‘Morality Crisis’ Prods Some Schools to Start Teaching Values Again

- Share via

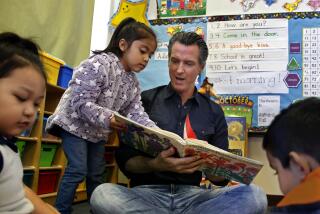

The first-graders in Sharon Miller’s class at Walt Disney School in San Ramon, Calif., listen attentively to the story of Amos the Mouse who capsizes in the ocean. Lonely and tired, Amos comes across Boris the Whale and climbs aboard. Surprisingly, the two creatures discover they have something in common--both are mammals--and they learn to get along. Boris agrees to warn the tiny mouse before he dives and Amos uses “dive time” to take a swim.

The story is part of a pilot program designed to develop character in children. For years, parents and educators in this upper-middle-class community 35 miles east of San Francisco have been struggling with a weighty question: How to go beyond academics and raise “good kids” imbued with such qualities as concern for others, helpfulness, consideration, generosity, understanding and a sense of community?

Once a Controversial Agenda

Responding to that question, San Ramon and a growing number of other school districts are opting for what was, in the not-too-distant past, a highly controversial agenda: Teaching values in public schools.

“We’ve found a great deal of consensus on this. We don’t want to produce children who can only score high on (academic) tests. Everyone wants their child to grow up to be helpful and responsible, to be good citizens. No one wants to see his child become an immoral, scheming, rich drug dealer. Even gangsters want their children to be moral,” said William Streshly, superintendent of San Ramon Valley Unified Schools.

Some communities are motivated by headlines pointing to a morality crisis, such as recent Wall Street and Pentagon scandals and widespread drug abuse. Others, noting that today’s families spend little time together, think schools must go beyond the three Rs and play a greater role in shaping children. And since research indicates the most powerful influence in raising a caring child is an early, parental role model, most efforts seek to involve mom and dad in curricula that include stories, discussions and group activities.

Three or four decades ago, schools routinely sought to inculcate values. However, due to pressure to maintain separation between church and state, “Schools grew concerned that teachers were teaching religious values and backed away,” said Martharose Laffey, assistant executive director of the National School Boards Assn.

Today’s approach painstakingly avoids religion. Described variously as “character development,” “values education,” or “pro-social development,” the programs differ. But all “are trying to help young people formulate their characters and be productive citizens,” Laffey said.

Idea Is Spreading

Although the movement is small, it is gathering momentum:

--Recently New Jersey Gov. Thomas H. Kean directed Commissioner of Education Saul Cooperman to initiate a character-development program for all of that state’s school children.

--Next semester, third graders at 10 Los Angeles Unified School District schools have been targeted for “efficacy training” developed by the Efficacy Institute of Detroit, Mich. “The cornerstone is teaching kids that they are responsible for acting and interacting, responsible for their environment and their community,” said Carolyn Webb de Macias, area vice president for Pacific Bell, which is picking up half the tab for teacher training.

--Alarmed by studies that showed a serious communication gap between parents and children, the school district in Baltimore County, Md., formed a values study group including disparate viewpoints of a Fundamentalist minister and the American Civil Liberties Union.

Kids Have Own Values

“Whether because of television or the greater independence of kids today, it became clear kids were making up their own values, based on TV, rock music, the way their peers were perceiving values,” said Associate Superintendent Mary Ellen Saterlie. “At one point, we realized that democracy can’t survive if values aren’t transferred from one generation to the next.”

--The Calabasas-based Center for Civic Education, established by the State Bar of California, has a similar concern. Through its Law in a Free Society Project, the center developed curricula for kindergarten through 12th grades, explaining concepts such as authority, privacy, justice, responsibility, freedom, diversity, property and participation.

“John Locke and amendments to the U.S. Constitution don’t mean much to a young child. But even kids in kindergarten can understand why there is a need for authority, what would happen on the playground if there were no rules, and what makes a good rule,” said program associate Mike Leong.

Cultural Resistance

Why has it taken so long for the pendulum to swing back toward social learning in public schools? In addition to the issue of separation of church and state, there is another kind of resistance, say observers.

“Our entire culture is afraid of teaching children about behavior. A large part of the adult population isn’t oriented toward believing that behavior is something that can be understood,” said Marian Radke-Yarrow, chief of the Laboratory of Developmental Psychology at the National Institute of Mental Health.

Barbara Smith, assistant superintendent of elementary instruction for the Los Angeles Unified School District, takes issue with any program with a name such as “Character Development.”

“It really sounds holier-than-thou,” she said. “I would say children have a great deal of character and when their behavior is different from what is socially acceptable, it is because, from the child’s perspective, other priorities have to be addressed,” she said.

Nothing New Here

In fact, educators say a good deal is known about fostering caring, responsible development in children.

“None of the things we are doing are new revelations. What is new is that we are bringing together academic and social learning so they happen simultaneously,” said Eric Schaps, director of the Developmental Studies Center, an educational research group that designed the San Ramon program.

Prior to implementing the Child Development Project at three of the district’s schools, researchers asked parents to make a list of 20 characteristics that can be taught to children. Unanimously, parents selected sensitivity to others, helpfulness, cooperation, getting along with others and understanding society’s ethics. Without changing the academic curriculum, the program incorporated the parents’ top five priorities.

Rather than trying to get children to perform well or behave through threats of punishment or promises of reward, a key element is trying to teach children the value of learning rules and behaving ethically.

“What you are aiming for,” said Nancy Eisenberg, a psychologist at Arizona State University in Tempe, “is to get kids to internalize and empathize or do the right thing on their own, not just when adults are around.”

The San Ramon effort, emanating throughout the curriculum, enlists the help of teachers, students and parents. “This is not some cutesy add-on, where we say, ‘For 10 minutes, Monday, Wednesday and Friday, we’re going to learn to be good Boy Scouts,’ ” said Superintendent Streshly.

At the beginning of the year, children help write the rules: “We want our classroom to be a colorful, clean, beautiful place where people talk calmly and help others. We listen when others talk. We try to do nice things for others,” according to the statement drawn by Sue Smith’s first-grade class at Rancho Romero school in nearby Alamo. Generally, such credos translate into prohibitions on hitting, name-calling, or even excluding a child from a group activity.

To foster skills such as listening, showing respect and working together, children take part in so-called “cooperative learning” projects. Group members may be assigned roles, such as the “recorder” who takes notes, the “facilitator,” who moderates, and the “reader,” who reads the problem.

Cultural Exposures

Teachers rely heavily on literature to help children understand the human condition. During the year, the district’s primarily white children were exposed to a Japanese lunch, celebration of Korean holidays and visits from other minority groups. Students also listen to a handicapped child tell what it feels like to be teased, resulting in a dramatic drop-off in playground incidents.

In another move, designed to put an end to bullying, older and younger students become “buddies,” with older kids helping with art, language or math. In May, second-graders show their younger charges how to walk to the cafeteria and move through lines.

The program also seeks to foster concern for the local and global community. Anonymously, schools adopt a needy family. Students collect toys, clothing and raise money for holiday meals.

The parent-education component brought changes to the home of Michelle and Barry Brynjulson and sons Brock, 11, and Jesse, 14. “We’ve seen a remarkable difference, in part because of different parenting,” Michelle Brynjulson said.

After deciding the boys needed to feel more like active family members, the couple began listening to their sons’ viewpoints when establishing rules. To reinforce the message, the boys do their share around the house. “For example, we deliberately don’t hire a gardener, because we want the kids to get the idea that we all do our part. They also cook one meal a week and take out the trash,” Michelle Brynjulson added.

Neighborhood spats have fallen off markedly, she added. “I overheard an encounter where a neighbor’s child didn’t want to play a game with my son. Instead of my child saying, ‘Fine, I’ll go find someone else,’ I heard my son ask, ‘Why don’t you want to play?’ They established some new rules and were able to play together. That never would have happened in the old days.”

The fact that they are helping their children develop standards pleases the Brynjulsons. Indeed, experts agree that kids aren’t born with an innate sense of values.

“We want kids to have good values, but we don’t focus on how to teach them. Going to church isn’t enough. You have to integrate these values into your life,” said Don Fleming, a West Los Angeles psychotherapist.

Fleming and others believe that at a very young age, children note how parents relate to one another, to them and to the rest of the world. “When a child sees a parent interacting with people in non-caring ways through anger, irritation, frustration and aggression, that is what a child learns,” he said.

Not that parents need to be perfect all the time. “But if a parent loses control, what you should do is go back to your child and take responsibility for your inappropriate behavior. This can be the beginning of a character-building experience. Say, ‘Mommy got out of control. I really shouldn’t scream at you and I’m sorry,’ ” he said.

Parents Can Help

Parents can also effectively use incidents to interpret and suggest values. “If you are sitting in a restaurant you can observe. You can say, ‘That really wasn’t a nice way for that man to talk to his wife when he yelled at her across the table. Mom and dad try not to do that,’ or, ‘Did you see how nicely that kid shared his toy? Wasn’t that nice of him?’ Or, ‘Did you see how nice it was when that little girl gave her brother a toy? That was a very nice thing to do.’ What you are doing is making sensitive comments about values,” Fleming said.

One of the best ways to demonstrate an adult’s values is to involve children in community efforts to help animals or people. In an impressive family effort, Fleming observed parents who, once a month, took their young children to a day care center for children less fortunate. The family not only brought toys but encouraged their children to stay and play.

“When the outing was over these parents said to their children, ‘See, the children here are very much like you. We are very lucky to have all the things we do. We should always be kind to people, even if they don’t have as much as we do.’ ” Over time, the family visited various community agencies for people in need. By age 6, Fleming said, the couple’s children understood the concept and expressed concern.

In the Baltimore County School District, parental input was the source of inspiration, according to Associate Superintendent Saterlie. After forming a values study group, the district panel asked each school to draft its own plan for teaching values, with some novel results.

In the southeastern part of the district, which was experiencing high unemployment among steel workers, parents chose to focus on self-esteem and self-worth. However, at Pikesville High School, where students engaged in fierce competition for good grades, parents directed efforts to issues of academic honesty, such as cheating, plagiarism and filling out college applications.

To those who argue that teaching values properly belongs in the home, Sylvia Kendzior of the Child Development Project responds: “Children spend most of their waking hours at school. We are teaching children the things necessary to make democracy work, such as empathy, understanding diversity, appreciation and respect, and a sense of ‘we.’ These things need to be happening at school, regardless of what is happening in the rest of society.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.