The Patriots Come of Age at Long Last

- Share via

Old Patriots never die, they just soldier on under other flags, as does Mike Haynes, a present-day Raider who will be reunited with his once-beloved team Sunday in a non-love match called the AFC playoffs.

There was a time when converting New England Patriots into expatriates seemed to be the franchise’s primary business. No exemption was made for stars like Haynes, Russ Francis and Leon Gray. They went in the great migration of 1979-83 and subsequently helped account for two Super Bowl rings and six Pro Bowl appearances.

Lots of talent remained and more was brought in, the Patriots having acquired the No. 1 overall picks in the 1982 and ’84 drafts. They got Texas’ Ken Sims and Nebraska’s Irving Fryar, respectively. They started the season with 12 No. 1s, not to mention the monsters they plucked in lower rounds, like the second, where they got Iowa’s Andre Tippett.

They have nine No. 2s and eight No. 3s, making this Blue-Chip City. The Patriots like to think of themselves as little-respected dark horses, but given the quality of horses on hand, it shouldn’t come as a surprise they’re in the playoffs.

The question is what kept them?

The answer isn’t hard to find, either.

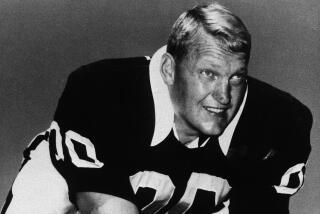

Haynes jumps on the scale in the Raider locker room at El Segundo. It shows 190 pounds, making him a big cornerback, indeed.

He is, in fact, still the reigning king of the corners at 6-2 and 190, with those same long arms that have been knocking down passes for a decade. He’s been All-Pro eight times, missing only two seasons, the one in which he suffered a collapsed lung and the one in which he left the Patriots and signed with the Raiders as a free agent.

“There was a lot of talent there,” Haynes says. “I don’t think you could say they had great teams, but there was a lot of talent. You could say they had the makings of great teams.

“When I came here, everybody asked me, ‘What’s going on there?’ All the thinking around the league was that the Patriots always had the most talent. They always had good drafts.

“It was just the way things were run. You look at the Raiders’ success. From the top of the organization to the bottom, they all want the same thing. Al Davis wants to win.

“But when you’re in a situation where you’re trading two All-Pro players like Russ Francis and Leon Gray, people of that caliber, you start to doubt how dedicated management is to winning.”

Where did it start?

How about the 1976 Oakland-New England meeting in the AFC divisional playoffs, when Ken Stabler hobbled across the goal on a one-yard keeper with 10 seconds left for a 24-21 victory?

“Chuck Fairbanks was the coach then,” Haynes said. “In ‘75, they’d had a lousy year, but in the draft they got Tim Fox, Pete Brock and myself on the first round. In ‘76, we had a great season. We were the only team to beat the Raiders (48-17, at Foxboro), but then they beat us in the playoffs, on a bad call, we felt.

“It was the last drive. They called roughing the quarterback on Ray Hamilton. He had his hand up around Stabler’s face mask. What did the films show? It was a terrible call.”

Said Howie Long, walking by: “It was a good call. I saw it.”

Long was a 16-year-old Boston schoolboy that day, but who knows?

Haynes said: “It gave the Raiders a first down (Stabler had just thrown an incompletion on third and 18 when the flag was thrown). Defensively, we lost our composure after that. We had a lot of guys who wanted to fight.

“Stabler ran the ball in. He wasn’t a young guy anymore but he just followed his blocker, Gene Upshaw, into the end zone. Where was I? I was the guy Gene blocked.

“If it hadn’t been for that call, the Patriots would have been in the Super Bowl.”

If, of course, they had beaten the Steelers in the AFC title game. Instead, the Raiders did and then went on to defeat the Minnesota Vikings in Super Bowl XI. The way Minnesota performed, the Patriots might well have beaten the Vikings.

And many things might not have happened in Massachusetts.

Management was William H. (Billy) Sullivan, a former PR man for Boston College and the old Boston Braves. In 1959, he was a rising business executive who put together a group of investors and became a charter owner in the American Football League.

He was what you might call a firm believer in fiscal responsibility. Somewhere in the middle of his second decade as chief Patriot, this became a recurring issue.

“There was always a lot of unrest over several issues,” the Boston Globe’s Will McDonough said. “Until recently, the players always felt underpaid, that ownership was cheap. A lot of times, the players liked the coach, like Fairbanks, but they didn’t like ownership.”

Unrest took many forms, among them:

--Holdouts. Many of the discontented were clients of Howard Slusher, the ultra-hardballer. But the Patriots didn’t do well with some other agents, either.

Sam Cunningham sat out a season, as did Francis several years later. Gray was holding out with John Hannah when management split them neatly in half, by trading Gray to Houston, where he was All-Pro for the next three seasons.

Haynes said: “When they traded Leon Gray, John Hannah just had a fit. They had some young guys who were just starting to become a force as an offensive line. John went berserk. He said some unkind things to Billy Sullivan.

“Right away, you’re in training camp and guys start wondering, is anybody secure in his job? Just because you’re an All-Pro, does that mean anything?”

--Coaching changes. Fairbanks, coach-general manager, the last Patriot strongman, met with Slusher to end the Hannah-Gray walkout. They reached an agreement that was then reportedly canceled by another of Billy Sullivan’s sons, Chuck, then the son in charge.

Fairbanks later said that was the beginning of the end for him in New England. When word leaked that he was going to Colorado before the last regular-season game in ‘78, Billy Sullivan relieved him on the spot. That was the famous Monday night game in Miami when the Patriots were co-coached by Ron Erhardt and Hank Bullough.

Two weeks later, they made a brief playoff appearance at Houston and lost, 31-17.

--Needling. In the season in which Haynes missed games with the collapsed lung, Billy Sullivan was heard in the lobby of the team’s offices, making a joke about Haynes’ not wanting to play hurt because he was a Slusher guy. Sullivan and Haynes had a postseason meeting to straighten things out.

Haynes said: “I know for a fact I didn’t have a good relationship with Billy. The way I came to the Raiders, with the court fight, there were a lot of things said that were unfortunate. Some things that were said, I’m sure he’d like to forget. Some that were said, I’d like to forget.”

Two years ago, Billy Sullivan moved his then 31-year-old son, Patrick, to general manager. Patrick was more attuned to paying market prices and now the Patriot payroll is among the NFL’s top five.

Fortunately for the Patriots, they had an ace personnel department, headed by former Ram Dick Steinberg. The traded stars became high draft picks and stars of the future, even if with some, like Sims, the future took its sweet time in arriving.

Erhardt lasted for three years as coach. His successor, Ron Meyer, lasted two and was then fired after a 5-3 start in 1984.

Raymond Berry, an Erhardt-Fairbanks assistant who’d been fired in the last mass housecleaning, was brought back.

If this sounded more like musical chairs than intelligent management, things were also coming together. For the first time in recent Patriot history, the owner, general manager, coach and players weren’t at odds over anything. That might not have been everything, but it was a start.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.