Quality Publishing Still Has a Place in the Electronic Age

- Share via

How many a man has dated a new era in his life from the reading of a book!

--Henry David Thoreau

How right was the sage of Concord. Books can change lives, but, more importantly and universally, books can enrich lives, for to read well-made books is to engage in silent conversation with the best of minds, past and present, and the best of designers and printers. I wonder what Thoreau would say about our era of instant pictures moving and flickering in full color in nearly every home, hypnotizing watchers with images they never dreamed of--like the biblical Romans, Christians and Jews in the television miniseries “A.D.” and state-of-the-art commercial messages.

Would he have despaired over the future of quietly curling up with a good book? Would he have despaired, as many do today, that the book in the age of telecommunications is doomed to extinction?

I suspect not,for Thoreau was a realist, bent on whittling life down to its essentials and seeing it straight on. I think he would have agreed with Sandra Kirshenbaum, publisher of “Fine Print,” a magazine devoted to the arts of fine, limited-edition books.

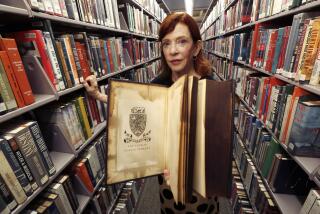

“The beauty of the electronic word is its ephemerality, its speed to materialize and its ability to vaporize at the touch of a button. The book should not, in its future, attempt to compete with that. What the book will have is authority, power, validation. When every office has an inexpensive, type-quality laser printer, and every individual is his own publisher, real printing will be reserved for texts of lasting value,” says Kirshenbaum.

And what is real printing? Is a book printed by offset lithography or laser any less real than a book printed with foundry-cast type? I think not. The element that divides the shabby, quickly printed work and the careful, finely printed one is craftsmanship. It depends on matters of taste, overall design, letter, line and word spacing, choice of type faces and their design, use of color and ornaments and the quality of the paper and of the binding. An “electronic” book can have all these good things, even trade editions, so long as the economics of publishing are not too far out of line with marketplace viability. A shining example of good-quality trade publishing is Dover, which makes the sturdiest and best paperbacks in the business--well designed and executed, and their signatures sewn.

The most noticeable difference between offset and letterpress-printed books is that the ink of the offset book lies on the surface of the paper, while the ink of a letterpress book is “punched” or impressed into the paper’s surface. Of course, offset process color printing has it all over anything letterpress can do.

The impression of the metal type, particularly if printed on dampened, handmade paper, gives an attractive sculpted effect to the page. A finely printed letterpress book can be a pleasure to look at, as well as to read. I’m sure that this is what Kirshenbaum meant by “real” printing.

The melancholy fact is that far too many offset books are poorly designed. Their typography borders on the dreadful, their paper is acidic and deteriorates, and their bindings are of the so-called perfect-bound method, which means the only thing that holds the pages to the spine is glue. After a couple of readings, the book begins to shed pages like autumn leaves.

I have an excellent book on book design, by the noted designer Adrian Wilson, that is falling apart because it was perfect bound.

As a whole, I agree with Kirshenbaum’s assessment of the future of the book. The economics of publishing being what it is (mainly expensive), we’ll probably see only texts of lasting value being awarded craftsmanly care and lasting materials, while the electronic word will serve the instant, short-lived requirements.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.