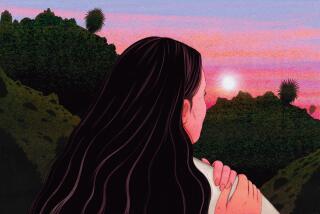

Waiting had become almost second nature to Ara . . . .

- Share via

Ara Sevanian, a slight, gray-haired man of elegant features, sat patiently in the Burbank Airport lounge, occasionally asking the same polite question of the friends and relatives gathered around him.

“It’s 4:30,” someone answered.

Flight 2784 from San Francisco was behind schedule.

Ara waited.

After nearly 50 years of waiting to see his brother Hrair, perhaps it was only fitting that the flight that was bringing Hrair on the final leg of his journey to the San Fernando Valley was late.

Waiting had become almost second nature to Ara, a 73-year-old Armenian-born composer and musician who was separated from his country and family in the chaos of World War II. At Gate B1 at Burbank Airport, where Ara and a dozen relatives and friends gathered Friday to greet Hrair, Ara’s long wait would end.

For decades Ara had asked the Soviet government to grant his mother and father permission to visit him in the United States. And for decades, the petitions were denied--Ara’s parents died before he could see them again.

But then a few weeks ago, Hrair, now 66, was finally granted a passport and visa. On Friday, the two brothers would see each other for the first time since they were teen-agers growing up among the medieval churches and wide, tree-lined boulevards of Yerevan, the capital of Soviet Armenia.

The last few minutes of separation were a time to reflect on the improbable events of their lives, since he last saw Hrair chasing a Soviet Army truck carrying Ara into World War II in the desperate days shortly after the Germans invaded the Soviet Union.

Ara believes that it was only through a bureaucratic mix-up that he was even drafted into the Red Army in 1941.

Before the war, Ara was recognized as a master of the kanoon , an Armenian harp-like instrument he played before Josef Stalin and other Soviet leaders at an Armenian cultural festival in Moscow’s Bolshoi Theater in 1939.

Stalin was sufficiently impressed by Ara’s mastery of the instrument to invite him to play a command performance at the Kremlin. “When he smiled, his mustache curled up,” Ara recalled. At the end of the performance, Ara was granted the Order of the Red Flag, the Soviet Union’s second-highest honor.

Ara said the award should have made him exempt from military service. But two days after Hitler invaded the Soviet Union in 1941, he was drafted into the Red Army. An apologetic bureaucrat acknowledged the mistake, but said there was nothing he could do.

As Ara sat with other conscripts in the back of an army truck, waiting to be dispatched to the front, Hrair appeared in the crowd of relatives and friends who had come to bid the soldiers farewell.

“He was yelling, ‘Ara, go home. I fight for you!’ ” Ara said. At 17, however, Hrair was too young to enlist in Ara’s place.

When the truck pulled away, Hrair followed, running behind the truck until it sped away on the dirt road. “The truck started going fast, everything turned to dust, and that’s the last I saw of him,” Ara said.

With other captured Soviet soldiers, Ara nearly starved to death in a German concentration camp near Berlin. He was left for dead at the edge of a mass grave until an Armenian prisoner on the burial detail recognized him. The prisoner remarked to a German officer in charge that one of the corpses was that of a well-known musician in his native land. The officer, a violinist before the war, checked to see if he was dead. Finding that Ara was only unconscious, he told the others not to bury him.

The officer later let Ara eat food from the German guards’ kitchen, built up his strength and got him released to play concerts in Berlin. Ara had escaped death, but the German officer’s act of kindness had unforeseen consequences.

Because of his release from the prison camp, Ara said, he was classified as a deserter by the Red Army. Fearing punishment if he returned to the Soviet Union, he settled in Germany after the war and eventually made his way to the United States.

While his brother became a carpenter and raised a family in Armenia, Ara settled in Van Nuys. He composed music in his free time, earning his living by running Ara’s Armenian Hamburgers, a small stand on Van Nuys Boulevard. One of his compositions--”Protest,” inspired by the prejudice he encountered as an Armenian in Nazi Germany--was performed by the Los Angeles Philharmonic.

For years, the two families communicated through correspondence and occasional long-distance phone calls. As soon as they could write, Ara’s children--Alex and Deeana--sent letters to their uncle. Hrair sent back yellowing clippings from Pravda detailing Ara’s prewar musical accomplishments.

After Hrair got his passport, he took a circuitous route to the Valley, flying first to Moscow, then to Mexico City and finally to San Francisco, his last stop before Burbank.

Hrair was crying when he telephoned his brother from San Francisco the morning he was to leave on the final leg of his journey. “I said to him, ‘Don’t cry when you see me. Be a big man,’ ” Ara said, making a fist for emphasis.

When Hrair’s flight arrived, it was Ara’s daughter Deeana who spotted him first. Although she had never seen her uncle, among the passengers descending to the runway, she sighted a man carrying a small shopping bag who bore an uncanny resemblance to her father.

“There he is . . . the man that looks lost,” Deeana said, pointing to a slender man with her father’s Roman nose and high brow.

Hrair caught sight of his brother. “Ara!” he cried out, dropping his bag and running a few steps until the two fell into an embrace. Both wept.

For the moment, the men could only repeat a single word.

“Finally.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.