Our New Cultural Imperative : The Study of Western Civilization Is Insufficient

- Share via

During the recent visit of Mikhail S. Gorbachev, the most sophisticated efforts were made to decipher every nuance of his words and actions. It would have been more rewarding if Americans had decided to pay attention to learning the language and studying the culture of Gorbachev’s people. That would require an act of glasnost of our own to remove our national blinders on the study of foreign languages and non-Western cultures.

As a college president, I have often told students that a liberal education is “the surest instrument that Western civilization has yet devised for preparing men and women to lead productive and satisfying lives.” I now wonder whether that declaration was not too narrowly framed.

An unqualified emphasis on “Western civilization” blocks access to non-Western cultures and legitimates an assumption of European and American cultural superiority. That assumption stands in the path of a better understanding of the Soviet Union. It is as damaging to our nation as it is menacing to the world that our students will be compelled to understand and to shape.

This is precisely the time, when a number of voices in American life are suggesting that college courses be devoted almost exclusively to Western literature, that we should be looking far beyond our own culture. We need to worry, as Prof. Allan Bloom has reminded us, about “the closing of the American mind,” but we should worry as well about the opening of the American mind.

As a corrective to our traditional emphasis on Western civilization, we need only recall the 12th-Century European discovery of scientific and mathematical works written in Arabic. It was not political or geographical barriers that had kept Western scholars from this body of knowledge until the time of the Crusades. It was a psychological and cultural indifference to non-Western achievements. But without the development of algebra, to say nothing of the concept of the zero and the Arabic numerals themselves, modern Western advances in mathematics and sciences would be literally unthinkable. Within 100 years after translation of Arabic texts began, scholars throughout Europe were making use of the fruit of Middle Eastern study in medicine, biology, mathematics, physics and astronomy.

Newton was right in saying, “If I have seen farther, it is by standing on the shoulders of giants”; we must remind ourselves and our students, as we seek to organize knowledge, that the sturdy feet of some of those giants were planted firmly in the East.

Of course it is important for successive generations of students to appreciate and possess the Western tradition. But it is essential, too, for them to recognize that the Western tradition is only one of the world’s great cultural traditions. In Asia, in Africa, in the Islamic world, in Latin America, in Russia, there are ancient traditions that must command our attention, traditions that have shaped the world our young people will inherit.

*

The understanding of other cultural traditions begins with language. The study of a nation’s language often reveals the values of a foreign culture more tellingly than a dozen weighty treatises. It illustrates the intimate bonding that exists between style and content, between cadence and substance, between idiom and national character. It makes clear that human beings are as much the creatures of their language as they are its makers.

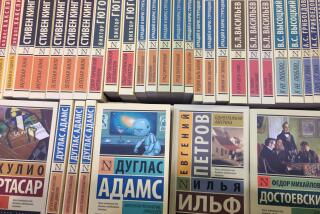

One of the United States’ most distressing deficiencies is our growing inability to communicate with other nations because we lack proficiency in their languages. Less than 5% of our high school graduates attain meaningful foreign-language competence. In 1979 it was determined that about 10 million students in the Soviet Union were studying English, while only 28,000 American students were studying Russian. The figures are only slightly better today.

Similarly, educators in the People’s Republic of China proudly tell visitors that 250 million Chinese either speak or are studying English. If that is true, China is on its way, as one wag has said, to becoming the largest English-speaking country in the world. The number of Americans who can speak Chinese remains minuscule.

It is widely accepted that a key factor in the remarkable success of the Japanese in capturing such a large share of our markets has been their determination and skill in mastering English.

The United States has often been compelled to make foreign policy in a cultural vacuum. In the years preceding the war in Vietnam, only a handful of American-born specialists in the State Department or teaching in American universities understood the language or culture of Vietnam, Cambodia or Laos. And in the revolutionary year of 1978, only six of the 60 foreign-service officers assigned to the U. S. Embassy in Tehran were even minimally proficient in Farsi, the language of Iran.

As the locus of world politics and international trade is shifting from countries that speak English, Spanish, German and French to countries that speak Russian, Chinese, Japanese and Arabic, the United States is failing to keep pace in the education of men and women who can read and speak these languages.

It would be easier, of course, to continue insisting that the rest of the world learn English. But such a complacent expectation has already placed Americans at a serious disadvantage in the international marketplace and at an even more serious disadvantage in diplomatic affairs. By expecting others to learn our language while we do not attempt to learn theirs, we are isolating ourselves from a wide range of opportunities--diplomatic, economic and cultural. We are limiting our capacity to trade in ideas no less than in services and products.

Of all the messages we have deciphered from General Secretary Gorbachev’s visit, the most important is one of the least mysterious: the need to educate Americans to speak his country’s language and more fully appreciate its culture.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.