A ripple of consequence of the Titanic disaster is that we never hear about ‘unsinkable’ ships anymore

- Share via

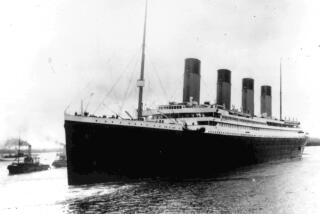

In recalling recently the disastrous maiden voyage of the White Star liner RMS Titanic, I raised a couple of questions about the handling of the supposedly unsinkable ship on that night of April 14, 1912, and left them hanging.

They have been answered by knowledgeable readers, and I feel obliged to pass their answers along.

In the account I gave, which was based on an account in Larry Gouge’s “Old News” paper, Parker’s Gazette, the night was clear and calm, and, though there had been warnings of icebergs, Capt. Edward J. Smith had gone to bed, as had most of the passengers.

“At 11:40 a lookout saw something looming dead ahead. He rang the warning bell three times and called the bridge.

“ ‘What do you see?’ he was asked.

“ ‘Iceberg, dead ahead,’ the lookout shouted.

“ ‘Thank you,’ came the nonchalant reply.

“For some reason First Officer William Murdoch, then on duty, first ordered ‘hard-a-starboard,’ then ‘hard-a-port.’ The ship seemed merely to graze the iceberg as it passed.”

Why did First Officer Murdoch first order “hard-a-starboard” and then “hard-a-port”?

The answer comes from Lt. Cmdr. Robert Irving, USN (ret.), western editor of Sea Heritage News.

“To explain this,” he writes, “it is necessary to understand that the orders to the helm used to be the same orders as to a tiller--the lever on the rudder of a small boat. To make the bow go left, the rudder is moved left--but the tiller goes right. With the old command ‘hard-a-starboard’ the rudder would be driven full left, the stern of the ship would be pushed right, and the axis of the ship would swing to the left. (The modern command is ‘left full rudder.’)

“This would swing the bow of the ship away from the iceberg, which had been ‘dead ahead’ (directly in front of the bow), but the stern would still be moving toward the iceberg.

“The command ‘hard-a-port’ would swing the rudder full right, and the stern would now be pushed left.

“Had the First Officer initiated this sequence a few hundred feet earlier, the Titanic could have ‘zigged’ around the iceberg without harm. As it was, the underbody of the berg--which usually extends beyond the exposed portion--sliced along the forward part of the hull like a can opener. . . .”

Having been warned of icebergs, why didn’t Capt. Smith alter his course and speed?

It was “unbounded hubris and ruthless greed,” says Victor Rosen, who did extensive research into the disaster some years ago.

The White Star liner Titanic was built to wrest the Atlantic speed record from Cunard’s Mauretania. The rivalry between those two lines and other lines in the Atlantic traffic was intense.

“Against that background of unbridled competition and inordinate hubris,” Rosen says, “combined with the lust for greater profits and prestige, the Titanic set sail.

“Sir Bruce Ismay, chairman of White Star, and his fellow directors were determined to wrest the speed record from Cunard at all costs. The company boastfully challenged the gods by proclaiming far and wide that the ship was ‘unsinkable.’ ”

Ismay was aboard the doomed ship. On the morning of April 14 Capt. Smith showed him a wireless message warning of icebergs and said he would change course toward the south and reduce speed. Ismay reminded him of White Star’s mission and told him not to change. Though Smith was captain and could overrule the chairman, he did not.

Ismay, by the way, managed to sneak into one of the overcrowded lifeboats (some say in a woman’s clothing) and landed safely in Ireland, “where he lived out his days in a small village in obscurity, dishonor and disgrace.”

Why did the Titanic have lifeboats for only half her crew and passengers? Again, it was White Star’s cupidity, according to Cmdr. Irving. “There are drawings of the Titanic showing three times the actual number of lifeboats, but the designers’ recommendations were overruled by the owners, since the extra boats involved more cost and less deck room for the passengers’ comfort topside.”

As for why there were no lifeboat drills, he points out: “If you thought your ship was unsinkable, and knew that you had lifeboats for only one-half of the passengers and crew on board, would you hold lifeboat drills? Besides, the policy of the White Star Line was to provide the utmost in comfort for their passengers, and standing out on deck just south of Greenland or Iceland in a life jacket in April is damned uncomfortable.”

Victor Rosen, by the way, doubts the story that Capt. Smith swam a child to a lifeboat then swam back to his ship to go down with it. “Nowhere in any accounts I read did I find any such incredible story. I just don’t believe it.”

Neither do I.

Finally, Timothy L. Smith of Ontario seeks to amend my observation that, like the crash of airliners, the sinking of the Titanic was “only a momentary setback in this technological century.”

“The ripples from the Titanic still flow outward,” he says. “No passenger ship now sails without 100% lifeboat to passenger capacity. There is a permanent ice watch in the North Atlantic. Radios aboard ships at sea are now on 24-hour watch. Steerage passengers are no longer locked below decks. And of course, no one ever claims that his ship is ‘unsinkable.’

“All of these things are a direct result of the Titanic disaster. That vessel on the bottom is a permanent reminder of the fallibility of the human species and the tragic consequences of unfounded faith.”

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.