Zhao Ziyang: The Man Making China Modern

- Share via

SANTA BARBARA — The interesting commentary on our times is that the two political leaders working hardest for freer speech and freer markets are both communists--Mikhail S. Gorbachev and Zhao Ziyang. Both are people-minded, out-going optimists. Each needs every ounce of that optimism to bring his huge country in touch with economic realities, against the entrenched dead weight of two top-heavy, greedy and often corrupt party bureaucracies.

Lately Gorbachev’s fast political footwork--he is now president of the Soviet state as well as Communist Party boss--has grabbed most of the headlines. Zhao, working in the shadow of his mentor, China’s mentor, Deng Xiaoping, has kept a lower profile. But Zhao is fighting a tough battle to keep reforms moving ahead, in his case on two fronts.

China’s modernization program has enjoyed real successes over the past 10 years. The fresh air of a partly freed market has done great things for agriculture and created a new small-business economy.

But as modernization now moves into the big industrial centers, Zhao and his fellow reformers have to cope with conflicting interests: conservative Marxist party bosses, angry and frightened about the loss of economic control, versus the revived--and unruly--entrepreneurial instincts of the Chinese people.

Each new market reform carries with it a surge of new businesses, rising productivity and the kind of wheeling and dealing an average party boss is unable to control--unless doing the wheeling and dealing himself. Loosening of controls combined with rising demand and a growing money supply has brought China its first double-digit inflation in many decades. Meanwhile, there is no uniform system of laws and taxes to regulate increasingly heavy economic traffic. And conservative Marxist economists prevent the reformers from increasing interest rates or radically changing the old system of wastefully subsidized prices.

All this creates a vicious circle, Zhao standing right in the middle of it. As party general secretary, he has the job of setting national goals and then trying to energize 40 million members to support, not sabotage, them.

Zhao is a generation younger than Deng and a confirmed political realist--his reforming talents in Sichuan Province became a model for all of China. Zhao realizes that hesitant half-measures will not make China’s economy healthy. Unfortunately, the inevitable dislocations of going to a market economy are regarded by many party members as an argument for stopping liberalization and going back to the same economic dictatorship that was responsible for China’s retarded status in the first place.

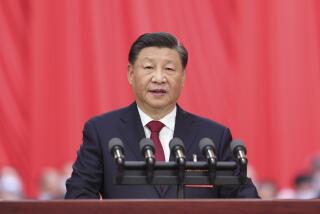

Last month, I interviewed Zhao, the first time in a long time that he had talked to a foreign journalist in Beijing about economic problems.

Beijing’s sequestered foreign community, in fact, is where rumors generally have to substitute for press briefings; informed gossip was lately suggesting that the general secretary was on his way out.

I found no evidence of that. For one thing, no Chinese public figure has the capacity or the drive to replace Zhao. He has become as much a symbol of modernization as Deng himself. And he is far more capable of carrying it out to its logical conclusions, despite the foot-dragging of his colleagues.

I had visited with Zhao in 1984, when he was still prime minister. He had the same jaunty manner as before--although his hair has whitened considerably since then. Wearing a natty, well-cut light suit, sipping a beer and making a few jokes as we went along, he offered, in his characteristically frank way, a progress report.

“We met with many new problems,” he admitted, “problems which have not been encountered by other socialist countries. We in China have solved the problem of our eventual goal: Our country is a socialist country, but it’s socialist on the basis of a planned-commodity economy. The state should regulate the market but enterprises should at the same time guide on the market. While public ownership should still play a predominant role we should at the same time develop many forms of ownerships.

“In 1984, when you came to China, we only mentioned individual ownership. Now we have expressly allowed private ownership--that means the right to hire workers. Our constitution has been changed to permit the private economy to exist in China . . . . But we are not going the way of privatization, as tried in Western and some of the developing countries.”

Zhao explained that the bulk of China’s industry should remain publicly owned but that industry management should be virtually autonomous--freed from political control. He continued: “The relationship between the state and entrepreneurs is a kind of contract--like the contract-responsibility system we set up in the countryside . . . . The managers should have the right to operate their properties and in a legal sense have the right to dispose of them.”

Zhao admits problems: “The old system has been greatly weakened, but the new system has not been fully established, so we have contradictions and frictions. . . . We have a market, but it is not well-grounded. We have a competitive mechanism, but it lacks order and regulation . . . . We still lack a healthy and sound series of laws to govern our market. As a result, we have inflation and turmoil in the flow of goods and money.”

Despite inflation, Zhao has continued to hammer at China’s biggest problem, the removal of price controls: “We must place price reform on our agenda as an important item . . . . The success or failure of our price reform depends on the economic performance of our enterprises, which in turn hinges on the success or failure of enterprise reform.” In other words, letting prices find their own level will not work unless more of China’s enterprises start basing themselves on productivity, not politics.

Collective party decision-making, in which Zhao played a major if perhaps reluctant role, has in fact come down on the side of caution. The word has gone out to go slow on construction, go slow on capital investment. Beware of economic overheating and, above all, avoid freeing prices, which in the short term would cause a great deal of hardship to wage-earners, especially intellectuals and bureaucrats on fixed salaries. Zhao conceded the inequity: “That the income of mental workers is lower than that of manual workers is irrational. This must be changed . . . but it will take several years’ time.”

He also, more obliquely, criticized rampant corruption, profiteering and the “need to make party and government workers honest.”

Zhao stuck to his message that hope lies in an increase of freedom and an increase of competition. He seemed even more confident about his goals and priorities than he did four years ago. Yet government and party are where he faces his greatest problems.

For all the lateness of Soviet economic reforms--and their lack of visible success thus far--Gorbachev has apparently succeeded in forcing through some real political reforms. Economically speaking, Zhao is way ahead; improvement in China’s countryside has been spectacular. And even hard-pressed city dwellers have enjoyed freedoms and creature comforts that were inconceivable in the days of Maoist repression.

Yet Zhao has yet to crack the encrusted party elders. Their conventional wisdom, weighed down with Marxist dogma, makes the pace of economic modernization harder to keep up the closer it gets to its goal. That’s because their own political lives are threatened. Zhao knows this full well: “Where we are vigorously promoting reform and an open policy, it is very hard to draw a demarcation line between what would be economic work and what would be party work.” In drawing such lines, he could certainly use a bit of Gorbachev’s political success.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.