At CSUN, the Very Model of a Man of Genius--da Vinci

- Share via

The inventions sketched by Leonardo da Vinci in more than 8,000 pages of personal notes testify to the brilliance of the 15th-Century painter, who envisioned such possibilities as helicopters, automobiles, hydraulics and robots.

But wind up, crank, push or pump one of the working models that go on exhibit Monday at Cal State Northridge and the true genius of the Renaissance man comes to life.

“At first you see them as inert, immobile objects,” said Donald Strong, a professor of art history at CSUN. “But when his machines are working, they are, in fact, living machines.”

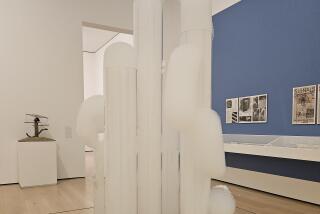

Twenty-four replicas of the devices, including a paddle-wheel ship, odometer, drill press, pile driver and parachute, will be at CSUN’s Fine Arts Gallery through April 14. The models, on loan from a collection begun in 1951 by IBM, are all “hands-on” exhibits, made from wood and brass, standing several feet tall.

Grab the crank of a scaling ladder and spin the large, toothed gear until all the sections are extended. Da Vinci was thinking in terms of scaling the wall of an enemy fortress, but the device clearly predates modern firefighting equipment.

Turn the handle on one of his many gear systems--machines more theoretical than practical in his day--and see how da Vinci used several cogs to simulate what today might be called a variable-speed transmission.

And don’t forget to spin the wheels on the military tank, an armored capsule intended for carrying heavy firepower and to be driven from within by men with cranks.

“This is all movement with a purpose,” said Strong, who will lecture about the devices at 10 a.m. March 27 in the Fine Arts Gallery. “He believed he had the power to design something that had a living presence because it obeyed the same laws of operation as anything created by nature itself. In Leonardo’s mind, man created on a par with nature.”

Of course, da Vinci was not the only man of his day weighing the heady ideas that made the 15th Century one of the most colorful, vital periods in history. But what made da Vinci unique, say scholars, was his extraordinary gift for synthesis, visualizing the relationships between art, medicine, music, engineering and the forces of nature.

Born in 1452 near Florence, Italy, da Vinci was the illegitimate son of a notary and, as such, was not permitted to attend the local university. Instead, he studied painting and gained the artistic perspective that allowed him to record with such precision the wonders of the world he lived in.

He dissected corpses to learn human anatomy, observed birds to design flying machines, studied architecture to make maps, and mastered optics and color so that his paintings, such as the “Mona Lisa,” radiate with warmth and intensity.

“For him, art and science were the same, and their purpose was to lead to truth, to an understanding of the secrets of man and of the universe,” writes Richard McLanathan in the IBM catalogue that accompanies the exhibit.

Perhaps no better example of that quest can be found than in da Vinci’s notebooks, which by the time he died in 1519 were filled with inventions ranging from the practical to the fantastic, from the gruesome to the sublime.

The modern models are the work of Roberto Guatelli, an engineer from Milan who was commissioned in the late 1930s by Benito Mussolini to replicate 156 of the devices. All of them were destroyed in bombing raids during World War II.

But after the war, Guatelli came to the United States, where he built another 56 models for a show that opened at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in 1950. The following year, IBM hired Guatelli to continue making the models, and for the last four decades they have been on almost continual tour in this country and around the world.

“I feel like he is my dead grandfather,” Guatelli once said of da Vinci. “If he were here, he would chase me around the block yelling, ‘What are you doing to my work?’ ”

“Leonardo da Vinci: The Inventions” will be on display Monday through April 14 at the Fine Arts Gallery at Cal State Northridge, 18111 Nordhoff St. Gallery hours are noon to 4 p.m. Mondays, 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. Tuesdays through Fridays, 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. March 18 and April 1 and 8, and noon to 4 p.m. April 9. Admission is free.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.