Antarctica’s Ice Shapes

- Share via

Icebergs really aren’t new. You’ve seen them before.

You’ve seen them at Luxor, where, with leonine heads, they guard the ancient temples of Egypt. You’ve seen them in Monument Valley where they rise in rusty red to shake fists at the Western sky.

You’ve seen them when the curtain goes up on the set of a Wagnerian opera, or when dawn breaks over the mosques of Istanbul, or a full moon spills onto the marble quarries of Carrara in northern Italy.

You’ve seen them when sailboats unfurl spinnakers in the sea off Perth, or when you gaze at the sloping shoulders of a Seth Thomas mantle clock.

That is, you’ve seen their shapes.

You have not really seen an iceberg, of course, until the sight makes you shiver, until all color is swallowed in a blaze of white and you hear an echo of fear from its depths. Even if that sound is the wind.

A White Lyre

You never forget your first iceberg, they say. That, I now know, is true. I awakened at 3:30 a.m. as our ship neared the spine of South Georgia, the snowy island gateway to Antarctica.

Through my cabin porthole I saw what looked like a white lyre tilted against the horizon, leaning there as if a musician had walked off and left it on stage.

It seemed small and distant and awesome. It was my first iceberg.

Later we landed on the pebbled shore at Husvik, one of the abandoned sites on South Georgia where Norwegians once ran whaling stations.

I marveled at the poise of the king penguins, their golden throats stretched toward the sky. I smiled at the swishy nature of the dove-gray seal pups.

Then I stared at the sea, where fleets of icebergs were gathered: a couple of old battleships and an aircraft carrier, an ocean liner festooned with flags, and the ghostly hulk of the Flying Dutchman that seemed ready to ram the lot.

I blinked at this glittering apparition but it did not disappear. And I remembered, with a shudder, that four-fifths of each berg is submerged.

Farther south we stepped onto the continent of Antarctica at a place called Bahia Esperanza, or Hope Bay. The morning was free of wind; the sea was as still as ice. The sun lapped at snow cliffs.

Some in our group strode off in search of fern fossils on rocky upthrusts; others settled near the shore to spend endless film on cavorting penguins, mostly Adelies with black-button eyes rimmed in white. The birds toppled slowly into the sea in a group dive that could have been a breaking wave.

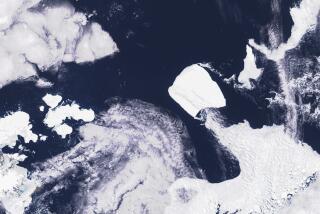

I stood on a high slope and pondered the sparkling expanse of Hope Bay. It seemed intensely familiar. Then I recognized it as the Chesapeake Bay, with its gridlock of super-tankers waiting to unload. Here the tankers were flat-topped icebergs, silhouettes a thousand feet long and 100 feet high.

Migrate to Warmer Seas

These giant tabular bergs are chunks of the ice shelf; they travel in westerly circles and generally migrate to warmer seas, where they break up. The average life is four years.

On the way back to the ship our rubber Zodiac boat swung out to circle a mansion in ice, a stunning berg that glowed with blue and green and violet light, as if part of a rainbow were trapped inside. It had cavernous rooms and pillars and balconies. It may have been 40 feet tall. We snapped photos and left.

As the next boat drew close for a view, a balcony ripped loose. Tons of ice hit the water and caused a wave that dumped eight people into the sea. At those near-freezing temperatures, survival is measured in minutes. Fortunately, the driver of an almost-empty boat saw the accident and raced in for a rescue. Everyone had worn life jackets. Nothing was lost but cameras.

In the end, Antarctica is as stingy as it is generous: It may give you days of wonder and glory, or serve up vast portions of fog. You may get to glide on quicksilver water in Paradise Bay, or be forced from its gates by rumbles of pack ice. You may get to see a snowy petrel or two, or you may search the ice floes in vain.

Change is the only constant at the bottom of the world. It amplifies the spirit of adventure, and helps separate a voyage to this pristine continent from any other journey in the world.

During a sundown lecture, as we headed north toward Cape Horn, a woman shouted “Good God!” We raced to starboard as a shadow fell across the lounge. It was a mighty iceberg, the whitest of whites, a wall of folded light.

I yearned to drop anchor and stay the night, to watch it glow pink with dawn.

But I was not the captain of my ship, so I could only touch my heart as we pulled away.

It was my last iceberg.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.