This Left-Hander Takes the Right Approach to Life

- Share via

ANN ARBOR, Mich. — The left-hander, Jim Abbott--draft choice of the Toronto Blue Jays, freshman pitcher for the University of Michigan--came strolling into a room on the Michigan campus, said hello cheerfully and shook hands with his left hand.

He has no right hand.

In an hour he had to go to baseball practice. Michigan was working out indoors, rehearsing for a road trip to the South. Coach Bud Middaugh wanted to see what the 18-year-old with the unorthodox delivery could do.

Abbott had been king of the hill at his high school in Flint. As a senior he threw four no-hitters, including a perfect game. He also batted .433, with six home runs. But now he was in faster company. “The level of competition is so much higher here. It’s like the majors, compared to high school,” Abbott said.

Two weeks later, the Michigan team flew to Florida for its season opener. The opponent was Villanova. The starting pitcher was the left-hander.

Disability does not, in every case, result in inability. Nothing was going to keep Jim Abbott from playing baseball, and there is nothing he cannot do. Well, almost nothing. “I still can’t do my left cuff link,” he said, fiddling with the shirt button as he spoke.

From birth, Abbott has had nothing but a stub for a right hand, with a very slight protrusion of two fingers. At age 4, he wore a prosthetic hand with a hook. He detested it. It felt unnatural. Strangers gawked at it. So, a year later, his parents let him discard it.

When he was old enough for Little League, he wanted to play. Mike Abbott, an executive with Anheuser-Busch, and Kathy Abbott, a lawyer, did not discourage him. “That was the great part about it. Not only my mom and dad but my teammates, teachers, classmates, friends, coaches, everybody, you know . . . almost to the point of just ignoring it. I never heard anything about it. If anything at all came along that I couldn’t handle, all anybody ever wanted to do was help.

“I think if somebody would have been negative, just said one time, ‘Give it up, Jim, there’s no way you can do it,’ I wouldn’t be here right now.

“I guess that’s the story behind the story,” he said.

There was precedent for his playing ball. Monty Stratton once pitched for the White Sox after losing a leg in a hunting accident, and eventually was portrayed by James Stewart in a film. There was a St. Louis player, Pete Gray, who made it to the majors with one arm, and is the subject of an ABC-TV film called “A Winner Never Quits,” starring Keith Carradine, that will be aired Apr. 14.

Batters tried to bunt on Stratton. They have tried to do the same against Abbott, who understands. “If they think they can bunt on me, let them bunt on me. After I throw enough of them out, they usually figure out that they’d better try something else.”

One high school team had eight batters bunt against him in succession. The pitcher threw out the last seven.

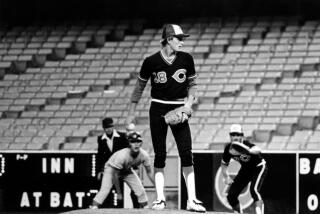

As he prepares to pitch, Abbott rests the back of his right-hander’s glove against his chest. He cradles the glove with his right arm. In one stunningly smooth motion, he extracts the ball with his left hand, slides the glove to the tip of his right stub, inserts the stub into the pocket and throws the ball. Instantly he slips his left hand into the glove.

“I have a little trouble with hard-hit smashes back up the middle, but I’m working on it,” he said.

As a kid, Abbott spent hours throwing a rubber ball against a brick wall and catching it. Transferring the glove from hand to hand became second nature. Scouts who see him do it now--like Don Wilke of Toronto, who convinced the club to select Abbott last June in the final round--scarcely can tell from a distance that the pitcher is doing anything unusual.

“The Blue Jays say they didn’t take me because I was special. They took me because they think I can pitch in the majors,” Abbott said. “I think I can, too. It won’t be easy, but it’s possible. I’m not handicapped. I’m just a pitcher, same as anybody else. Better than some, not as good as others.”

Better than a lot. During his senior year of high school, the 6-3, 200-pounder averaged two strikeouts an inning, was 10-3 with an earned-run average of 0.76, gave up 16 hits in 73 innings and hurled a perfect game in which only two balls were hit in fair territory.

“I’ve grown up daydreaming about pitching in the majors, just like any kid might. I can imagine myself in a starting rotation with Orel Hershiser and Fernando Valenzuela. You know, ‘Now starting for the Los Angeles Dodgers, Jim Abbott.’ But if it never happens, it’ll be because I’m not good enough, not because I’ve got this hand.

“I’ve been introduced to adults and kids with certain handicaps who say they’ve been inspired by what I’ve done. That makes me feel good, but I’m not trying to prove anything to anybody. Except maybe: ‘Don’t let anything stop you from trying.’ ”

In Michigan’s season opener, Abbott had control trouble, and came out in the second inning. A few days later, the same thing happened. “He’s been wild. There’s so much attention on him every time he pitches, it’ll take him a little time to settle down,” Middaugh, the Michigan coach, said Saturday from Florida.

Last Friday night, in Orlando, Abbott was used in relief. North Carolina had runners on first and third with two out. Abbott went 1 and 2 on the batter.

Suddenly, as the catcher returned the ball to the mound, the runner on third broke for home.

“Jim threw him out by a mile,” Middaugh said.

Michigan rallied and took the game. Jim Abbott got the win.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.