Brussels terrorist attacks put a heavily Muslim district and Belgium’s police under scrutiny

- Share via

Reporting from BRUSSELS — For months, Salah Abdeslam was Europe’s most-wanted man. He was accused of helping plot the horrific November terrorist attacks carried out by a team of well-organized militants beneath officials’ noses in Paris.

But when Abdeslam was finally captured last week, he wasn’t caught with his alleged Islamic State associates in Syria. He was captured where he grew up, practically in plain sight of his hunters — in Brussels’ working-class, largely Moroccan neighborhood of Molenbeek St. Jean.

Abdeslam’s capture and Tuesday’s bombings of Brussels’ airport and a rail station are already raising questions about the quality of Belgium’s national security, which is seen as weaker than some of its European counterparts.

Live updates: Terrorist attacks in Brussels >>

The latest events are also reinforcing outsiders’ suspicions of Molenbeek as “the jihadi capital of Europe,” or something similar to how Los Angeles viewed Little Tokyo in 1941: a den of dangerous outsiders nestled in the heart of a great and imperiled city.

Molenbeek isn’t a suburb, unlike the teeming banlieues that are home to many Paris immigrant communities. It sits in the heart of Brussels, across a canal from a trendy neighborhood of bars and cafes. A large number of its residents are not newcomers, but native Belgians, many of Moroccan descent, often wearing veils or other traditional clothing.

The Brussels attacks were precipitated by the arrest of a man who was believed to be a mastermind of the Paris attacks in November.

Over the weekend, a customer in a cosmetic store described Molenbeek as “toujours bien, c’est le calm, Zen” — always fine, calm — as others in the shop emphasized that the neighborhood was a place of hard workers who led good lives and stayed out of trouble.

Its image from the outside is more fraught. A French writer recently joked that officials should consider bombing Molenbeek instead of Islamic State’s self-declared capital of Raqqah. Republican presidential candidate Ted Cruz raised the specter of a Molenbeek in the U.S., saying Tuesday that “we need to empower law enforcement to patrol and secure Muslim neighborhoods before they become radicalized.”

Belgium leads European countries with the largest number of fighters per capita leaving to join Islamist militant groups in Syria and Iraq, according to a January report from the International Center for the Study of Radicalization and Political Violence, a London think tank.

Many would-be jihadists have hailed from Molenbeek, including a few of the attackers who killed 129 people in Paris in November.

Molenbeek’s residents have also included Ayoub El Khazzani, a Moroccan national who was subdued by two off-duty U.S. servicemen and other passengers after launching an attack on a train from Amsterdam to Paris last year; Mehdi Nemmouche, who killed three people at a Jewish museum in Brussels in 2014; and several members of a jihadist cell broken up during a police raid in Verviers in eastern Belgium in early 2015.

Molenbeek residents and advocates have complained about being demonized for the actions of a few.

“The trouble is the root causes and not the trees,” said Jamal Ikazban, a deputy in the Brussels Parliament and the leader of the opposition on the Molenbeek Council. He said he worries about Molenbeek becoming “the black sheep of the world.”

“We’re in the same boat,” Ikazban said. “I meet people in Brussels and Molenbeek in tears for what has happened. They are afraid.”

After World War II, Belgium needed workers to help rebuild the country and work in its coal mines, and in the 1960s, Belgium formalized immigration agreements with Morocco and Turkey; many Moroccans settled in Molenbeek.

But several generations later, their descendants have not assimilated — nor have they been welcomed — the way some third- and fourth-generation immigrants often have in other countries. As one third-generation Belgian city bus driver put it, “When I go to Morocco, I am not Moroccan there, and I am not Belgian here.”

High unemployment and disenchantment have helped incubate a generation of restless young men who are drawn to Islamic State’s calls for fighters, experts say. Belgium’s involvement in the U.S.-led military coalition against Islamic State has also made it a target, and experts have wondered whether Belgium’s security forces are up to the task.

Belgium sits at the heart of Europe and hosts the European Union and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, but a linguistic and cultural divide has cleaved the country in half since its birth in 1830, often making national governance difficult. Dutch speakers live in the region of Flanders to the north. French speakers live in Wallonia to the south.

“You’ve obviously got a patchwork and balkanized police structure to begin with, which reflects the broader political picture of the country,” said Frank Cilluffo, director of the Center for Cyber and Homeland Security at George Washington University. “You’ve got a question of political will, a question of capability, a question of capacity.”

Purported Paris attack mastermind Abdelhamid Abaaoud, who hailed from Molenbeek, traveled back and forth between Syria and Belgium, where he claimed God had chosen him “to terrorize the crusaders waging war against the Muslims.” Abaaoud also boasted of buying weapons and setting up a safe house in Belgium.

“All this proves that a Muslim should not fear the bloated image of the crusader intelligence,” Abaaoud said in an interview published in Islamic State’s in-house magazine, Dabiq, in February 2015, about eight months before the attacks on Paris.

“My name and picture were all over the news, yet I was able to stay in their homeland, plan operations against them and leave safely when doing so became necessary,” said Abaaoud, who died in a police raid after the Paris attacks.

Belgian Interior Minister Jan Jambon has complained about the fragmentation of Brussels’ police departments and said agencies have a tendency to hoard information for themselves.

“Brussels is a relatively small city, 1.2 million,” Jambon said at a Politico conference on extremism in November. “And yet we have six police departments. Nineteen different municipalities. New York is a city of [8 million]. How many police departments do they have? One.”

Times staff writer Pearce reported from Los Angeles and special correspondent Chad from Brussels.

Twitter: @MattDPearce

MORE ON BRUSSELS

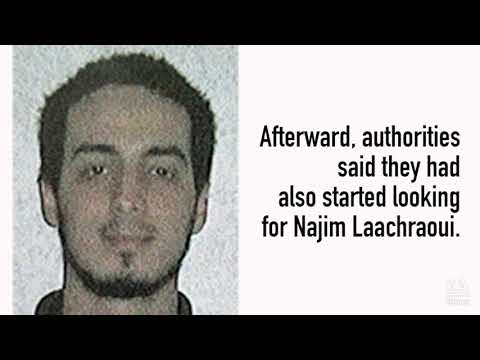

Hunt is on for Brussels bombings suspect; Islamic State warns of more, worse attacks

Middle East countries respond to Brussels attacks with anger and finger-pointing

What we know about the Americans injured in the Brussels attacks

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.