Talk-Show Host Leaves Panic Behind : KVEN Figure Finds a Way to Overcome Agoraphobia

- Share via

Today, he cheerfully banters with perfect strangers over the airwaves, leads a Fourth of July marching band with fans toting transistor radios and, occasionally, slips behind the steering wheel of a stock car.

But this very public man, who says in his disarmingly frank way that the public likes him for his “moderately enormous ego,” used to be excruciatingly self-conscious.

For 10 years, Ventura radio talk-show host Ross Olney was hounded by panic. Back then, even walking to the mailbox in front of his house, standing in line at the supermarket or sitting down to dinner in a restaurant set off waves of nausea, sweating and dizziness.

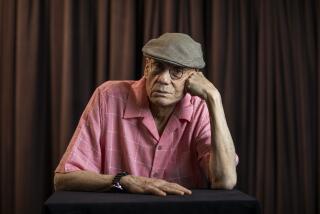

The host of KVEN’s 3-hour morning show, now the very image of a gregarious bon vivant, once suffered from a psychological disorder that caused him to withdraw from people. But Olney, who at 58 resembles a younger version of Peter O’Toole, doesn’t find his past as incongruous as others might. “There are far more agoraphobics than people imagine,” he said.

Indeed, some 13 million Americans suffer from agoraphobia--a disorder that researchers now believe may be genetically passed from parents to their children, according to Dr. Arthur B. Hardy, a psychiatrist in Menlo Park, Calif., who has developed an approach to treating agoraphobics that is used in more than 60 mental health clinics.

In 78% of those cases, a bout begins with a sudden panic attack that Hardy, a past president of the Phobia Society of America, describes as “a feeling of absolute doom.”

“Everything will be going along fine and then, suddenly, they have this horrible sensation and, right away, avoidance sets in. The more things you start avoiding, the worse it is.”

The trap has closed shut on everyone from awkward high school students to successful business people. Even Willard Scott, the bubbly weatherman on NBC’s “Today Show,” is a recovered agoraphobic. Scores of published and broadcast accounts have explored the disorder in the last few years, perhaps making it a bit less frightening for those afflicted with it.

That was not the case, however, when the author and talk-show host first sensed that something was drastically wrong. Olney, who agreed to recount his experiences in the hope of helping others, was 28 years old.

After moving his young family to California in the late 1950s, Olney suddenly and inexplicably became “super-shy.” A former radio operator for the Air Force who was nearly shot down twice during the Korean War, he had abandoned a secure job on an automobile assembly line in his hometown of Lima, Ohio, for the hit-or-miss existence of a free-lance writer.

Started to Avoid Situations

Longer on rejection letters than paychecks, he began to notice that he didn’t want to go anywhere. He started to avoid situations that he couldn’t get out of gracefully. But he was managing, he thought.

In fact, he began to feel more sure of himself when, after 2 years, he wrote off his career as a free-lancer for a more stable job as an editor for the Lynwood-based Skin Diver Magazine. Otherwise, he says now, he would never have agreed to do what turned out to be a fateful lecture on underwater warfare.

An article he had written about underwater propulsion devices had attracted the attention of a Long Beach naval officers’ club, which requested a speaker on the topic.

Originally, Olney was only going to write the lecture, and the magazine’s advertising director was going to deliver it. But when Olney’s colleague discovered a scheduling conflict, the author was tabbed for the task.

Unexpectedly, the former Air Force staff sergeant had to confront the prospect of losing face before the men that he still considered, even after several years of civilian life, as his superiors. Olney, a mere writer, was convinced that he didn’t have anything to tell them that they didn’t already know.

“It terrified me,” Olney recalled.

So did the scene at the club.

“This full admiral sits down on one side, and on the other side is a four-star general,” he said. “Everything was wrong.”

At the microphone, he dropped his notes. His hands began to shake uncontrollably. His face broke out in sweat. He felt nauseated and faint. Unable to utter a word, he excused himself and dashed into the restroom.

“I threw cold water on my face and then just kept going and never looked back,” he said.

To this day, Olney wonders how the officers filled the void left in his wake. But there was no question as to the effect on his life.

“From that point on, it was downhill,” he said.

Shunned Interaction

He withdrew at work, refusing to make any sort of public appearances, ferreting himself away in the back of the office and shunning personal interactions in favor of telephone conversations. But when new owners bought the magazine and told staff members that they would have to demonstrate skin-diving equipment as a part of their jobs, Olney realized he would have to change.

He couldn’t. He briefly took another job, but quickly quit it, too. Finally, he returned to the socially unchallenging life of a free-lance writer. And, this time, Olney hit his stride and began selling what would eventually amount to, according to his count, 162 books. But his success felt empty. Like a physical disability, the affliction had taken over his life.

“It controls you,” he said. “Everything you do, you have to take your agoraphobia into consideration. You have to plan everything and rehearse it and hope that nothing upsets your plans.”

Olney dreaded the short walk to the mailbox, sometimes leaving the task to his wife after she returned from her job in the evening.

At the grocery store, he found himself abandoning shopping carts full of food because standing in line threatened to set off a panic attack.

Predictable Confines

He no longer took his family to conventional restaurants and movie theaters, sticking instead to drive-ins because they enabled him to stay in the predictable confines of his car.

He refused to take his three sons to amusement parks, again morbidly dreading the lines.

All are symptomatic of agoraphobia, Hardy said, although the textbook definition of the word is the fear of open spaces. An agoraphobic’s fears are fueled by deep-seated survival instincts, the psychiatrist says.

“If you got too far away from your cave, you were vulnerable,” Hardy explained. “We don’t have caves anymore. We have condominiums. But the instincts are the same.”

Some agoraphobics become housebound, but Olney never was.

Olney says his fear was less neatly defined. It was the fear of being trapped in an unfamiliar situation and forced to carry out an act, any act--whether that was strolling to the mailbox, standing in line somewhere or even signing a check in front of a clerk.

Unfamiliarity Factor

Anything unfamiliar or the least bit unpredictable, he feared, could set off a panic attack that, in turn, would set him up for the same sort of humiliation he experienced at the officers’ club.

“What if I’m in there,” he remembered thinking in countless situations, “and I start to perspire? It’s going to look stupid if I have to walk out. What will these people think of me?”

The fear kept him hostage to only situations that he could control. As long as he was with his wife, in his car or at home, he was fine. But, even attempting to pay a traffic fine, he would be too terrified to approach a courthouse clerk for instructions.

“I didn’t lock myself in the house,” he said. “I was getting trapped in a place where . . . I’d go to any lengths to avoid a panic attack.”

He once made up an excuse to leave an important meeting with some of the magazine editors who had been publishing his work. He had been afraid that the meeting, held in their offices, would set off a panic attack, and he had postponed it several times for that reason.

Worst Fears Realized

Sure enough, as soon as he arrived, his worst fears were realized. The men closed the doors to the office. Olney was trapped. The situation was in their control.

“Oh, gee, I forgot something,” he recalled lying to them. “I’ll be right back.”

Once outside the office, he made a beeline for his car. He collapsed in yet another panic attack.

Later, returning to the meeting as though nothing had happened, Olney explained to the editors that “they probably had a lot to do,” and because he did, too, he would be leaving. The editors, he recalls noting, appeared to find his actions quirky but not outlandish.

But that was understandable. By this time, Olney had become a master of deception. In fact, even his wife, Patricia, had no clue as to the depth of his problem. She chalked up her husband’s “hermit-like existence” to his chosen craft.

“I knew that he didn’t want to speak in public, but I just attributed that to his being a writer,” she said.

Mysterious Malady

For a little while, Olney even was able to hide the disorder from himself. He originally dismissed his behavior as a lack of self-confidence, even though a new house and the new lease on his writing career belied the explanation. He pored over books on self-esteem, but to no avail.

In fact, nothing made sense until he read a book on agoraphobia.

But the book only put him halfway home. Although Olney realized that he needed professional help, he shied away from it, he now says, because being “trapped” in a closed room with a new person--even a psychotherapist--was precisely the sort of situation that set off alarms.

The cure came in the form of a simple request from his second son, Scott. Then in grade school, the boy came home one day beaming with pride. His teacher wanted Ross Olney, the writer, to speak to the class.

At first, Olney, who was 41 at the time, told the boy that he couldn’t do it, that he was busy--even though no date had been mentioned. Then the teacher called to badger him, and there was another round of pleading from his son. In the end, Olney relented.

“You don’t want to disappoint your kids,” he said.

Studied Layout

Over the next two weeks, Olney prepared for his brief appearance. First at night, then later in daylight, he walked over to the school, stood outside his son’s classroom and cautiously laid his hand on the doorknob.

Peering through a window, he studied the layout of the classroom, mapping where he would stand and rehearsing his presentation. Having observed two desks for adults in the room, he telephoned the teacher to learn which he would use as a podium. No detail could be left to chance.

Nevertheless, the event proved “extremely uncomfortable.” Despite a batch of books and other visual aids designed to draw attention away from himself, Olney felt perspiration drench his face and sting his eyes. Still, he stumbled through.

“I was scared of the teacher,” he recalled. “I was scared of the kids. It was a tiny, tiny step, but I needed it.”

But as painful as the experience had been, Olney remembers feeling exhilarated immediately afterward.

“I was buoyed by it,” he said. Still, he is quick to point out: “I didn’t think, ‘Hey, wow. Now I can go talk before the Democratic convention.’ ”

Stumbled Onto Treatment

Without knowing it, Olney apparently stumbled onto precisely the sort of approach Hardy recommends for treating the disorder. (“I don’t like to call it a disease because that sounds like something you can take a pill for and get well,” he said.) The cure, says the psychiatrist, lies in risking “enough anxiety to get over it, but not to further traumatize yourself.”

Some agoraphobics seem intuitively to understand this and, as with Olney, are able to treat themselves, Hardy said.

Others, however, require professional counseling, sometimes with the additional assistance of tranquilizing drugs. For them, Hardy organizes repeat visits to such dreaded spots as a grocery store. With each visit, the agoraphobic is coached to get closer to the store until he is able to stand in line and make a purchase. Finally, he braves the visit without Hardy.

“We take them by the hand and let them face things,” Hardy said.

Although he never treated Olney, the psychiatrist says Olney’s symptoms were consistent with a moderate case of agoraphobia.

‘He Was Handicapped’

“But even that is enough to materially change his life,” Hardy said. “He was handicapped; he couldn’t do things that other people do.”

Hardy has treated agoraphobics so severely affected that they are bed-bound and “can’t get up but to go to the bathroom.” On the other extreme, he points out, is a woman who called him seeking treatment because “she could only get as far as Spain and she wanted to go to Italy.”

Olney began his bouts at around the age when people are most susceptible to agoraphobia, Hardy says.

Between the ages of 17 and 27, the risk of a panic attack that precipitates agoraphobia is highest, Hardy said. That is when people are faced with life’s greatest challenges and are the least equipped to deal with them, he explained.

“It will take 10 or 15 years of the best years away from you,” he said.

Instantly Comfortable

But if Olney lost a decade of his life to agoraphobia, a turn of events in 1978 provided him ample opportunity to make up for lost time. Having moved in the mid-1970s to Ventura, he was invited to discuss a book he had written about hockey on KVEN.

In a situation that would unnerve most people, he was instantly comfortable. “Something seemed to click,” he recalled.

Others noticed, too. One was the station’s manager, David Loe. “It was like a duck going into water,” Loe said. “He was able to be exactly himself on the radio. Only one out of a hundred can do that. Everyone else sounds just a little artificial.

“After years of going to cocktail parties,” Loe recalled, “I realized he was probably the best conversationalist I’d ever met. I’d never met someone who was so fun to talk to.”

After several more interviews and a stint as a substitute host, Olney was given his own show in 1983. Today, it’s the station’s second most popular show behind “The Dave and Bob Show.”

A typical day on the set of “The Ross Olney Show” would appear to be an agoraphobic’s nightmare. With seconds to air time on a recent morning, Olney flew into a glass-encased studio. He had nothing under control, nary a moment of the show planned.

‘Off-the-Cuff’

“I’m way behind, but that’s OK,” he confessed, plopping himself nonchalantly before a control board about as wide as the instrument panel on a 747.

“It’s kind of off-the-cuff,” he said. “I’ll fake my way into the show.”

Feverishly pulling cassettes of sound effects from their shelves like some kind of octopus, the wiry man with unruly silver hair had a show up and running. It wasn’t long before a string of listeners began calling to offer their opinions on everything from house plants to women in the military.

His social life appears to be no less hectic. Forever being called to act as host or emcee, he was planning that weekend to appear in a station-sponsored variety show. Olney was going to play the spoons.

None of this, he pointed out, would have been possible 17 years ago. He would have been too afraid of the occasional person peering into the studio, no less the uncertainty of a show without a script or, sometimes, a direction.

If anything, Olney acknowledges cheerfully, he errs on the other side.

“Now, whenever anyone asks me to do something, I say, ‘Great,’ ” he said. “You’ve got to do it. You can’t allow yourself to step back . . . to not do something because you’re afraid.”

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.