The Swoon of Blasphemy

- Share via

by Imam Ruhollah Khomeini

I have become imprisoned, O beloved, by the mole on your lip! I saw your ailing eyes and became ill through love. Delivered from self, I beat the drum of “I am the Real!” Like Hallaj, I became a customer for the top of the gallows. Heartache for the beloved has thrown so many sparks into my soul That I have been driven to despair and become the talk of the bazaar! Open the door of the tavern and let us go there day and night, For I am sick and tired of the mosque and seminary. I have torn off the garb of asceticism and hypocrisy, Putting on the cloak of the tavern-haunting shaykh and becoming aware. The city preacher has so tormented me with his advice That I have sought aid from the breath of the wine-drenched profligate. Leave me alone to remember the idol-temple, I who have been awakened by the hand of the tavern’s idol.

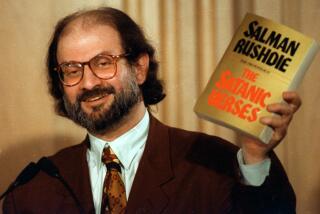

The poem above appeared on June 21, several weeks after Imam Khomeini’s death, in an Iranian newspaper, Kayhan. Translated into English by William Chittick, it appears in the Sept. 4 issue of the New Republic. As Khushwant Singh says in the adjoining essay on Salman Rushdie, there is a long Muslim tradition of mysticism using the tavern as a literary vehicle. Khomeini continues this tradition in an utterly conventional way.

Hallaj, mentioned in the fourth line, is Hussein ibn Mansour al-Hallaj (857-922), a Persian mystic who was also a writer and something of a showman. The most famous of many statements in which he identified himself with God is the line, spoken in Arabic, Ana al-Haqq, “I am the Truth,” or as in the translation above, “I am the Real.” Though executed for heresy and blasphemy, Hallaj has nonetheless been remembered and routinely quoted even by Muslims as orthodox as Imam Khomeini.

The great heretical mystic was, in his way, the Salman Rushdie of his day. Once, hearing a friend recite from the Qur’an, he said: “I could utter such things as that myself,” a claim comparable to Rushdie’s suggestion in “The Satanic Verses” that religious and literary inspiration are identical. Hallaj was thought by some to be mad. Rushdie’s character Mahound seems mad during the revelation scenes of “The Satanic Verses.”

According to a report in the New York Times, Khomeini’s poem was made available by his son, Hojatolislam Ahmed Khomeini. Its publication may then be part of a posthumous elevation of the late religious leader to the status of mystic. During his lifetime, Khomeini was a theological authority or ayatollah and, after 1979, the Imam or vicar of Prophet Muhammad; he was not known as a mystic. Did Imam Khomeini condemn Rushdie to death in part because the writer was enacting proscribed mystical aspirations that, reportedly, were a part of Khomeini’s youth? Did he recognize in the religion-obsessed novelist, in other words, not just a blasphemer but also, by intent, a rival? Or is the poem simply a school exercise turned to hagiographic purposes?

Poem translation (excluding only the title) 1989, William Chittick. Reprinted by permission of The New Republic.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.