Employers Gain the Most From Boost in Jobless Benefits

- Share via

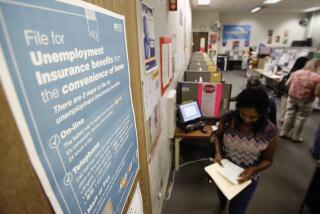

Out-of-work Americans don’t get much assistance these days at either the national or state level.

Nothing is being done in Washington to provide the help that they need to tide them over their rough jobless times.

That leaves the burden on the states that, by law, determine the amount of unemployment benefits, and they all fall far short of the goal set by a 1980 blue-ribbon National Commission on Unemployment.

Even when states do raise benefits, as California has finally done for the first time since 1983, the results are meager, at best.

The moderately liberal California Legislature, controlled by Democrats, have passed bills to increase unemployment benefits five times since conservative Republican Gov. George Deukmejian took office seven years ago. He vetoed all but the latest one, which he signed Oct. 1.

Despite California’s wealth, our benefits are among the nation’s lowest; only four states provide less. The commission said jobless benefits should be enough to replace at least half of the average worker’s weekly pay in each state. Instead, the average state provides only 38% of the average weekly wage, and California’s unemployed get only 26%.

The more that you earn while working, the higher your weekly benefit will be if you lose your job. But the most an unemployed worker in California can get now is $166 a week, hardly enough for a middle-income person to pay the mortgage or rent, much less for the other necessities of life. And the average benefit is only $122.

Pressure for raising the inadequate benefits has come over the years primarily from the California AFL-CIO. The labor federation’s executive secretary, John F. Henning, claims a victory because Deukmejian has not only approved a hike in unemployment benefits but he has also OKd increases in workers compensation and disability benefits for the first time since 1983.

All of the increases are small. But then, perhaps they are more than might be expected, considering the unbending opposition to meaningful increases by the business community and its ally, Deukmejian, with his veto power.

The maximum jobless benefit in California will go to $190 a week next January, a boost of just 14.5%. That’s not nearly enough since consumer prices have more than doubled since benefits were last raised.

There will be further increases, and by 1992, maximum benefits will hit $230 a week, which wouldn’t be terrible if, by some miracle, we have a zero inflation rate between now and then.

Small as the unemployment benefit boosts are, however, they will cost about $262 million, and California employers this year are already paying $1.9 billion to finance the unemployment insurance system.

That sounds like, and is, a lot of money. But don’t cry for the state’s 800,000 employers. They now pay less for jobless insurance than employers in most other states, and things are going to get even better for them.

Employers will actually pay more than $180 million less in unemployment insurance taxes during each of the next two years than they now pay. That is a 9.5% cut in their present taxes, and they can expect to continue paying lower taxes in the future.

How can workers benefits go up and employer taxes, which pay for the benefits, go down at the same time?

Well, for starters, the jobless themselves will take care of $35 million of the tax cut that the employers will enjoy because an estimated 40,000 of the unemployed will lose their benefits under new, stricter eligibility rules adopted along with the benefit hike.

While California jobless benefits trail behind those of most other states, the state does have less restrictive eligibility rules than most of them. That means that it has been relatively easy for California workers to qualify for benefits.

Nationally, fewer than one out of every three officially unemployed workers are able to get jobless benefits because of increasingly tight eligibility restrictions. That ties 1987’s all-time low, and California’s record is much better than that.

But the measure that Deukmejian has just signed tightens this state’s restrictions, and that, in turn, will help save money for employers because fewer workers will be eligible for benefits.

For example, starting Jan. 1, a worker must earn at least $1,200 in one quarter to qualify for benefits instead of $1,200 in an entire year, as the law now requires. The tighter restriction will affect mostly very low-wage, part-time workers who don’t earn enough to entitle them to any benefits if they lose their jobs.

And more savings will come for employers from a reduction that the new legislation makes in their basic unemployment insurance tax.

The lawmakers decided that the $5 billion California has in its unemployment reserve fund is more than enough to pay benefits to jobless workers even if a recession significantly increases their numbers.

The reserve may be adequate, although it is no more than other states have for their size. But in any case, it certainly appears to be an enormous sum, and hence, politically, too much for the Legislature to hold back just in case of a serious recession.

You see, employers went along with the relatively small hike in benefits for the jobless because by doing so they get a nice reduction in the money that they must pay to support the system.

The seven-year battle over jobless pay, workers compensation and disability benefits is over for now, at least in California. But since the benefit increases are so small, it is hard to claim, as some do, that a major victory has been won for workers.

Still, as some wag might conclude, it is surely better for workers than another punch in the nose, which they have been getting since 1983.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.