Half the Way Home <i> by Adam Hochschild (Viking: $15.95; 198 pp.) </i>

- Share via

At Harold Hochschild’s deathbed, his son puts his ear to the old man’s chest and thinks he perceives a sign of life. “But the nurse tells me that the heartbeat I hear is my own.”

It is a tender ending to a tough book. “Half the Way Home” is the record of Adam Hochschild’s gnawing and all-but-wordless struggle for identity against his father, one of the world’s richest metals tycoons.

The warmth of the last pages is touching after the long chill that precedes them. Yet even the final phrase has a hint of winter. The author aims to confront a painful relationship with dispassion; telling the truth first, and only then making way for whatever reverence may survive.

The reverence that survives is dosed with considerable petulance. Adam intends an act of liberation, but it comes to seem an act of appropriation.

Harold Hochschild’s hand lay on him, solicitous but heavy. Now, the son lays his hand with equivalent weight upon the father. “The heartbeat I hear is my own” sounds a note of possession. “At last,” the reader almost hears.

As head of American Metals Climax, founded by his own father, Harold Hochschild ran a worldwide metals empire with major holdings in South Africa and Canada. He was a hard worker with a certain humane distaste for his own work. He was an early opponent of the Vietnam War and an advocate of relations with Communist China.

At Eagle’s Nest, his baronial lake-side retreat in the Adirondacks, he would assemble house parties that included such figures as George Kennan and the late Adlai Stevenson for horseback riding, water skiing, and serious talk about the state of the world.

He was the epitome of the cultivated businessman who can see beyond his own interests; as a result of cultivating these interests, he was also extremely rich. Adam grew up hearing people tell him that his father was wonderful.

The phrase cut, he makes clear. For him, Harold Hochschild was Father; a stiff, inhibited man of unbending authority; a man alternately aloof and attentive. To Adam, the attentiveness was more fearful than the aloofness. He dreaded the attempted intimacy. When Harold took him out for father-son occasions--in a chauffeured limousine--he would become ill. The father ordered thick steaks, drastically underdone. Adam, skinny and pale, ate and threw up.

“Half the Way Home” alternately knits and picks apart the costly fabric of the Hochschilds’ existence. There were the Adirondack summers with horses and boats and lots of servants. There was travel on ocean liners and stays at grand hotels.

Wherever they arrived, the author recalls, there was somebody to meet them, smiling and able to snip the local red tape. Later, he writes, it seemed strange to him to arrive somewhere and find nobody smiling and snipping.

There was the family’s elaborate establishment at Princeton. Adam was chauffeured to school every day, to his embarrassment. His parents worried that he wasn’t making friends, so they arranged for the local Cub Scouts to be headquartered at the house. The den mother was not Adam’s mother, however, but his governess.

It was a gilded childhood but not, the author remembers, a golden one. Everything, in his recollection, was infected by Father. The recollection is unsparing.

Part of the strain, no doubt, came from the fact that Adam’s parents were middle age when they met, and that Harold was 50 when Adam was born. Almost immediately thereafter, Harold went off to World War II as an intelligence officer. The boy’s first memory of Father is of a middle-age interloper coming between him and his loving and attentive mother.

From then on, Father’s shadow falls over the most innocent pleasures. Even his mother, beloved childhood companion, came to seem an agent of the shadow. He tells of his love for her; he also, somewhat repulsively, quotes a friend who says that she served “to soften me up for father.” He writes of her death as a flurry of arrangements.

Once he grew up, after Harvard and a visit to South Africa--where he observed the social ruins atop the family mines--Adam moved as far from his father’s world as his imagination would permit.

He marched in the Civil Rights Movement of the ‘60s, went to work on Ramparts, and co-founded Mother Jones. The older Hochschild disapproved, not so much on ideological grounds as out of concern that Adam was wasting his life.

Disapproval did not lead to rupture, though. Adam recalls disapproval as a permanent condition; the relationship occupied a limbo devoid either of outright repression or outright rebellion. We are not told, for example, whether there was ever a threat to cut his funds.

For that matter, we are not told whether he got any funds. It is an odd omission in a book that attempts so searching a look. It makes one wonder whether the author is holding back; and perhaps not on that count alone. The central problem of “Half the Way Home” is that the figure of the father never emerges clear from the child’s injured recollection.

It is a contemporary belief that you have to free yourself from the dead in order to reverence them. It marks of a number of child-father memoirs: Geoffrey Wolff’s “The Duke of Deception,” Susan Cheever’s “Home Before Dark,” Lance Morrow’s memoir of his own father, and others.

Of course, in many civilizations and during most of our own, it was the other way around. We reverenced the dead in order to free ourselves from them. Monuments, odes and the lot. Asian ancestor worship may seem quaint in this day and age, yet Hochschild’s book, for all the sensitivity and pain with which it is written, makes something of a case for it.

Blood flows from his truth, and we wonder how much truth has been told. Is the purpose of a memoir to re-fight old battles and redistribute the victory; or to transcend them both?

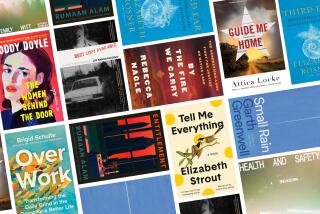

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.