded me. Until now.

On a brilliant Friday morning in January at the track, driving instructor John Mefford is briefing his charges about the day’s schedule. After three practice sessions in smaller open-wheel cars (called F2000 cars), we’ll go to lunch and then, “You can get into the big boys,” Mefford says. Clients get a grand total of four laps. “You can actually say you’re one of only about 3,000 people in the world to have driven an F1 car.”

“I haven’t even driven one,” he admits. “It makes me jealous.”

His envy washes over me like winner’s circle Champagne.

At 9:30 a.m., the clients gather for a chalk talk in the trackside tower beside the “south course.” A small breakfast buffet of pastries, juices, coffee and do-it-yourself espresso is set up. On the other side of the room is a pile of blue driver’s suits. LRS Formula USA provides helmets, gloves and shoes. I bring my own fireproof underwear.

The clients — seven men, including me — sit in plastic lawn chairs while Moroni and driving instructor Byron Payne go over the details of the track and F1 cars. It becomes clear pretty early on that Moroni does not, in fact, let complete novices rip around in the world’s most demanding driving machines. Inevitably, and perhaps mercifully, there have been compromises.

First, the car: The two F1 cars on hand — a stunning 2001 ex-Prost team car and a 1996 ex-Arrows car — have been retrofitted with 3.5-liter Cosworth V8 engines. Less fragile and less stressed than the V10s these cars raced with, the Cosworths are still piston-driven volcanoes. Net horsepower is about 680 — ludicrous but substantially less than the 900-plus horsepower these cars had in race trim.

Also, the cars have been fitted with traction control, an electronic driving aid that helps prevent impetuous drivers from accelerating too quickly. Perhaps the single most difficult aspect of driving an F1 car is throttle management. It’s like trying to pour a glass of water from the Hoover Dam.

Also, the car’s first gear has been disconnected. “You’d never be able to get it out of the pits,” Moroni says.

The track: The south road course at the speedway is short (1.5 miles) and tight, with hairpins, switchbacks and other features that keep cars from building up a head of steam. After last season, Moroni blocked a long sweeping right-hander, where a slight miscalculation — or panic attack — could have carbon-splintering consequences. “We had some incidents,” Moroni says.

The final modification is to the drivers: It’s important, says Moroni, to put the fear of God into them. “The F1 cars involve a lot of psychology,” he says. “You’re not going to be an F1 driver. This is just for the experience. So I tell them watch out, it’s a lot of car, be careful. Otherwise people will be all over the track.”

One of my fellow clients is Ryan Ritchie, 32, a physical therapist from Lake Tahoe. Ritchie’s daily ride is an Audi RS4, one of the fastest, best-handling sedans in the world. Once the group gets strapped into the F2000 cars and begins buzzing around the track, it becomes evident to me that I am not quite as quick as Ritchie. The F2000 cars are old, tube-frame cars with four-speed gearboxes. It’s precisely because they are so raw that they are such effective gauges of driving skill. As I watch Ritchie pull away from me, I calculate he’s about a half-second quicker per lap, and that means — on the scales of manly worthiness — he’s half a second better than me.

Later, when he spins out the F1 car in a plume of inglorious desert dust, it will be the highlight of my day.

In the driver’s seat

After a lunch at the Memphis Championship Barbecue restaurant — home of the biggest iced teas in the biggest Mason jars I’ve ever seen — we return to the track to find the F1 cars warmed up and waiting. First to drive the blue ex-Prost car is Dennis Higgs. The 50-year-old has never been in any kind of race car. As the mechanics strap him into the car, he jokes nervously to his friends: “Oh God, what have you guys got me into now?” His eyes are dilated.Moroni coaches him to go easy. “Don’t worry, I’m going to go slow,” Higgs promises, and boy, he means it. Once he gets the car onto the track, he putters around, as if he were driving a carbon-fiber float in the Rose Bowl parade. Moroni rolls his eyes, climbs onto the pit wall and waves at him to go faster. Because the gear selector operates by hydraulic pressure, “he won’t be able to change gears if he doesn’t go faster,” Moroni says.

Higgs pulls into the pits after four of the most leisurely laps imaginable. He pulls off his helmet. He’s laughing and relieved. What was his mental state getting into the car? “I was scared,” he says. “I was too cautious.”

One by one the men climb out of the cars, shaking their heads and smiling unsteadily, seeking reassurance. Moroni congratulates them all with a “Good job!,” a handshake and a pat on the back. Some of them have not done a good job.

Richie, my unbeknownst-to-him rival, spins the car on his first lap and then he spins again a couple of laps later. As the dust flies, I am secretly ecstatic. No matter what else happens today, I won’t be the only driver to “go agricultural.”

Even with his miscues, Richie laps the course with good pace. When he wiggles out of the car, he’s smiling and in a philosophical mood. “I actually thought the Formula [F2000] cars were more fun,” he says, “because you could push them to their limit and make the cars work. With the F1 car, you can’t get anywhere near its limit.

“It’s still a kick in the pants,” Richie says.

Finally, my turn comes in the blue ex-Prost car. With a sucked-in breath, I drop into the recumbent space built for a driver two-thirds my size. Please, Lord, don’t let me, well, you know....

The moment of truth

GO GO GO! ... I drop the clutch. The car bucks and surges. The Cosworth engine lights with a popping bark like an acetylene torch before assuming its open-exhaust bellow.

The track is smooth — smoother than the best subdivision side street — yet I can feel every grain and granule through the super-sensitive steering. I could probably read a newspaper if I ran over it. The car has shocks and dampers, but because they are designed to operate at forces many times those I’m applying, it feels as though it has no suspension at all, just a solid link between my spine and the track.

Yes, I’m driving an F1 car, albeit incredibly slowly. I’m pretty sure I’m going slower than I was in the F2000 car. One reason is that the Bridgestone Potenza tires, the track and the exotic carbon brakes are all stone cold. (It’s about 50 degrees outside.) This is parade lap speed. Once I’m out of sight of the Moroni, I allow myself a little daydream....

“This is incredible. This unknown 47-year-old American, who never sat in a F1 car before last year, has just won the 2008 Grand Prix of Monaco for Scuderia Ferrari. Have you ever seen the like?”

I pump my hand in the air as I’ve seen victorious F1 drivers do when they cross the finish line. Look at him play to the crowds. The tifosi love him!This moment, this brief escapade in grandiose thinking, is LRS Formula USA’s actual product: The brief delusion that somehow, some way, you might actually have been a Formula One driver. For this, the most outsized of professional sports fantasies, Las Vegas is the perfect venue.

I pick my way around the first lap then come back to the main straight. Biting my lip, I squeeze the gas ever so gently. Then ... oh ... my ... God! This hobbled and enfeebled ex-race car — once the pride of international motor sports, now reduced to a pitiable Vegas pony ride — running on cold tires and pump gasoline, fully half the car it used to be, pins me to the seat with a feral, torque-gorging howl. Whoa! Wait! Stop! I’m not ready! The world makes the jump to hyperspace as I grab third and fourth gears. When I get on the brakes for the first corner, the car nose dances around like crazy.

Three more laps. Each lap I get on the gas a little sooner and a little harder. On lap three, approaching the infield hairpin, I wait to brake until the last second, only to discover the carbon brakes are playing hooky. I barely manage to get the car turned. Whew! That was a racy moment.

I am delivered. The flagman waves the checkers and I coast in and kill the engine. My ears are buzzing. I pull off my helmet. Moroni shakes my hand and congratulates me. I’m in a state of babbling, bubbling adrenaline overload. Yeah, deep in my rational brain I know that wasn’t particularly fast — maybe no more than 120 mph at the end of the main straight — but it was dicey, spooky, violent and pure. Four more laps and I think I could have actually gotten something out of the car.

Four more laps. Moroni charges $600 per additional lap. So it’s a $2,400 gamble at a minimum. As ever, the question in Las Vegas is: Do I feel lucky?

dan.neil@latimes.com

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.