The Lawyer of Choice: Court May Decide if It’s a Right

- Share via

SAN DIEGO — With his trial less than a week away, Mark Erick Wheat was on the verge of panic in the late summer of 1985.

It was a feeling that had been growing since the previous December, when he was indicted in a case in which more than a dozen people eventually were charged with conspiracy to distribute large amounts of marijuana.

Wheat, also known as Mark Chum, had stored at least 12 tons of marijuana in the garage of his Escondido home for nearly three years beginning in 1981, federal prosecutors alleged.

Wheat, then 32, faced the imminent possibility of a long prison term and a substantial fine as he sat in the office of his lawyer, David Semco, shortly before trial. But a new strategy, they later explained in court, gave them a glimmer of hope.

Successful Lawyer

There was another lawyer in town, Eugene Iredale, who had recently beaten the same federal prosecutors at a jury trial in a related case. The government’s key witness in that case was scheduled to be the key witness against Wheat. Iredale also had arranged a favorable plea bargain for a second defendant charged in the scheme.

They decided to try to hire Iredale and put to use his knowledge of the case and the key witness.

And they seemed to be in luck. Iredale, they learned, was free for the next two weeks and, after a daylong session in his office, agreed to take the case.

But it was not that simple.

When prosecutors learned that Iredale was planning to represent Wheat, they filed a strong objection with U.S. District Judge Lawrence J. Irving, arguing that Iredale would have a conflict of interest if he were allowed to represent yet another defendant in the alleged conspiracy. The problem, they said, was that one of Iredale’s earlier clients might be called as a witness against Wheat--putting the lawyer in an untenable situation.

Irving agreed and barred Iredale from the case. Wheat was convicted and sentenced to 10 years in prison.

Court to Hear Case

Now, more than two years later, the U.S. Supreme Court is set to hear oral arguments on whether Wheat had a right to the lawyer of his choice, despite the government’s claim of a conflict. Wheat is free on bond while he awaits the court’s decision.

It has been long settled by the courts that a judge can bar a particular lawyer from a case if it is clear there is a conflict of interest. But federal courts around the country have issued conflicting opinions on whether a defendant, made aware of a potential conflict, should be allowed to use such a lawyer anyway.

In the complex Wheat case, defense lawyers allege that prosecutors raised the objection of a conflict of interest to mask their true desire--to avoid facing a top defense attorney who had already beaten them once.

“It’s the ‘Too Good Lawyer’ objection,” said John Cleary, a San Diego attorney who will argue the case before the Supreme Court in early March. “The prosecutors knew they were outclassed and outgunned.”

In his brief to the Supreme Court, Cleary contended that any potential conflict of interest was speculative at best and that prosecutors “should not be given near plenary control over who is to be his opposing advocate.”

“In the absence of a clearly proven actual conflict, a criminal defendant is entitled to select counsel of his choice,” Cleary said.

Prosecutors, however, said the possibility of conflicting interest was quite real and that Iredale’s continued involvement tainted the case.

Constitutional Guarantee

In its brief filed with the Supreme Court, the Justice Department argued that the Sixth Amendment, while guaranteeing defendants the right to counsel, does not guarantee a defendant “the right to the services of a particular lawyer.”

Even though Wheat may have been willing to waive his right to a conflict-free lawyer, “he cannot waive the independent public interest in the fairness of criminal trials and the integrity of the legal profession,” the Justice Department said.

The alleged conflict involved two defendants. One was Juvenal Gomez-Barajas, who prosecutors contended was Wheat’s superior in the marijuana conspiracy but who was acquitted of drug conspiracy charges at a jury trial during which he was represented by Iredale. Gomez-Barajas later pleaded guilty, however, to an income tax charge.

The other was Javier Bravo. The week before Wheat’s trial was scheduled to begin, Iredale appeared before Judge Irving with Bravo, who pleaded guilty to a conspiracy charge. In exchange for the plea, prosecutors offered to recommend probation and no more than 30 days in jail.

At the end of that proceeding, which occurred on a Thursday afternoon, Iredale notified Irving that he intended to represent Wheat at his trial set to begin the following Tuesday.

But Michael Lasater, the assistant U.S. attorney handling all three cases, objected. Lasater conceded that the government had no plans to call Bravo as a witness at Wheat’s trial, but said that it was “always a potential.”

As for Gomez-Barajas, he had not yet been sentenced on the income tax conviction, Lasater said, and could still withdraw his plea and request a trial. If so, it was possible that prosecutors would call Wheat to testify about Gomez-Barajas’ alleged marijuana dealings on the question of Gomez-Barajas’ net worth.

Lawyer’s Rejoinder

Iredale responded that such a change of heart by Gomez-Barajas was highly unlikely and that none of the three defendants had any objection to his involvement in all three cases.

“Frankly, I see no conflict,” Iredale said. “Mr. Wheat wants me to represent him. Mr. Gomez has no objection. His case is resolved and I don’t even think Mr. Lasater’s hope of resurrecting it constitutes any possibility.

“And Mr. Bravo has indicated to me that he has never met Mr. Wheat, doesn’t know Mr. Wheat from Adam, and even if the government wanted to call him he could not implicate Mr. Wheat in any way,” Iredale said.

“I would hope the government would not be engineering conflicts to try to get their selection of counsel for the case,” he told the judge. He suggested that Lasater was trying to “shop” for the defense attorney of his choice.

The next Monday, the lawyers appeared before Irving again to try to settle the matter. That, according to Iredale, is when Lasater approached him with a new offer for Bravo: If he would testify against Wheat, the government would drop its request that he spend 30 days in jail and would recommend straight probation.

“If you’re playing chess and you’re the government, this is a beautiful move,” Iredale said in an interview, noting that this development seemed to put his clients directly at odds.

Bravo accepted the government’s offer, but even so, there was no conflict, Iredale said, because Bravo knew nothing that could damage Wheat. Bravo ultimately testified about a marijuana delivery involving other defendants.

In the end, Iredale said, the case against Wheat was based largely on the testimony of Victor Vidal, a middleman in the marijuana conspiracy who agreed to cooperate with the government.

Government’s Position

Lasater said he could not comment on the case outside of court. But during court proceedings he denied that he was trying to choose counsel for the defendant. The government, he said, believed Iredale had a very heavy conflict in the case and should not be permitted to represent Wheat.

Irving conceded that the dilemma presented him with a “very tough decision.”

“Were I in (Wheat’s) position, I’m sure I would want Mr. Iredale representing me, too,” Irving said. “He did a fantastic job in that (Gomez-Barajas’) trial and I’m sure Mr. Wheat would like to have him representing him.”

However, Irving said, based on the representations of the prosecutors, “The court really has no choice at this point other than to find that an irreconcilable conflict of interest exists.”

In a decision handed down last April, the Circuit Court of Appeals agreed with Irving and the Justice Department, saying that Iredale’s defense of Wheat would “very likely” have created a conflict of interest.

“What really is the tragedy in this case is that the government was able to manipulate a situation to get rid of a lawyer to whom no one objected except the government,” Iredale said last week.

Although he is not an attorney of record in the case, Iredale has been consulting on the Supreme Court appeal with Cleary. The two men know each other well: As head of the Federal Defenders Office in San Diego at the time, Cleary hired Iredale when he graduated from Harvard Law School in 1976. Both are now in private practice.

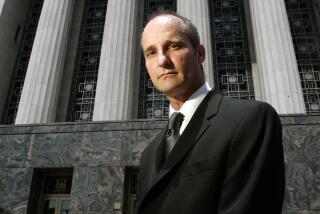

Iredale, 36, is known as one of the more aggressive lawyers practicing in the San Diego federal court, where he has opposed Lasater numerous times.

“As a human being, you could not hope to meet a nicer, more decent person,” Iredale said. “But what he did in this matter as a tactician was very tricky, was very cute. It deprived a defendant of his constitutional rights.”

A decision in the case is expected late this year.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.