From Rags to Pizzas and Tigers

- Share via

Horatio Alger would have loved Tom Monaghan. So would Charles Dickens. He’s every Tiny Tim or Raggedy Dick, Luck and Pluck, Ned the Newsboy or Bert the Bootblack dime novel ever penned.

He’s the American Dream, God and country, Stars and Stripes Forever all wrapped in one. Color him red, white and blue. Sculpt him on Mount Rushmore, too.

What do you want, the Marine Hymn? Tom Monaghan was there too.

You didn’t believe this kind of story was possible in late 20th Century America?

All right, try this on your imagination: There’s this little boy who grows up in Ann Arbor, Mich., to a poor but honest family. The father dies on, of all days, Christmas Eve when our hero is only 4 years old.

He grows up in orphanages. His mother doesn’t want him and can’t cope. It is the cruelest kind of rejection. Life is a rudderless drift from orphanage to foster home to detention center. He dreams of a farmhouse with white fences and he is given a hall with bars on the window. He has never done anything wrong, but his childhood is a prison.

On the infrequent occasions he is home, his mother throws things at him. She, poor creature, is caught in the same coils of social defeat and despair, and retreats into a mental breakdown and demons of her own.

He makes Oliver Twist look like Little Lord Fauntleroy. He wasn’t a child, he was an inmate. The nuns didn’t mean to be cruel, just strict. To a 7-year-old boy it came out to the same thing. Waxing floors with bread wrappers was not the standard Saturday Evening Post cover kind of upbringing.

The stigma wasn’t the boy’s, but it clung to him all the same, just as tenaciously. But far from being turned to a life of crime by all this injustice, young Tom turned to religion. He wanted, of all things, to be a priest. The seminary was skeptical. A young man who couldn’t get along with his mother was hardly your basic St. Francis or Father O’Malley material, now, was he? What kind of part was that for Bing Crosby? They expelled him for the terrible crimes of pillow-fighting and whispering in church.

Tom Monaghan did what you might expect. He got a gun. But not for what you might think. He didn’t stick up banks, or join gangs. He joined the Marines.

Boot camp made the orphanage seem a day in an ice cream factory. When his mother wrote the base commandant, complaining that her son never wrote--given their relationship, this was laughable--the Corps did its best to straighten him out. This included dragging him out of the shower naked to give him a beating in front of the barracks.

Tommy began to make Little Orphan Annie look pampered. One would guess from that bleak beginning that young Tom Monaghan was probably one of those guys who would be institutionalized for life, that he would no longer be a name, just a number.

Tom Monaghan just took it as evidence that God loved him.

He got ahead the way every Horatio Alger hero did--hard work. He kept the commandments. He kept the sacraments. He kept the faith.

He didn’t save the boss’ daughter from a team of runaway horses or get her out of a burning building. He didn’t happen to blacken the boots of the president of U.S. Steel. He made it the hard way.

He wanted to be an architect. Frank Lloyd Wright was his idol. But he found his destiny in a much less lordly work of art--the all-purpose pizza pie.

His brother came to him with a proposition that they take over a pizza parlor in Ypsilanti. It wasn’t much, just a storefront on a back street. But for Tom Monaghan, it was Camelot. Edison coming upon the electric light.

Tom Monaghan didn’t sell pizzas, he lived them. He cooked them in his store window. He delivered them, experimented with them. He tried new methods to mass produce them and still keep quality.

“A pizza is part artistry and part chemistry,” he said.

He slept in his car and kept his books in his pocket. You could compute the day’s business by the stains on his clothes. He loved it.

He made and marketed his pizzas under the trade name Domino’s and later fought a long and costly fight with the sugar company to keep the title.

He expanded fast. So fast, it cost him control of the company for a time in the early 1970s. “I was a reverse millionaire,” he admits. “I owed a million dollars.”

He disdained the advice to go into bankruptcy, reclaimed his company and paid off creditors 100 cents on the dollar. Domino’s today is a 3,600-store operation that does $2-billion worth of business every year.

But back in the days when Tom Monaghan was a kid in the orphanage, he never got the things other kids got. He never got a new bike or a set of trains or a football for Christmas. The first car he ever owned was used to deliver pizza.

So one Christmas, he saved up and bought himself a new $25 baseball mitt. It was the prized possession of his youth. He slept on it, he never let it out of his sight. He kept it till it was worn and tattered.

He was a card-carrying, deep-dyed baseball fan of the first magnitude, and the Detroit Tigers were his team. He thought Al Kaline walked to work every day on the Detroit River. He knew every player and what that player hit on the 1968 world championship team.

“The highlight of our year in the orphanage was when they took us to Tiger Stadium,” he said. “I never wanted the game to end. I never wanted to go home.”

In 1983, Tom Monaghan’s rags-to-riches saga took a turn not even Alger would have thought of. For $53 million, he bought the Detroit Tigers.

Now, historically, baseball teams have been thought of as play toys for the big rich. Instead of a yacht or a string of polo ponies, they bought the Cubs or the Yankees. It wasn’t an investment, it was a hobby.

But, as Jacob Ruppert proved in New York and Gussie Busch in St. Louis, the ownership of a fine baseball team can be a shrewd investment and as sure a way to modern immortality as the ownership of a fine library.

And the boy from the orphan asylum finally got a break. The Tigers won the pennant and World Series his first year, a public relations stroke of the first order. It gave him the instant cachet and identification other avenues might take years to effect.

“Owning the club established my status in the business community and opened a lot of doors for me socially,” Monaghan admits.

Tom Monaghan tells his remarkable story in a new book called “Pizza Tiger,” published by Random House and in the bookstalls for the Christmas book trade. Its sub-title should be “Don’t get mad, get the Detroit Tigers.”

It could have one of those derring-do titles Alger used to put on his books because it illustrates the moral the good Horatio preached in more than 100 volumes--that a deprived childhood does not necessarily lead to a depraved manhood, indeed that it might be an asset. This book, like the man, is as direct and no nonsense as a Marine landing, and it’s as All-American fare as a pizza with everything and a diet Coke.

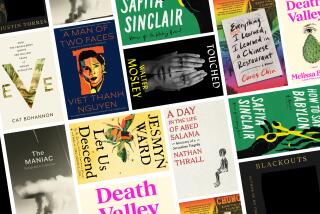

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.