Too many travelers find antimalarial regimen hard to swallow

- Share via

EVERY year, about 1,300 people in the United States learn they have malaria. Most are travelers, and many are blase about malaria.

If they had taken antimalarial pills as directed -- before, during and after the trip -- and followed simple precautions, such as using insect repellent, they would have greatly reduced the risk of getting the mosquito-transmitted disease.

Worldwide, malaria affects up to 500 million people a year; a million die of the disease annually. It is endemic in more than 100 countries and territories, according to the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta, including sub-Saharan Africa, South and Central America and Southeast Asia.

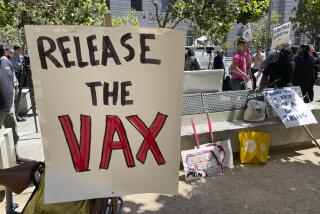

Although efforts are ongoing, experts say development of a commercial vaccine is not imminent -- nor will it be ideal when it arrives. Even then, awareness and taking precautions will be crucial, they say.

Each new report of success with a malaria vaccine raises hopes, but scientists know that developing one is no small task. The life cycle of the malaria parasite is complicated, and the antigens (the proteins found on the organism that trigger the body’s response) are constantly changing, making development of a vaccine difficult.

Infected Anopheles mosquitoes spread malaria by transmitting parasites when they bite humans. The parasites travel to the liver, grow and multiply, and then move on to the red blood cells, multiplying again. The infected blood cells then rupture, spreading the parasites even more.

A malaria vaccine or vaccines, when developed, will probably work best in those who have have been exposed already, says Dr. Bradley Connor, a New York physician specializing in travel medicine.

Connor and other travel medicine doctors advise people to take antimalarial pills if they are visiting areas prone to the disease. Depending on the destination and the drug-resistant strains there, if any, a doctor will typically prescribe one of four types of antimalarials.

But fewer than a third of travelers actually take the antimalarial drugs as prescribed, according to a study of 81 people published in the January issue of the Journal of Travel Medicine.

“You travel to get your mind off daily life,” says Dr. Vincent Lo Re, an infectious disease physician at the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine in Philadelphia. “In the process, travelers are often not thinking about taking pills.” He suggests they take along pillboxes or set alarms reminding them when a dose is due.

He also notes the importance of preventive measures such as using bed netting and insect repellent, preferably with 30% DEET. Wearing long sleeves and pants is recommended, as is limiting outdoor activities from dusk to dawn, when mosquitoes bite.

All returning travelers should pay heed to any flu-like symptoms, says Lo Re.

“If you have gone to a malaria-endemic country and you get sick when you get back, you need to tell your primary care doctor,” he says. And be sure to tell the doctor if you didn’t take the antimalarials as prescribed, he says.

Symptoms of malaria include headache, fatigue, chills, fever, plus nausea and vomiting. Typically, symptoms surface 10 days to a month after infection, but they can occur earlier than that or later -- even a year or longer, according to the CDC.

The CDC posts frequently asked questions about malaria, plus a host of other information about the disease on its website, www.cdc.gov/malaria/faq.htm.

*

Kathleen Doheny can be reached at kathleendohenyearthlink.net.

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.