Horror’s New King : With Films and Fiction to His Credit, Clive Barker Is a Screaming Success

- Share via

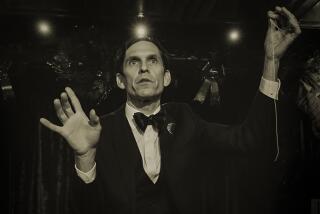

English horror-tale author Clive Barker clutches a coffee table in a white-knuckle grip, as if to keep it from attacking.

“Is that table alive?” a guest asks politely.

“Probably not,” he answers, as if unsure. But he is sure that it could be, that things are never what they seem, that “everything--even a table--has imagination.”

Barker’s own imagination is bloodcurdling. The baby-faced 37-year-old gore-monger became an instant cult figure in England seven years ago with publication of “The Books of Blood.” The six volumes of short stories feature vile creatures who commit erotic, demonic and otherwise unthinkable acts--and sometimes make their victims like it.

Now, 10 books and two film-directing stints later, Barker is one of the richest, most talked-about horror authors in the world, acclaimed by critics (and by Stephen King himself) as “the new Stephen King.”

With money piling up from books printed in “about 17 languages,” a new book out in February (“The Great & Secret Show,” Harper & Row), plus a $10-million contract from the publisher for his next four volumes, Barker still looks and talks like the struggling University of Liverpool philosophy student he was until seven years ago.

“I was on welfare until I was 30,” he said last week at his rented home in the Hollywood Hills. Barker was in Los Angeles to direct “Nightbreed,” a movie based on his book “Cabal.” He also wrote and directed the 1987 film, “Hellraiser,” based on his novella, “Hellbound Heart.”

“I don’t drive because I was always so poor I never thought I’d have enough money for a car. So I never bothered to learn.”

Now that he has the money, Barker says he’s not all that interested in material things.

“I don’t go in for cars or clothes,” he says, pointing to his blue jeans and black turtleneck.

What Barker does go in for is writing that opens up those “secret areas” of imagination that most of us are too fainthearted to acknowledge we possess.

“We spend eight hours of every 24 asleep, visited by images that are irrational, elaborate, and that influence our waking lives in ways we can only guess at.”

But, he says, almost all of that gets repressed.

“We awake from an erotic dream which contains a frisson we didn’t even think we were capable of. We immediately shut it out, put it behind us. We don’t think about what it means, what our mind is telling us about our secret passions and desires.

“We also deny our interest in the forbidden aspects of death,” he continues, “and in the fact that our bodies are an hour older and closer to capitulation than they were 20 minutes ago, when we started this discussion.

“We even deny our hope for God and our fear for hell. We live rational and for the most part secular lives, preoccupied with the minutiae of mortgages and kids.

“Yet--and I believe this is universal--something in us all needs talk of demons and angels.”

And monsters.

People love monsters because they need them, he says. Monsters are good for us. They force us to look at those things that we hide from ourselves.

In fact, we like horror fiction “because we want to meet the monster. We want to shake its hand, probably to dine with it.

“We go to ‘Dracula’ not to see Van Helsing wave his crucifix, but for the company of a monster who presents his sexual appetites--all his appetites--without apology.

“We go to ‘King Kong’ for the company of a 60-foot ape--a pagan image of unleashed animal energy” whose passions are actually quite “wholesome” and not so different from our own.

But most horror fiction, he says, is “morally placed,” so that monsters must be “shunned, cast out, not clearly seen.”

But Barker says he “seeks out the beast.” His monsters are “hugely delineated, their psyches investigated.” He believes his readers can meet these monsters head-on, without flinching, and thereby face their own demons. Barker grew up in Liverpool, thinking himself an ordinary child. But he recently heard his parents (his mother was a school officer; his father, a personnel director) interviewed and learned for the first time that they were worried from the start “they might have a crazy on their hands. I apparently used to draw weird pictures and talk to people who weren’t there.” (Barker’s more recent weird drawings will soon be published in book form.)

His current concern, “The Great & Secret Show,” is not strictly a horror novel at all, but rather a “fantasy full of awe and wonderment, with some very dark passages.”

The book features a demented postal worker, four virgins impregnated by monsters representing good and evil, tentacled creatures who sap the human spirit and a Simi Valley town that swallows itself whole.

“To call it horror is to miss the point. Images of great good sit side by side with the horror.”

And though he’s pleased to be likened to Stephen King, Barker says his work is very different.

“King loves the poetry of the ordinary. I love the poetry of the extraordinary.”

King’s characters, he says, love their everyday lives. Things that occur to disturb those lives--”like a rabid dog or a possessed car”--are intrusions and become the enemy.

In Barker’s new book, the status quo is the enemy.

Characters with closed minds, who ignore their imaginations in order to lead safe lives, are bound to suffer.

Those who face the demons Barker conjures for them--who fight with and learn from them--are likely to cross through horror into a kind of paradise.

“The Great & Secret Show” has a complicated, mystical plot that weaves in and out of time, above and below earth, through uncharted regions of the characters’ minds. At the end, when reality cracks, and the ground opens up to swallow a whole town, survivors are those who “love each other and themselves, who have spiritual strength and imaginations not wizened” by too much emphasis on material goods, Barker says.

Since his career has taken off, the author’s main indulgence has been the purchase of a Georgian house in London where he keeps his collection of dead “scorpions, locusts and other odd things.”

“People ask me, ‘How can you love a scorpion?’ Well, a scorpion is a fabulous, wonderful, totally alien thing,” Barker crows. “What’s important is to celebrate the whole world, the whole thing. We live in this wonderful, imaginative environment, often sealing ourselves off from it in little cells of homogenized life. I like people to look at the real world and see how strange it really is.

“A pet dog for example, is very strange,” he says. “He’s another entire species who has chosen to be with you, chosen this very primal liaison that goes back to the cave man.

“I tell people, ‘You have a tame descendant of a wolf living in your house, with its own thoughts and its own views and yet there’s this wonderful unification with that strange thing.’ ”

Do most people think Barker’s enthusiasm and complexity--not to mention his taste in pets--a bit odd?

Not at all, he says. Especially when his ideas are on paper or film. His kind of fiction touches a universal chord, he says. It springs from ancient narrative forms--myth, folklore and fairy tale. And part of his passion for working in this genre is the “wonderful tension that comes from writing something which has the energy of a populist narrative--scares, funny stuff, erotic passages. (It has) the whole Shakespearean mix, in other words, but also has the ‘to be or not to be’ speech.”

“Hamlet is a revenge tragedy,” Barker says, but we “allow Shakespeare the philosophical ruminations because we know very well there’s murder in the air, ghosts walking, and mad girls about to commit suicide. That’s neat.

“I’ve always believed that if you tell a story well, you can drop into the fast-flowing stream of your narrative fairly heavy boulders, and they’ll get carried along.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.