‘Papa Bear’ Gerlach ‘Lost a Lot of Good Friends’ : For Marine Commander, Scars of Blast Remain

- Share via

FAIRFAX, Va. — On the paneled wall of Larry Gerlach’s study, a red-matted shadowbox displays the 20 medals, including two Purple Hearts, that he won during 21 years in the Marine Corps.

On the floor below was a red wheelchair and crutches that are souvenirs of his last posting in Beirut.

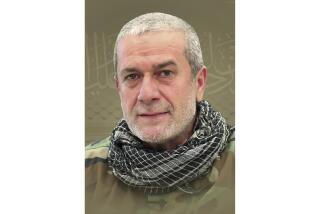

Gerlach, nicknamed “Papa Bear” by his troops and peers because of his hulking frame and gentle nature, was the battalion commander in Beirut on Oct. 23, 1983. Today he has only partial use of his arms and legs.

Blown out of his bed and across the surrounding field by the explosion “like a sack of potatoes,” in the words of another survivor, Gerlach spent the next 11 months in the hospital.

“The ‘$6-Million Man’ has nothing over me,” he joked recently, referring to the surgery and the bits and pieces stitched into his body over the past five years.

“But the physical scars have healed more completely than the mental scars,” he added. “I think about the tragedy every day. I lost a lot of good friends.”

He and his wife, Patty, still have the list of the 241 servicemen killed that she showed him when, seven weeks after the bombing, doctors finally said he was alert and strong enough to be told what had happened. Until then, he had thought an artillery shell had hit his corner of the compound and that he had been among a few casualties.

Retired from the Marines because of his disability, the former lieutenant colonel is more philosophical than bitter.

“I have yet to have someone tell me what we could have done differently to have prevented it,” he said. “We were in the second-highest security state. If we’d been in a higher state, there would have been even more killed because we would have brought them down from the higher floors.”

Gerlach was one of the few survivors not on the top floor or the roof; many of the Marines on lower floors were crushed to death. A commission appointed by then-Defense Secretary Caspar W. Weinberger subsequently concluded that the decision to billet so many Marines--about one-quarter of the U.S. force assigned to Lebanon to monitor the withdrawal of foreign troops--in a single structure contributed to the catastrophic loss of life.

Gerlach, as the battalion commander, received a “letter of instruction,” a non-punitive form of directive, from the Marine Corps. But previous Marine commanders in Beirut as well as superiors from the Pentagon and the U.S. European Command who visited Beirut had all approved the arrangement.

Gerlach said the controversial order to the Marines that they leave their guns unloaded did not necessarily contribute to the disaster. “By that point it was already too late,” he said. “The only way to have avoided the bombing was not to have been there. We were simply a tripwire in Beirut.”

Unlike many of the survivors, who told Mideast correspondents at the time that they felt they had been victims of U.S. policy as well as Shia Muslim fanaticism, Gerlach refuses to complain.

“It wasn’t my policy in Vietnam or in Beirut, but I’ll support it to this day,” he said. “The military should not do anything but support the policy that’s in place.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.