Reporting the Story of the Decade

- Share via

Get ready for a decade of premature millennialism.

Especially in magazines, this trend--maybe it’s a syndrome--is off to a flaming start. The next millennium doesn’t even begin for more than a decade--which is soon enough, maybe too soon. But judging from some of the January issues now flowing to newsstands, the 1990s won’t even exist, except as a sort of calendrical hiccup before the next epoch.

Mirabella is the most blatant example. In its “Guide to the Millennium” in the kickoff pages, the fashion / style monthly has the grace to acknowledge that 1990 is “the beginning of the big ending” and that “the hype’s already begun, and you can settle in for another 10 years of it.”

After this genuflection to candor in the media, however, the magazine then shamelessly wallows in its own version of thousand-year hype with “The Best and Worst of the Millennium,” a short list of the monthly’s favorite and unfavorite things over the centuries.

Among the best: Ralph Nader and St. Francis as the best fanatics; the Gutenberg Bible, “War and Peace” and the telephone book as the best books; sunglasses as the best accessory, and the 18th as the best century.

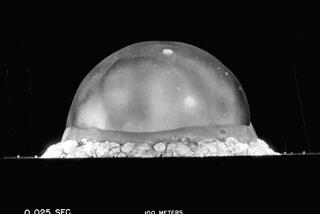

Among the worst: the atom bomb and the alarm clock as inventions; Deborah Norville as the worst TV anchor; dwarf tossing as the worst sport, and Leona Helmsley as the worst mogul.

Up to a point, this is fun, even witty. It also seems to hint that attention spans may be expanding to a historical perspective. On the other hand, it may just as well indicate that 1,000 years of history can be trivialized into a list no longer than a chart of the top-selling videos. And that could mean the next 10 centuries won’t even rate a retrospective.

Fortunately, Mirabella also offers an essay, “Name That Decade,” by Yale professor Harold Bloom. And Bloom uses it partly as a vehicle to twit the predictable reactions to the rounding out of the 20th Century. “All of us ought to fortify ourselves against the tides of cheap apocalypticism that will greet Jan. 1, 1990. Those tides convey the impression that Jan. 1, 2000, is likely to be a grand Rapture, in which all of us are taken skywards, up into the end of time.”

Bloom also analyzes the compulsion to tag decades. “Decade-itis . . . is a benign enough social disease and should be regarded as a form of information anxiety . . . Nietzsche once observed that we find words for what we no longer hold in our hearts, so that there is always a kind of contempt in the act of speaking. We try to control through naming, but perhaps we merely package ourselves when we endeavor to name decades. Keeping up with a wave that is always breaking is clearly an anxious activity, and beneath the fun of decade-naming one hears a kind of dread.”

Meanwhile, Newsweek has put out a special edition called “The 21st Century Family: Who We Will Be, How We Will Live.” There’s more certainty about the next century in the cover headlines than most people probably feel about getting through the day, let alone a week.

Thankfully, Newsweek proves as perplexed as everybody else, once the reader gets beyond the cover. It uses the kind of flabby, amorphous nonstatements that news weeklies have perfected when their crystal balls go opaque.

“We must create accommodations (to the family) that are new, but reflect our heritage,” Newsweek intones in an overview piece. “Our families will continue to be different in the 21st Century except in one way. They will give us sustenance and love as they always have.”

Finally, U.S. News & World Report kicks in with a special double issue, “Outlook 1990s,” which turns out to be just as uncertain about--and impatient with--the new decade as Mirabella.

The issue leads with the kind of safe forecast that instills queasiness: “What confronts us in the decade ahead is promise. (No more or less than that can be predicted with assurance.)” The introduction ends with this statement: “This is 1990 we’re looking in the eye, six years past Orwell’s nightmare, the run-up to the new millennium. Let’s get on with it.” The year 3000 can’t get here fast enough.

Geographic Returns to Alaska Spill Site

All the hoopla last week over National Geographic’s presentation of new evidence that Cmdr. Robert E. Peary probably did reach the North Pole obscures the January issue’s overall content. The entire magazine is more than the usually engaging package, beginning with a look at the cleanup efforts after the Alaska oil spill, a disaster that lingers longer than a tanker captain’s hangover.

Revisiting Prince William Sound months after the spill, Geographic writer Bryan Hodgson found surprising areas of rejuvenation, such as salmon swimming in a previously oil-slicked stream. Yet the gargantuan and mind-boggling cleanup effort that included wiping oil off rocks with paper towels may have become a disaster in itself, a federal scientist told Hodgson.

“Sometime in July, the cleanup crossed the line from being beneficial to being harmful. In effect, we created a second oil spill,” Dr. Jacqueline Michel of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration said.

Also in the issue, a lengthy look inside the Kremlin helps put a human face on the remaking of the Soviet state. Photographs, including some taken in the Council of Ministers building, where day-to-day decisions are made, do much to expose the normally off-limits sanctums. A photo of Supreme Soviet members voting against legislation proposed by the Communist Party may be worth more than the typical thousand words.

Editor Wilbur E. Garrett said the January issue represents the largest circulation in the history of the magazine, pushing close to 11 million. But a recent membership price increase (Geographic readers are members, not subscribers) to $21 annually probably means circulation will drop somewhat in the months ahead, he said.

Unlike other magazines, Garrett said, National Geographic isn’t jumping through hoops to get ready for the 1990s--or the next millennium. “It’s just one more year,” he said, adding that he expects the magazine to “evolve intelligently.”

Nonetheless, the people on the marketing side of the National Geographic Society are doing their bit to reposition the magazine for the years ahead. Lately, they’ve been running ads in Advertising Age and other trade publications, touting the magazine’s marketing clout--a total of 37 million readers spending an average of 75 minutes with each issue.

National advertising director Joan McCraw said the ads have received both positive and horrified responses. Some folks were shocked by the advertisement headlined: “Stop 37 million readers in their tracks every month.” The reason? The headline ran with a powerful photograph of a lion making a kill, its teeth and claws sinking into a stunned and terrified wildebeest.

“Some people said it was too brutal, and others wanted to know, ‘Can we get a blow-up of this? We think it’s fabulous,’ ” McCraw said.

However, response was almost entirely positive, she said, to a layout showing the interior of a cathedral and the legend: “The only book more respected than ours doesn’t accept advertising.”

McCraw claims the campaign has already begun to pay off. For January and February, advertising is up 28.1%, she said, adding that she hopes to capitalize on the magazine’s reputation for environmental and science reporting, both of which are now “in vogue.” While memberships and other non-advertising sources account for most of the society’s income, McCraw said, she hopes that advertising can be increased from about 15% of revenues, or $50 million, to about 25% within the next five years.

Although she’s pleased that public concern about the environment is a plus for the Geographic, McCraw echoed Garrett when she said that the magazine doesn’t remake itself just for the heck of it. “We’re not trendy, and we never will be trendy,” she said.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.