Workers Now View Borman as Fallen Hero

- Share via

MIAMI — There’s an adage that Frank Borman likes to repeat. “Capitalism without bankruptcy,” he says, “is like Christianity without hell.”

For three years, Eastern Airlines has scampered a step ahead of bankruptcy. And for the same years, its employees have said the company’s leader is taking them to hell in a hand basket.

That basket, the workers complain, has been filled with labor concessions--lower wages and longer hours. The contents, most add angrily, have been frittered away by the boss.

Monday’s frenzied, pre-dawn agreement to sell Eastern to Texas Air Corp. was Borman’s final alternative to bankruptcy. But it represents more than the proposed transfer of ownership of the nation’s third-largest air carrier.

Astronaut to Executive

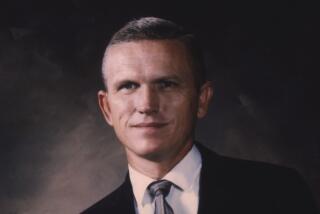

It also is a sad chapter in one of America’s favorite success stories, the heroic astronaut who changed from the nylon and plastic of a space suit to the gray flannel of the corporate board room.

Frank Borman, now 57, once read Genesis to the nation from a space capsule on Christmas Eve. Soon, so goes the scuttlebutt, he is expected to read his resignation as Eastern’s chairman. If so, he would leave as an unpopular man.

“His going to space doesn’t mean anything to us anymore,” said Jim Bechtold, an Eastern mechanic for the past 16 years. “The guy has worn out his welcome.”

And welcome he once surely was. In 1975, when Borman took over Eastern, the airline was on its way to an annual loss of $50 million.

Though the ex-astronaut had been with the company only five years--and had taken only a few business courses at Harvard--he seemed a perfect choice.

Eastern, after all, had been led for 26 years by Eddie Rickenbacker, World War I’s most famous American flying ace. Destiny seemed to demand another hero at the helm, and Frank Borman was in the mold.

He had quarterbacked his high school football team to the Arizona state championship. He had taken flying lessons with money earned from his paper route. He had gone to West Point and was graduated eighth in a class of 670. He had married Susan Bugbee, his high school sweetheart.

By the late 1950s, he had transferred to the Air Force and become a test pilot.

Later, in the then-infant space program, he was an expert in fluid mechanics and thermodynamics. He flew in Gemini 7 and circled the moon in Apollo 8, reading the Bible to “all of you on the good Earth.”

Quick Turnaround

As Eastern’s top man, he turned things around immediately. He pruned from a top-heavy management. He reshuffled routes. He persuaded union workers to accept a wage freeze.

Most of all, he won respect.

“The colonel,” as many employees affectionately called him, seemed an uncommon man cut from common cloth. He did not want a fancy suite of offices. He wore suits off the rack. He drove to work in a rebuilt Chevy, then climbed nine flights of stairs for the exercise.

When he needed a flight, he disdained the corporate jet. He made his own reservations on Eastern and refused preferential treatment. Once, he chewed out an Orlando, Fla., boarding agent who left a paying customer at the gate in order to find Borman a seat.

Most employees felt they knew the boss well. They saw him on television, promising that Eastern’s workers were earning their wings every day. They saw him at curb side, where he’d surprise them by showing up to handle bags.

But, inevitably, Borman’s popularity was tied to the airline’s profit picture. When airline deregulation left major carriers struggling with new rules, Eastern’s picture grew dim and never quite brightened.

In difficult times, Borman pleaded with his workers for concessions. If, for a while, the boss had seemed to be everybody’s buddy, eventually he became a pal with a hand in their pocket.

“For 10 years, we’ve made concessions so he could turn the airline around, and all he’s done is drive the company further and further into debt,” Dan Nutter, an Eastern mechanic, said Monday.

What started as a wage freeze eventually became a variable earnings program where employees, in effect, loaned a share of their gross pay to the airline. The loans were repaid only when Eastern turned a profit.

This was followed by a convertible debenture program, then a stock program. Each time, the employees bet some of their wages on the future profitability of the airline. In 10 years, the various employee give-backs have cost workers more than $200 million, some union officials estimate.

Crisis Every Few Years

At the same time, they cost the astronaut in a business suit the respect of his workers.

Every few years, the airline seemed in crisis. Borman warned of bankruptcy; he pleaded for more concessions.

In late 1983, in what Borman promised were final concessions necessary for corporate survival, employees took pay cuts of 18% to 22% in return for common stock and representation on the company’s board of directors.

Early Monday, a weary Borman admitted that there were no more ways to go, no more peas to pick from under the shell. The airline would be sold.

The purgatory of financial woes now enters a new phase.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.