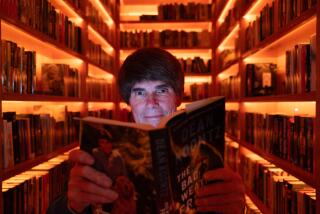

Morality Play in a Halloween Costume : TWILIGHT EYES <i> by Dean R. Koontz; (Berkley: $4.95; 464 pp.)</i>

- Share via

I made the mistake of opening “Twilight Eyes” late at night, when everyone else in the house was asleep, and I quickly succumbed to the sheer hypnotic allure of Dean R. Koontz’s chilling tale of a race of murderous mutant-changelings and the brave but benighted souls who are driven by their own nightmares to do battle with these “goblins.” By the time I put the book down, all kinds of things were going bump in the night--and not just in the pages of the book.

Koontz is one author of best-selling thrillers who approaches his genre with deep respect, worthy ambition and the utmost seriousness of purpose--he sets out to scare the wits out of us, and he succeeds in doing so without resort to either one-dimensional screenplay prose and plotting or sex and violence of pornographic intensity. Rather, he aspires to take us, as his narrator puts it, “not merely . . . on a Hansel-and-Gretel journey into the spooky witch-woods but into a far more frightening place, into a monstrous memory of a childhood under siege.” And the best moments of “Twilight Eyes”--where Koontz evokes the gritty details of carnival life and imbues the scene with an almost palpable atmosphere of moral peril--remind me of Ray Bradbury.

The tale begins in the year of President Kennedy’s assassination, 1963, which is gloomy and portentous enough even without the further revelation that our world is stalked by a race of “goblins,” who live among us in human form while indulging their indecent passion for human suffering by contriving to cause everything from farm accidents to classroom fires to nuclear holocaust. Koontz encourages us to regard these creatures as a metaphorical expression of evil at large in the world, ranging from the microcosmic evil of the sexual psychopath to the macrocosmic evil of nuclear holocaust, but the goblins and the ill they do are rendered quite literally in “Twilight Eyes”--”For me,” declares Slim MacKenzie, the 17-year-old roustabout who turns out to be an all-purpose avenging angel, “it was Grand Guignol time again.”

The goblins, we learn, can be perceived in their true form only by a handful of men and women who are gifted with certain forms of extrasensory perception--Slim MacKenzie can see through their human trappings; Horton Bluett, an aging coal miner who stumbles across their preparations for Armageddon, can smell them. Koontz has created a vast construct of the imagination to explain these creatures and their bloodthirstiness. One of the many, many twists of fate in “Twilight Eyes” is the revelation of how the powers of the goblins and their righteous pursuers are the result of the same catastrophe of ancient human history.

Slim and his lady love, Rya Raines, have each struggled against the goblins since childhood, but the battle is fully joined when he signs on with a seedy but oh-so-atmospheric itinerant carnival that stops in the little Pennsylvania mining town where the goblins are preparing their final assault against humankind. The rendering of the carnival--especially its odd but engaging denizens--is superb, and superbly scary; Koontz has captured the unvarnished appeal of the old-fashioned carnival to our taste for thrills and titillation, and he spares no adjective or adverb in service of his set piece.

Koontz styles himself as a kind of Hieronymus Bosch of the thriller; he loves to seize upon a scene and embellish it in meticulous detail, allowing us to see the face of every creature and torment of hell. But in his cosmology, the carnival is not a repository of evil; rather, it’s a sanctuary from evil, a place where the coarseness and freakishness of the carnies conceals a sturdy moral resolve that is the ultimate weapon against the goblins.

Indeed, Koontz brings an unmistakable (and, I believe, laudable) sense of morality to his tale of terror. “Our greatest treasure, hope, remains,” his hero observes in passing. “It is both the most pathetic and noblest thing about us, the most absurd and admirable quality we possess, for as long as we have hope, we also have the capacity for love, for caring, for decency.”

In his moments of struggle and pain, Slim engages in an existential debate with the Almighty: “I alternately raged at God and blessed him, bitterly accused him of cosmic sadism one moment, and, seconds later, weepingly reminded him of his reputation for mercy.”

Maybe it’s because I finished the book in broad daylight, comfortably surrounded by dogs and children, but the efficient cataclysm at the end of “Twilight Eyes” seemed a lot less frightening than the slow, measured, almost solemn opening passages. But no matter--once you have glimpsed the nasty demons of Koontz’s creation, you will want to watch as Slim MacKenzie and the woman he loves descend into hell on Earth and strike a blow against purest evil.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.