The Only Law Around : Armed With Semiautomatics and Calm Manner, Community Deputies Patrol County’s Last Frontier

- Share via

They patrol the deserts and mountains of Los Angeles County’s last frontier in Chevy Blazers, carrying semiautomatic rifles along with the Sheriff Department’s standard-issue shotguns and pistols.

They take on wandering bears, paramilitary groups, escaped horses, desert nomads, poachers and drug-dealing urban gang members who have set up shop in the Antelope Valley desert.

And they like it.

“I hate the big city,” said Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Deputy Fred Fate, 53. The quintessentially gruff and burly 29-year veteran will retire in March after five years on solo patrol in Acton, a mountain community south of the Antelope Valley. “I prefer the country. I prefer being outside with people.”

“I’m like my own station,” said Deputy Richard Ingalls, who is the deputy in the unincorporated desert areas of Lake Los Angeles, Littlerock, Sun Village and Pearblossom. “I’m my own detective. I do my own follow-up work.”

Unlike police officers who commute to their beats from distant suburban refuges, Fate and Ingalls work out of their homes in the far rural reaches of the Antelope Valley Station’s 1,500-square-mile patrol area. Like frontier sheriffs of old, the community deputies are well-known and often the only law around.

“Let’s face it: They’re out there by themselves,” said Sgt. Ron Shreves, spokesman for the Antelope Valley station. “There are situations where bravado alone is not going to prevail. Maturity is a big factor. You need someone experienced, someone able to talk to people.”

The Antelope Valley community deputy program was created five years ago to respond to complaints in Acton and Agua Dulce about slow response times and minimal contact with the Sheriff’s Department. Increasing population and crime subsequently led to creation of a community deputy in the eastern valley and one in the western mountain communities of Leona Valley. The only similar patrols in the county are resident deputies in Gorman and on Catalina Island.

“It’s a necessity out here,” said Greg Gerard, principal of Challenger Middle School in Lake Los Angeles, where 15,000 residents live amid desert buttes. “It’s the only link we have. Prior to that, we would call the department and get a car in a half an hour or maybe four or five hours.”

Jim Gary, former president of the Agua Dulce Civic Assn., said residents think highly of Fate, who serves on the school board and is active in several Acton community groups. Fate’s ties to the area have improved police protection and community relations during the day, when he is on patrol, Gary said.

But at night, Agua Dulce residents believe they do not get enough service when other, rotating deputies are less familiar with the winding roads and stark canyons south of Acton, Gary said.

“Ninety percent of the people still want quicker response times,” he said. “Under the best conditions, it takes 20 minutes.”

Some residents have said the Sheriff’s Department should consider shifting Agua Dulce into the Santa Clarita station’s jurisdiction. Sheriff officials at the Lancaster station said they are working to improve coverage and expect improvement when a satellite station in Palmdale opens in the spring, because deputies will be based closer to Acton and Agua Dulce and will be able to spend more time there.

But deputies also said the potential for slower response times come with the territory.

“That’s the reality of living in the country,” Fate said.

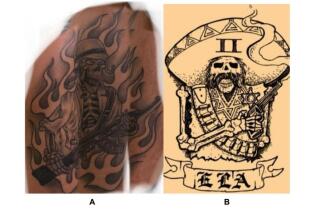

A less predictable country reality that deputies have confronted is gangs, particularly in Lake Los Angeles and Sun Village. Local youths, some of whose parents moved from the city to escape urban threats, are claiming allegiance to Los Angeles-area gangs and causing problems in schools and neighborhoods.

“It’s a very big shock to the parents,” Ingalls said. “They say ‘We moved here to get away from that.’ And you tell them: ‘It’s everywhere. You have to make a stand.’ ”

Ingalls, 32, oversees a vast and diverse territory, about 400 square miles. Two other deputies help police the area bounded by the Kern County line on the north, the city limits of Lancaster and Palmdale on the west, the San Bernardino Mountains on the south and the San Bernardino County line on the east.

On a crisp, sunny morning recently, Ingalls cruised from the peach fields of Pearblossom into Littlerock and Sun Village. Ranch-style houses with horse corrals alternated with tumbledown shacks and squalid trailer parks. Ingalls pointed out several of the local “rock houses” and surveyed a known drug location where two vacant-eyed women slumped on the front steps. He has put six houses out of the rock cocaine business in the past year.

In addition to the cocaine trade--run primarily by gang members who sell in the Sun Village area and in Palmdale and Lancaster--Ingalls’ turf has been home to heavily armed, well-disciplined members of outlaw motorcycle gangs who use remote spots for the production and sale of methamphetamine.

And even among non-criminal residents, including many deputies and officers from other departments who live in the Antelope Valley, guns and ferocious dogs are common household items.

“Everybody has a gun,” said Ingalls, a 10-year veteran. “It makes you pick and choose your moments about what to do and when to do it. You don’t have the luxury of having other units two minutes away like you do in the city.”

A radio call summoned Ingalls to a desert crossroads, where he and another deputy conferred with bail bondsman Bill Herman of Lancaster. Herman was searching for “Marino the German,” described as a tattooed motorcycle enthusiast who had missed a court appearance on a charge of dealing methamphetamine. Deputies assist bondsmen in apprehending bond jumpers if there is a warrant and they are considered dangerous.

“I’ve only got a couple of days to catch his scallywag butt,” Herman growled. He said he had received a tip that his quarry was staying with an acquaintance known as “Junkyard Jim.”

Ingalls and the other deputy followed Herman’s pickup truck down a dirt road to barren flatland near 145th Street East and Avenue S. They sped into a makeshift, debris-choked compound that looked like something out of “The Road Warrior”: a trailer, several old school buses converted into living quarters and a shed surrounded by scrap metal, machine parts, an old water tower lying on its side, lumber and fishing rods. There were more than a dozen dogs, some in pens, others nosing through junk.

But Marino was nowhere to be found. A woman in a dingy red jumpsuit and several teen-age girls emerged from a trailer and stared at the outsiders. Ingalls and the others conferred with “Junkyard Jim,” a slight man in sunglasses, who said he sent “The German” packing several months ago because the man’s pit bull was attacking dogs and people.

“You get a lot of people living out in the desert like that,” Ingalls said afterward. “They have to truck in water. You find all kinds of stuff at some of these places, sometimes stolen vehicles, property, guns.”

More exotic stolen property has turned up in the hands of poachers he has arrested, Ingalls said, such as sea turtle shells, pickled monkey hands, jaguar pelts and hawk chicks stolen from their nests for sale to falconers. Ingalls has also had to shoo a full-grown bear back into the hills after it entered a back yard to eat pears. And he has cited an elderly desert denizen for using a large mirror in an attempt to blind pilots landing and taking off at a nearby airfield.

Fate’s adventures include the pursuit of an escaped white reindeer that managed to find refuge after he shot it with a tranquilizer dart. The reindeer came to before it could be located, and Fate finally called in a neighbor who is adept with a lasso.

Neither Fate nor Ingalls has had to fire the AR-15 semiautomatic rifles, which they, unlike most patrol officers, are authorized to carry. But Fate said he has displayed it in confrontations with heavily armed military groups who do illegal shooting in canyon and forest areas.

“A good part of the job is bluff,” Fate said. “You learn how to bluff a guy into being peaceful.”

The community deputies must be especially skilled because they work alone. Units from the main station and from Los Angeles, such as homicide detectives who may be completely unfamiliar with the Antelope Valley, depend on their expertise, said Lt. Tom Pigott, who heads operations in the Antelope Valley station.

“He is like the lead scout,” Pigott said, recalling an incident in which Fate guided a SWAT team’s pursuit and arrest of a well-armed band of burglars specializing in mountain homes. “His knowledge is invaluable to us.”

But the frontier is succumbing to the rapid urbanization of the Antelope Valley. And the pressures of growth appear destined to change, if not diminish, the role of the solitary deputy on the range.

“It will take on less and less significance as the community continues to grow” and more patrol units are added, Pigott said.

Deputies and residents still feel there will be a place for deputies who are a fixture in the rural areas where they live and work.

“There are places where you can’t do it,” said Gary of the Agua Dulce Civic Assn. “But the man who carries the badge should be part of the community wherever it’s possible.”

Fate, who plans to remain active in Acton for several years after his retirement before moving to his native Oregon, said the size and ruggedness of the beat require a deputy who knows his way around.

“You get out in the country,” Fate said, “and it’s a whole new ballgame.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.