Opening Day at the Hippodrome : In Moscow, Racing Fans Bet to Win, but Don’t Yell Much

- Share via

MOSCOW — Against all odds, Gorbachev finished last Friday, trailing the field by a wide margin.

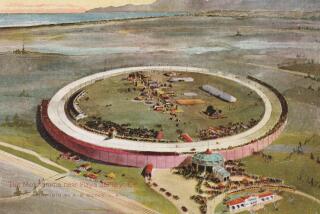

The competition was not, however, in the Politburo at the Kremlin, where Mikhail S. Gorbachev reigns supreme. It was at the Moscow hippodrome, the 150-year-old race track where jockey V. A. Gorbachev (no relation to the Soviet leader) was riding a steed named Iskra, or Spark, the name of a famous revolutionary newspaper edited by V. I. Lenin, founder of the Soviet state.

Hunch players who calculated that Lenin and Gorbachev were a sure thing--especially since the dam’s name was Hierarchy--threw away their rubles on a loser.

It may have symbolized the absence of ideology at the hippodrome, an institution founded by the 19th Century nobility and patronized today largely by the 20th Century proletariat.

Unlike most other public institutions in the Soviet capital, the race track is not adorned with banners praising the Communist Party or urging greater productivity to fulfill the five-year-plan.

Instead, it’s a place where workers can enjoy the spring sunshine and yield to the universal compulsion to try to beat the odds.

A full house--maybe 5,000 people or more--showed up Friday for the opening of the racing season on an 18-race card that began at 1 p.m. and lasted nearly seven hours.

They gambled on Romance, a fickle stallion that ran out of the money, and made Bruise a heavy favorite. Bruise finished sixth.

War songs, celebrating the 40th anniversary of the end of World War II in Europe, blared over the loudspeaker as horseplayers jostled to place their bets, ranging from 50 kopecks (about 58 cents) to a legal maximum of 10 rubles (about $11.50).

In any one race, a bettor supposedly may wager only 60 rubles (about $69), but the ceiling is evaded by bettors who scurry to separate windows to register their bets.

Unlike American race tracks, where new odds are constantly flashed onto tote boards, the Moscow track is barren of such information. Even the program, sold for about 35 cents, contains only limited data on the horses and their past performances. No tip sheets are sold and touts are discouraged.

Unlike their counterparts elsewhere, Soviet horseplayers may be the most subdued in the world.

At Friday’s program, only a lonely few raised their voices to root home their favorites, quite a contrast to American railbirds. Many remain quiet out of fear of drawing the attention of plainclothes security police.

Betting is a complicated process. Only win bets are taken--there’s no place or show action. And payoffs are low--usually two-to-one or three-to-one at most.

But the track also accepts “double” bets on which two horses will finish one-two or two-one. Another combination bet requires horseplayers to pick the winner in three consecutive races. This “triple express” may pay as much as 60 to 1.

One regular at the hippodrome said a typical bettor may drop 20 to 40 rubles in a long day of racing while the regulars, who spend hours squinting at their programs, could win or lose hundreds of rubles in an outing.

Big winners, those who collect 25 rubles or more, are expected to tip the ticket sellers for luck. Big losers pool their funds and split a one ruble ($1.15) bet.

It takes time to collect winnings, with long lines at all payoff windows. On Friday, a gambler who had a winning ticket, waited 15 minutes and pocketed a profit of 50 kopecks (about 58 cents) on a one-ruble bet.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.