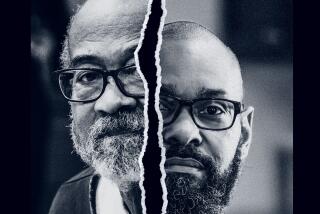

Did Power Quest Produce a Killer? : Slaying: Mike Blatt wanted to run the Seattle Seahawks, but now he stands trial for arranging the death of his former business partner.

- Share via

Larry Carnegie was running late. He was still at work at 6 p.m., and he had told the man he would meet him at the house on Tokay Colony Road at 6:30. Carnegie left Riverboat Realty, stopped to get $200 from a banking machine, then drove to the property he was showing in a rural area northeast of Stockton. He drove along California State Route 88, past rows of walnut and peach trees, through the town of Waterloo (pop. 298) and turned off on Tokay Colony Road. Carnegie drove two miles down the narrow country lane, which cut through tidy farms and open, furrowed fields. It was dark that night, Feb. 28, 1989, the sun had set at 5:59 and there were no street lights.

Carnegie pulled into the gravel driveway at 14152 Tokay Colony Road. Only the barest of light was shining from within the white wood-frame house.

They were waiting for him.

James Mackey and Carl Hancock had been at the vacant house for an hour. It was after 7 when Carnegie’s car came up the drive. Mackey was hiding in the garage. Hancock, who had told Carnegie his name was Sam Jackson, came out to greet the realtor. The two men went into the house and looked around for 15 minutes. The plan was for Hancock to lure Carnegie into the garage, where Mackey would kill him with a crossbow.

That was the plan, but it didn’t work out quite that way. In fact, very little of the elaborate plan to murder Larry Carnegie was carried out, other than the brutal fact of Carnegie’s death. Mackey and Hancock, who have confessed to the actual murder, did not turn out to be clever planners or even skillful killers.

The two former University of the Pacific football players made many mistakes, before and after Carnegie’s murder, that led authorities first to Mackey and, eventually, to Hancock.

And finally, to Mike Blatt.

Blatt is a 44-year-old Stockton developer well known in the San Joaquin Valley for his aggressive, and successful, negotiating. Blatt Development Co. did $120 million worth of construction in its first 10 years. Blatt owns apartment complexes in California, Arizona and Nevada.

Blatt is also a consummate negotiator in another sphere--professional sports. He became a successful sports agent in 1982 and at one time his Sunwest Sports agency represented more than 50 NFL players, making it one of the five largest in football.

Blatt hit the big time in another realm of sports, too, helping put together the sale of the Seattle Seahawks in August of 1988. Blatt brought together the Nordstrom family and the eventual buyer, Californian Ken Behring. Blatt had a stake in the deal as well, putting up $8 million in escrow for a future 10% interest in the team.

And, for a few weeks in February of this year, Blatt was in his glory, acting as the Seahawks’ interim general manager. He boldly proclaimed that he would “create a dynasty” in Seattle.

Blatt didn’t have an opportunity to do that. On Feb. 22, after what some would call a power struggle, Blatt was out as general manager and former Raider coach Tom Flores was in.

Six days later, Larry Carnegie’s body was thrown down a ravine in remote Sonoma County.

James Mackey later testified in a pretrial hearing that he killed Carnegie as “a favor” to Blatt. Mackey, who had been a client of Blatt, testified he had become a real estate agent in order to get closer to the developer, whom he admired.

Asked why he was willing to kill for Blatt, Mackey testified: “I wanted to have a close relationship with Mike, eventually a working relationship. I wanted to establish some trust between us.”

On Dec. 8 in Stockton, Mike Blatt was ordered to stand trial in the murder-for-hire of Laurence J. Carnegie. Municipal Judge Thomas B. Teaford ordered, after a three-week preliminary hearing, that Blatt be bound over for trial in Superior Court and be held without bail on a first-degree murder charge. Teaford also found that “special circumstances” existed, meaning that Blatt could face the death penalty if convicted.

The descriptions of the murder were obtained from the testimony of Mackey and Hancock during the pretrial hearing and from court documents.

To fully understand why Mike Blatt has been charged by the State of California with hiring Mackey and Hancock to kill Carnegie, it is necessary to understand how the pursuit of power brought Blatt and Carnegie together, enabled them to profit together, and, ultimately, split them bitterly.

To Eual D. Blansett, the deputy district attorney who is prosecuting the case, Blatt and Carnegie were strong-willed men who had faced off like “praying mantises in mortal combat. They would both starve to death before they would unlock in combat.”

Carnegie began to work for Blatt Development as a broker and property manager early in 1982. Carnegie and his wife Karen operated Riverboat Realty, but he wanted more. Carnegie thought that to be associated with Blatt’s already successful business would further his career and increase his expertise in commercial real estate. The charismatic Blatt and his flourishing commercial development empire represented that opportunity.

Carnegie, 38, was by most accounts a hard-driven man, but was also a doting father to his three young daughters. More than one observer in the case has pointed out that Carnegie and Blatt appeared to have similar personalities.

Said Karen Carnegie of her husband: “Larry was really confident, and he wasn’t afraid of anything. If he felt he was right, he wouldn’t back down.”

Carnegie had worked with Blatt for five years when another in a series of soured business deals prompted Carnegie to quit. The deals gone bad also give the prosecution one of its theories as to why Blatt would want Carnegie dead.

Before he was killed, Carnegie had filed two lawsuits against Blatt.

In one of them, filed the day after he had left Blatt Development in February of 1987, Carnegie demanded $200,000 in commissions and other considerations that he claimed Blatt had withheld. Carnegie also claimed that Blatt had failed to pay legal fees incurred on a previous business deal.

Blatt countersued.

Lawsuits were nothing new to Blatt the developer. One of his largest and most controversial projects was the Stockton Ramada Inn, built in 1982. Homeowners in the area charged that they had been promised that a shopping center would be built on the site and were angry about the late-night disruptions a hotel might cause.

Neither was Ramada, Inc., happy with Blatt and his partners. The company sued Blatt in 1987 for underpayment of franchise fees and later terminated its franchise agreement with him. Last May 24, a U.S. District judge in Sacramento awarded Ramada a judgment of $263,406 in the case.

Blatt is appealing that decision.

Another motel deal, this time involving Carnegie, also cost Blatt. In May of 1985, Carnegie was Blatt’s broker in the sale of the Fremont Inn, which sold for $1.8 million. Two months later, the buyers sued Blatt and Carnegie for fraud and misrepresentation, claiming they had provided inflated income figures. Blatt settled out of court for $250,000.

Then Blatt sued Carnegie for $600,000, claiming it had been Carnegie who had misrepresented the hotel’s income. That suit is pending against Carnegie’s estate.

The two hotels and a condominium complex became the subject of further lawsuits between the two men.

Dist. Atty. Blansett maintains that the lawsuits and Blatt’s growing personal dislike of Carnegie provide another motive for Carnegie’s murder.

“These lawsuits were of a different sort than we normally see,” Blansett said in his closing remarks last week. “These lawsuits arose out of a personal relationship between Mr. Blatt and Mr. Carnegie. They had a major disagreement of a financial nature.”

It may be difficult to imagine Blatt, who has a personal worth of about $50 million, getting that worked up over yet another lawsuit, but evidence was presented in the pretrial hearing that Blatt was indeed worked up. Mackey testified that Blatt casually told him that he wouldn’t mind at all if Carnegie weren’t around anymore.

“I asked (Blatt) if he wanted me to find somebody to take care of it,” Mackey testified. “He asked if I could. I said, ‘I’ll see.’ He said, ‘My name can’t be mentioned.’ ”

Asked what he thought Blatt had meant by “take care of somebody,” in another conversation, Mackey replied, “Have them killed.”

Mackey was crouched in the garage, waiting there in the dark . He knew something had gone wrong. Hancock and Carnegie were supposed to come inside the garage but there they were , standing outside by the cars . Mackey peered through the half - open door and heard them talking. Mackey saw only Carnegie’s silhouette in the doorway. He raised the recently purchased hunting crossbow, closed his eyes and pulled the trigger. The 16-inch steel bolt hit Carnegie in the back, went through his chest and landed on the front lawn. He yelled, “I’ve been shot,” stumbled from behind the car, then crumpled to the ground.

Mackey ran out of the garage and Hancock, who was kneeling next to Carnegie, said, “He’s still alive. We have to suffocate him.” Mackey looked down at Carnegie, who was writhing on the ground. Carnegie appeared to recognize Mackey and uttered what would be his last words, swearing at his murderer. Mackey and Hancock were in a panic. Nothing was going according to plan. Hancock ran to the rental car and got a blue sleeping bag from the trunk. They held Carnegie down and attempted to smother him. At that moment, Denise Brock and Debra Ybarra pulled into the driveway at 14152 Tokay Colony Road. Brock was going to drop off house keys for workmen who would replace carpets the next day. Her car’s headlights swept the scene. Hancock ran toward her car. Brock threw the car into reverse, drove down the road and called the San Joaquin Sheriff’s office from a neighbor’s phone. Back at the vacant house, Mackey and Hancock put Carnegie’s body in the trunk and drove off, discussing a new plan as they sped away.

Blatt threw himself into the Seahawk job, although his title and the nature of his responsibilities were never spelled out. There was much speculation regarding Blatt in the Seattle papers.

Blatt was seen in Seattle as being a little too much. He was charming but also chilling. And he got off on the wrong foot with Seahawk fans with his first executive decision--to increase ticket prices.

While he leased a home and tried to gain acceptance in the Seattle community, Blatt’s presence was having an effect in the clubby circle of NFL owners. A player’s agent, he was viewed as a “them,” not an “us,” by others in management.

Blatt argued that he could easily make the transition from one side of the bargaining table to the other, and that his experience as an agent would be valuable as a general manager.

In part to appease his critics, Blatt sold his interest in Sunwest Sports to his partner, Frank Bauer.

That failed to soothe some owners, who had expressed their concerns about Blatt’s “unpleasant negotiating tactics” during his career as an agent. Some owners’ objections grew even more strident when it became known that Blatt was buying into the team.

Behring heard the talk. So did minority owner Kenneth Hofmann.

Hofmann later testified that his growing concern about Blatt’s background led him to hire a private investigator to check out Blatt.

“The total report on Mike Blatt was all business-related civil suits, nothing criminal,” Hofmann said. “But you see he had a lot of business problems, you see he had a lot of problems in a short period of time. You don’t want to do business with him.”

Hofmann, who owns 25% of the Seahawks, said the investigation revealed that Blatt was involved with “more than 400” lawsuits in San Joaquin County (the prosecutor said later that the report turned up 31 lawsuits in the county since 1978.)

Hofmann said that litigation aside, he was put off by Blatt’s personal style, which he found too flamboyant. He told of attending an NFL owners meeting where, “Mike was getting all the press,” Hofmann said. “He was walking around like he owned the Seattle Seahawks. That bothered me.”

Nevertheless, the public perception was that Blatt lacked only the official anointing. The competition between Blatt and Flores for the dual job of general manager-president was frequently described as a power struggle, yet it hardly seemed to be that.

When Behring had fired Mike McCormack, the previous general manager, Behring had said he wanted to replace him with a business man, not a football man. Blatt, the businessman, seemed a logical choice over Flores, a football man.

So Blatt was clearly bitterly disappointed that he eventually lost out to Flores. Still, he found a way to save face. On the day of the announcement, Blatt told reporters that Behring had offered him the job, but that he had turned it down because he didn’t want to relocate to Seattle. Blatt, who is divorced, has a teen-age son and daughter.

“My children are too important to me,” he said.

Hancock was driving , swerving all over the road. Mackey thought he was out of control and told him to pull over. Mackey got behind the wheel and headed out on California 12. He had a vague idea about driving to some place in Sonoma County. The original plan to tie 25-pound dumbbells to Carnegie’s legs and dump him in Lake Tahoe had gone sour the day before, when they had been unable to rent a boat to get to the middle of the lake. Now as they were driving, they heard noises from the trunk. Could be the weights rolling around. Could be their nerves. They had already been driving for about an hour so they stopped the car on a quiet road near Cloverdale. Hancock went back to the trunk and opened it. He called for Mackey to come on back. Carnegie wasn’t dead. Hancock took some rope from the trunk and wrapped it around Carnegie’s neck. He held one end and gave the other to Mackey. Each man pulled as hard as he could until Carnegie was dead. Hancock closed the trunk. They quickly got back in the car. Got to get rid of the body. Mackey drove a way down the road. It was dark but they could see a deep gully along one side. They got the body from the trunk and put it on the ground. Hancock nudged it over the edge of the gully , into a garbage dump. They got back into the car and drove to a hotel in Richmond , where they showered and changed clothes. They tossed the weights in a dumpster outside. Back in the car, they headed for Vallejo. While Mackey was driving across a bridge, Hancock threw the crossbow and the rope out the window. Mackey knew the area. He found a carwash and then cleaned out the trunk. Hancock bought two baseball caps. They drove back through Sacramento and visited a friend of Mackey’s. They got back to Stockton about 6 a.m. on March 1. Mackey dropped Hancock off at his apartment. They agreed not to see each other for a while.

As a sports agent, Mike Blatt had been both skillful and successful. His negotiating style was marked by its boldness and, often, intransigence. He was not shy about advising his clients to hold out. A holdout in the NFL, where the average length of service is four years, is a potentially career-ending strategy.

One of Blatt’s first clients, Pittsburgh Steeler linebacker Mike Merriweather, sat out all of last season while waiting for his contract to be renegotiated. Another, Keith Millard of the Minnesota Vikings, left the Vikings and played in the old United States Football League during a contract hassle.

The Rams’ Henry Ellard held out for about half of the 1986 season during negotiations that were so acrimonious that one sportswriter wrote about Blatt being Ram management’s public enemy No. 1.

The Rams, who have something of a reputation as hard-liners, found that going toe to toe with the unmoving Blatt was getting them nowhere. In Ellard’s case, and in the case of a handful of other Sunwest clients, the Rams found it easier to deal with Blatt’s partner, Bauer.

As with most of Blatt’s former clients, Ellard says he is shocked by Blatt’s arrest and believes his former agent has been framed.

In 1987, quarterback Kelly Stouffer, another of Blatt’s clients, made NFL history. When Blatt could not come to terms with the then-St. Louis Cardinals, he advised his client to sit out the season. Stouffer became the first first-round draft pick ever to do so.

Blatt also counseled Stouffer to sue the league to gain release from the Cardinals. And last spring, Blatt negotiated Stouffer’s trade to the Seahawks, who gave up a first-round draft pick got a promise that Stouffer would drop his lawsuit.

At least one former client was upset enough with Blatt to sue him. That man, John Farley, has a chilling tale to tell of the consequences of that lawsuit.

Farley, who played at Cal State Sacramento, was drafted by the Cincinnati Bengals in 1984. Earlier that year he had signed with Sunwest Sports. He asked Blatt to manage not just his career but also his investments.

Farley, a running back, played with the Bengals, the Green Bay Packers and in the Canadian Football League before his career was ended by injuries in 1987.

Farley said he began to notice a pattern of “unsuitable investments” and sued Blatt in 1987. In October of 1988, Farley was awarded $204,886 in an arbitration judgment. The case is still on appeal.

During the preliminary hearing in the Carnegie case, there was testimony that Farley had been the original target. Mackey testified that Blatt had asked him to “take care of” John Farley and that Mackey arranged for Farley to be followed. Then, in early February, the target changed.

“I don’t recall his exact words,” Mackey testified regarding his conversation with Blatt. “He said something like, ‘You need to do the other one first.’ I didn’t ask why. I remember something about the (Carnegie) lawsuit and the date coming up.”

The events of Larry Carnegie’s death are being recounted in the somber chambers of Department B, Stockton Municipal Court.

The courtroom has been packed and the judge has ordered stringent security. Every person entering the court must pass through a metal detector. Reporters must sign in every day and provide a driver’s license. Four armed sheriff’s deputies are in the courtroom at all times.

And the case has been nothing if not bizarre.

If Denise Brock had not pulled into the driveway that night, the police would not have been alerted as quickly as they were. She also identified the rental car.

If Mackey had not rented the car in his own name and not used his own credit card, it would have been more difficult to trace. If he had not flirted with the saleswoman at the rental agency--even leaving her his business card--perhaps she wouldn’t have remembered him.

If Mackey and Hancock had not panicked and left the crossbow bolt and the sleeping bag in the yard, investigators might not have traced the items to the sporting goods store where they were purchased.

If they had left the body somewhere other than a much-used garbage dump, perhaps it wouldn’t have been discovered so soon.

Mackey testified that he had received a total of $5,500 from Blatt to purchase equipment and fund a getaway trip to Los Angeles and Mexico. Hancock said he got $600.

In his closing argument last week, Michael Thorman of Hayward, Blatt’s defense attorney, hammered on the circumstantial nature of the case. Where was the physical evidence that linked Blatt to the murder? There was only the testimony of two confessed killers.

In return for escaping the death penalty, Mackey and Hancock agreed to testify against Blatt. Mackey, 25, has pleaded no contest and Hancock, 26, has pleaded guilty to first-degree murder. They are awaiting sentencing and could be eligible for parole in 16 years and eight months.

Blatt did not take the stand, but is expected to in the trial. Blatt is to appear in court Friday, possibly to set a trial date, but that may be delayed as the case will most likely be tried out of the Stockton area.

“In order for Mr. Mackey to make some sense, you’ve got to believe that Mr. Blatt is going to . . . trust his life and his fortune to this bumbling assassin who can’t keep his marriage together and is having . . . financial difficulties,” Thorman said.

Thorman also says that for every theory the prosecution will put forth, he will have another to show why Mackey had his own motive for killing Carnegie.

But Thorman has a lot of work to do. He will have to explain the vast array of circumstantial evidence lined up against Blatt. He will have to explain two checks Blatt gave to Mackey, one the day before the murder and another the day after.

He will have to explain numerous phone calls to and from Mackey, all around the time of the murder. He will have to temper Blatt’s reputation as a renegade and tone down Blatt’s often arrogant courtroom demeanor.

And, Thorman will have to explain a damaging piece of evidence detectives found in a drawer of Blatt’s office desk.

There, fastened with a paper clip, they found a news article about Carnegie’s death and this note, on Blatt’s stationary: “Larry We Are Even!!”

Times researcher Peter Johnson contributed to this story.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.