The Joint Is Jumpin’ at Boston’s Berklee

- Share via

The recent death of veteran cornetist Wild Bill Davison led to the by now familiar expressions of gloom heard at memorial tributes: The giants are passing on, the line grows thin, and who, if anyone, will be around to replace them?

These pessimistic reflections are not justified by the facts, according to Gary Burton, the award-winning vibraphonist who is in a unique position to foresee the future. Burton is an 18-year faculty member and currently dean of curriculum at Berklee College of Music in Boston. He was a student there in the early ‘60s before going on the road with George Shearing and Stan Getz.

“We have over 2,800 students at Berklee,” said Burton, “divided into those who are interested in pop music and those concerned with jazz. The jazz players subdivide into various contemporary and traditional styles. You might think that a young player would go for what is new and contemporary, but many of them are attracted to the jazz of the 1940s and ‘50s. This trend toward diversity is very healthy and augurs well for the future of the music.

“Movies like ‘Round Midnight’ and ‘Bird’ and Monk’s ‘Straight No Chaser,’ as well as people like Wynton and Branford Marsalis, have stimulated a revival of interest in straight-ahead jazz. Today, you find enough of an audience to support acoustic groups like Mike Brecker’s or my own band, as well as electric music played by Chick Corea or Pat Metheny.”

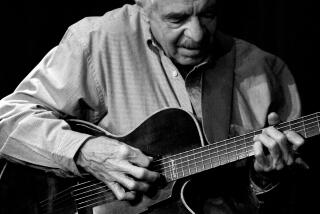

Burton’s remarks were made during the recent annual jazz festival cruise aboard the S.S. Norway. With a few exceptions, the major names among those who took part in this event were black and over 60, while the young musicians (including Burton’s group and an entire 19-piece ensemble from Dallas) were white. Several were second-generation jazzmen: Trombonist Al Grey had his son, Mike Grey, playing second trombone, along with bassist J. J. Wiggins, son of the Los Angeles pianist Gerald Wiggins, and Joe Cohn, a brilliant guitarist whose father was the saxophonist Al Cohn. Terry Gibbs, who played a vibraphone duet session with Burton, had his 25-year-old son Gerry on drums.

Burton’s own Berklee-trained sidemen seemed to bear out his optimistic beliefs. All in their 20s, they included Greg Gisbert, a trumpeter who at 22 looks about 15; Gildas Boclas, a bassist from France; Renato Chicco, a Yugoslav pianist still studying at Berklee and, most remarkably, Don McCaslin, a 23-year-old tenor saxophonist who amazed the audience one night by virtually stealing the show in a saxophone jam featuring such seasoned pros as Red Holloway, Phil Woods, David (Fathead) Newman and Flip Phillips.

Along with the educational advantages and incentives offered by Berklee and a growing number of institutions partly or exclusively devoted to jazz, a factor that has all but assured a thriving future is the internationalization of the music. Jazz courses are now held in many countries, a number of them in the Soviet Union. Still, Berklee remains the best known school and has produced a stream of promising alumni. A recent breakdown of the student body revealed that there are over 600 foreign students from nations around the world, including Aruba, Iceland, Ethiopia and Malaysia.

The foreign list is headed by Japan, with 138 students; Canada has 58, Israel 36, West Germany 24, Brazil 25, France 34.

Asked why students flock to Berklee from around the globe to study jazz, Burton said: “If you were into Japanese haiku, your dream would be to go to Japan and study with one of the masters. Jazz is one of the most popular music forms wherever you go.”

Burton remains firmly convinced of a healthy outlook. “I tell my students to keep an open mind, to move ahead with the music, the way the people we hold in most reverence did--the Miles Davises, the Duke Ellingtons.

“The men in my group have a broad range. They play demanding original pieces; they play standards and know the whole repertoire. My drummer plays a lot of rock gigs as well as jazz jobs. That kind of diversity will serve them well.

“No matter how the music evolves, whatever they feel is important for them to play, they’ll have the tools and the variety of experience to be a vital part of it as they move into the 21st Century.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.