30 Years After His Death, Fans Still Clamor for Music of the ‘New Caruso’

- Share via

PHILADELPHIA — Thirty years have passed since the death of Mario Lanza, the curly haired movie star with the booming tenor voice that earned him the nickname “the new Caruso.”

But memories of Lanza live on--in his fan clubs, in his records, which still sell briskly, and especially in his old neighborhood, the Little Italy section of South Philadelphia, where opera once was as popular as baseball was in Brooklyn.

Lanza was just 38 when he died of a heart attack on Oct. 7, 1959, 10 years after the opening of the first of his seven movies.

“But you see, it didn’t really end there,” said Nicholas Petrella, who owned a corner record store in Lanza’s old neighborhood. He did $38 a day in business until Lanza came home a star. That day, Petrella did more than $4,000.

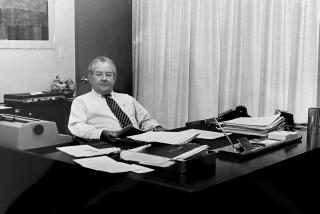

Today, he is president of the Mario Lanza Institute and Museum, on the third floor of the Settlement Music School where Lanza studied violin and piano as a boy. “The voice that he had and his spirit still live today, right here in Philadelphia, all over the world,” Petrella said.

The only son of immigrant parents, Lanza was born Alfredo Arnold Cocozza in 1921, the same year opera lovers mourned Caruso’s passing. A member of his old neighborhood gang recalled “Freddie” Cocozza as “loud and raucous,” a superb athlete who loved the summer beaches of Wildwood, N.J.

Lanza grew up listening to the family collection of Caruso records. His voice began to develop and one day he sang along with the great tenor’s recording of “Vesti la Giubba.”

“To my utter amazement, I found I could reach the high notes with comparative ease. I was overjoyed. My heart was bursting,” Lanza said years later.

His mother had wanted to be an opera singer, a career denied proper young ladies. So Maria Lanza married instead.

According to her sisters, Julia Alioto and Hilda Lanza, it was MAria who encouraged her son to choose Hollywood over the opera. He thanked her by adopting her maiden name and the masculine form of her first name.

The singer had little formal training. Enrico Rosatti, a well-known teacher of the old school, once told Lanza: “No one can teach you to sing, my boy. You had the greatest teacher of all--God.”

At his grandfather’s summer home in Wildwood, however, he took lessons from a blind man named Paul Bosco, godfather to the Lanza brood.

Years later, Hollywood hype held that Lanza had been a truck driver and piano mover prior to his movie career. “He never worked like that a day in his life,” said his uncle, Arnold Lanza. But he did pose as a piano mover to get into the Philadelphia Academy of Music for an impromptu audition. The ruse worked; conductor Serge Koussevitsky took him to the Berkshire Music Festival.

World War II made him a private in the Army Air Corps in Texas. A bad eye kept him away from combat. He discovered Special Services and decided to try for the “Winged Victory” show. His throat was sore the day of the audition so he ripped the label from a Caruso record and submitted it as his own.

Also in the show was actor Bert Hicks, who introduced Lanza to his sister, Betty. Mario and Betty later married and had four children.

Discharged, back in New York, the singer met RCA vice president Jim Murray and signed a record contract with the same company that had recorded Caruso. Lanza also later hired Caruso’s old agent. Ultimately, he decided that he could reach many more through films than from the stage, and he performed only one opera, “Madame Butterfly,” with the Grand Opera in New Orleans.

In Hollywood, Terry Robinson was given the job of helping Lanza trim pounds for the camera. He also became a close friend; when Lanza’s wife died in March of 1960, Robinson and his late friend’s parents raised their four children.

“There are so many things to remember,” Robinson said. “The nights when Mario would take one of the girls and I would take the other. Then we would go up the stairs to their bedrooms as he sang to them. The nights he was out and the maid would play one of his records so they would sleep. A $50 tip to a waitress and picking up the lunch checks of those who recognized him.”

In 1950, Lanza filmed “The Toast of New Orleans” followed in 1951 by the box office smash “The Great Caruso,” Lanza’s favorite. He threw himself into the role, even gaining weight to match the accounts of Caruso’s growing bulk.

“For me, the film . . . was an unbelievable dream come true,” he said.

Two more movies followed, “Because You’re Mine” and “Serenade.” He then got into a fight with MGM over “The Student Prince” and was replaced. The movie was a flop, although the soundtrack featuring Lanza was an album smash. But concerts were canceled due to health and other problems, his managers allowed him to sink into debt and friends turned away from him.

He and his family fled to Italy in 1957, where he made two more movies, “The Hills of Rome” and “For the First Time.” Concert tours sold out as quickly as they were announced.

At the time of his death, Lanza’s comeback was well under way. His body lay in state in Philadelphia, and thousands filed past, holding the funeral home open until 3 a.m. Antoinette Marzano, 71, an old family friend, collapsed and died after passing the casket.

Lanza was buried in Los Angeles, near the tomb of comic Lou Costello.

Today, 30 years later, Lanza’s legacy includes scholarships for young singers, financed by an annual ball held each November.

His records also survive, and RCA continues to sell them, updating them now into compact disks. They yield about $100,000 a year in royalties.

Mario Lanza fan clubs are still active in Orlando, Fla.; Banbury, England; Budapest, Hungary; Dublin, Ireland; and New Zealand.

None of the Lanza children followed him into show business. But two of today’s best-known tenors, Luciano Pavarotti and Placido Domingo, claim Lanza as an inspiration. And two scholarship winners are now regular performers of opera, Petrella says.

“If there’s one wish I could have, it’s that I want him always to be heard and to be appreciated,” said Lanza’s daughter, Lisa Bergman of Los Angeles. “I just feel he should go on and on.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.