The World of Time Inc., : <i> Volume Three, 1961-1980by Curtis Prendergast with Geoffrey Colvin;edited by Robert Lubar (Atheneum: $25; 704 pp.)</i> : <i> The Fanciest Dive by Christopher Byron (Norton: $16.95; 280 pp.)</i>

- Share via

Robert T. Elson, who wrote Volumes One (1923-1941) and Two (1941-1960) of the official corporate history of Time Inc., quite clearly had the livelier time. Across his pages strode the controversial and charismatic figure of Henry Robinson Luce, the intense and beetle-browed co-founder of the enterprise, who was its single and singular proprietor from the early death of his founding partner Briton Hadden in 1929 until his own death in 1967.

Even in retirement in Phoenix (after an undisclosed heart attack), Luce had remained a force in the corporation, commuting to New York, addressing the troops at lunches and dinners, consulting with the great, firing off memos to the leadership he had chosen to succeed him, including Hedley Donovan, who became editor of all the publications.

But Luce, whose Time, Fortune, Life and People have influenced other forms of journalism as well as the magazines’ readers, fades very quickly from Volume Three, written by Curt Prendergast, a veteran Time foreign correspondent, and Geoffrey Colvin, a Fortune editor, in succession to the retired Elson. And, like Disney after Walt or Metro after Mayer, the old place is never quite the same; profitable perhaps, as Time Inc. has remained (despite some whopping bungles), but never so lively or interesting. Collective leadership makes flatter reading, and, inevitably, Volume Three in its last sections is a chronicle of unfamiliar names moving up, and off, the corporate ladder.

(Elson, it is also clear, had the additional advantage of being able to write in the past tense by anywhere from 40 years to a decade at least. Prendergast’s principals are mostly still in place and not insensitive.)

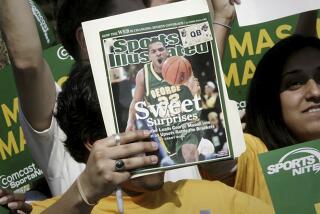

It has at that been an eventful two decades for the corporation. Life, which had been the most prosperous weekly in history, died of television and postal rates, although it was to be reborn as a monthly. Sports Illustrated paid off after years and millions of dollars of losses. Discover, Money and People were born, the latter becoming an item of popular culture (read but not universally admired) in something of the way the young Life had been. But success, power and glory were not inevitable, as they had sometimes seemed when HRL was enunciating the American Century.

Time Inc. became a major operator of pay television systems and, through its Home Box Office and Cinemax operations, a significant maker and distributor of pay television programming. It had got into forest products and suburban weeklies.

The new book’s subtitle has been changed, appropriately. The first volumes were “The Intimate History of a Publishing Enterprise.” This one is “The Intimate History of a Changing Enterprise.” The house that Luce, and print, had built became a conglomerate, with occasionally disastrous consequences, which Volume Three does not minimize but which somehow lose something of their sting in the soothing, annual report prose.

The Washington Star, bought by Time in 1978, sank three years later amid staff bitterness and recriminations, with a net loss before taxes of more than $80 million ($35 million after taxes). Richard Munro, Time Inc.’s chief executive officer, admitted that the corporation had been “naive or unrealistic enough” to think it could make the paper work, and he added that there was a bit of arrogance in there, too.

The book devotes a chapter to the Star debacle, but no more than a page to the even more costly catastrophe of “TV-Cable Week,” the company’s vast and unrealistic scheme to publish and sell a customized weekly cable listings guide to cable systems, which would in turn sell it to their subscribers.

It’s a tale of corporate, bureaucratic non-communication and ineptitude that recalls the making of “Heaven’s Gate,” and it has been told in astonishing detail by Christopher Byron, a former Time reporter and business section writer. Byron, who was a senior editor at “TV-Cable Week,” thus had a close-up view of the dream (of a magazine of Time quality) which became a nightmare venture that was never test-marketed, let alone deeply researched, was never realistically cost-calculated, and never understood to be mechanically impossible of fulfillment, given the computerware then available.

The largest irony was that Time Inc.’s own cable holding company, ATC (American Television & Communications) refused to buy the magazines for its systems: a case of the right hand not lifting to keep the left from withering away.

The magazine lasted less than a half-year in 1983, and died unseen by the vast majority of Americans. Munro is quoted again: “We misjudged the market,” an understatement worthy of George Custer.

The write-off was $47 million, a figure coincidentally in the ballpark with the $44 million “Heaven’s Gate” cost United Artists. And “The Fanciest Dive” (the title is from a poem by Shel Silverstein about a lady who notes too late there is no water in the pool) is the most telling and appalling chronicle of mismanagement since “Final Cut,”Stephen Bach’s memento mori of “Heaven’s Gate.”

Byron writes (from the anger of his own experience) an indicting epilogue about what he calls Time Inc.’s “decade and a half of corporate drift,” in which the Luce-less corporation got into fields far removed “from the cultural premises upon which the corporation rested.”

Chief among the premises was something Luce insisted upon and that was to be known at Time as the separation of church and state-the independence of editorial from advertising. “TV-Cable Week,” Byron says, was the final fruit of conglomerate drift, “a confused effort . . . to bring to market a publication that sought to unite the two separate worlds of church and state, of Mammon and art.”

Prendergast & Co. do not look away from the troubles in “The World of Time, Inc.” The book is candid about the rising discontents over salaries, working conditions and employment practices toward women and minorities that produced a divisive strike in 1976. Although it was settled on management’s original contract offer, the strike declared the sharp change from the confident editorial esprit of Luce days, and it led to some improvements in minority hiring and advancement. (Women are now the managing editors of both Life and People.)

The popularity and verve of its magazines made Time Inc. look like a special phenomenon in American business life. But by now its corporate history reads like many another corporate history its magazines have told, notably in the noisy shifting of gears from the reign of the founding entrepreneur to the era of the professional managers. It is a story reproducible in steel, cars and movies.

Times change and Time changes (more signatures and thoughtful essays, less arrogant omniscience). The company prospers (revenues in the $3 billion range, placement in the top quarter of its own Fortune 500).

An editor-in-chief, currently Henry Anatole Grunwald, is intended to be the editorial conscience of the magazines, but he, too, by definition is a professional manager, with only the weight of tradition to arm him against the state (if he is to be seen as the lonely figure in the church pulpit). The magazines, indeed, are only one of the things the corporation does. And the book concludes with a ringing note to shareholders from CEO Munro that profitable growth under the twin umbrellas of entertainment and information is the name of the game.

Luce, a devout and idealistic free enterpriser, would hardly disagree, but it is impossible not to feel that he would find the conversations around the board table less interesting than they used to be.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.