The Great Journey: THE PEOPLING OF ANCIENT AMERICA by Brian M. Fagan (Thames & Hudson: $19.95; 288 pp., illustrated).

- Share via

How and when did humans “journey from Asia into a vast, seemingly unpopulated landmass” that has come to be known as “the Americas”?

This is how Brian M. Fagan phrases the question that, in one form or another, has puzzled Western civilization as far back as the earliest arrivals by European explorers on this side of the Atlantic. To answer the question, Fagan concentrates upon significant archeological studies representing more than four centuries of research.

The range of his concise book is impressive. In the first two chapters alone, Fagan interprets with reasoned hindsight the findings of more than 50 historical and scientific sources.

“The Great Journey” was written not for scientists, however, but for general readers. It will appeal to persons who may not know the difference between “acid rain” and “amino-acid racemization” but who are fascinated to learn how the latter process, developed in 1975, has enabled scientists to date (as far back as 100,000 years ago) human bones that archeologists have unearthed. Such modern techniques make it possible to deduce more precisely when early Homo sapiens may have first settled in North and South America.

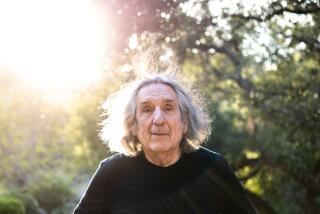

For armchair archeologists, then, Fagan, a British-born anthropology professor at UC Santa Barbara, tells the larger story. Through a systematic narrative, he examines the logical development of scientific evidence and well-supported theories, primarily since the 1850s, about “the peopling of ancient America.”

In analytical style and illustrated format, “The Great Journey” is similar to “In Search of the Trojan War” (Facts On File, 1985). In that book, British author Michael Wood examined the equally controversial quest, spanning more than 2,000 years, to authenticate Homer’s legendary city of Troy. This popular approach has been one of Fagan’s trademarks as a writer, beginning with his successful book, “The Rape of the Nile” (Scribner’s, 1975).

In this latest work, the 51-year-old professor remains careful not to embrace any particular view, though he seems most comfortable with the well-established theory that Asians, generation by generation, pursued mammoth and bison across Siberia and across what was then a land bridge to Alaska.

These “first Americans” may have journeyed along a glacier-lined corridor and settled--by conservative estimates, at least 10,500 years before Columbus--in what Fagan describes as “a world to itself, a magnificent diversity of environments.”

If this theory is accurate in its timetable, then the prehistoric odyssey of people (whose descendants Columbus wrongly assumed to be “Indians”) was an epic land journey even more intriguing than Marco Polo’s to China. These ancestors of what evolved into nearly 2,000 American Indian tribes ventured into the unknown under far more dangerous conditions than those that faced the Ventian merchants who crossed China’s Great Wall 9,700 years later.

One of Fagan’s most evocative observations is that, before the 1580s, a Jesuit missionary in Mexico and Peru, Jose de Acosta, proposed this same theory about what scientists now call the “Beringian land bridge.” Acosta’s speculation is more impressive, Fagan explains, because it was written nearly 150 years before Vitus Bering sailed through the Bering Strait in 1728 and more than 300 years before geologists in 1970 confirmed that the strait may have been a land bridge only twice in the last 125,000 years.

The major absence in “The Great Journey” is, in fact, what is missing in contemporary knowledge about native American cultures. For the Trojan War, the Greeks had Homer, but there appears to have been no Homer to compile and record an American epic, preserving the oral traditions that such a journey must have inspired.

Consequently, Fagan and other scientists are left holding animal bones, stone tools, chipped projectile points and the results of dental and blood-serum comparisons--crucial, but slender elements from which to reconstruct one of the world’s grandest stories. Without such a mythic basis, to which Fagan could compare scientific findings, “The Great Journey” is less compelling reading than some of his earlier books.

However, for fans of Jean M. Auel’s three best-selling novels, Fagan’s book provides a much-needed and up-to-date summary of the facts on which her book about Ice Age humans, “The Mammoth Hunters” (Crown, 1985), was loosely based.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.