Employers Pressing Hospitals for Cost Data

- Share via

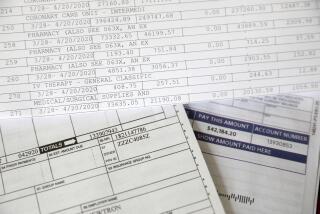

A few weeks ago, a Pennsylvania state agency released a report showing wide disparities among Pittsburgh-area hospitals in the cost and results of treating patients with the same kinds of illness.

Hospitals are accustomed to providing cost figures and death rates to federal and state agencies, but this report was starkly different. It listed the hospitals by name, showing each facility’s average cost for a particular procedure, rate of complications, length of stay and other information not previously made public.

Many of the hospitals cried foul, complaining that the data collection method was flawed and that it covered too short a period to be meaningful. Nevertheless, experts say that as health-care costs continue to escalate the demand for more such detailed information will only increase.

The Pennsylvania report, required by a new state law, was the first of its kind, but three other states have mandated similar reporting requirements, and California may soon join them.

Employers in the forefront of health-care cost containment argue that they can’t control costs unless they can find out which health-care providers are cost-effective. They want to know more than just price differences. They say they want to know which hospitals will get patients well with the fewest complications and will do the job right the first time so that patients won’t have to keep returning to the hospital.

The employers say they can’t make such judgments unless providers report in a standardized manner such factors as the condition of patients upon entering the hospital and the number of in-hospital complications (such as infections) as well as death rates, cost figures and the other kinds of patient care statistics currently reported in California and other states.

Employers, who pay about a third of the nation’s bloated health-care bill, won’t ease the pressure on providers to give them what they want, said Charles O. Schetter, the Los Angeles-based director of the McKinsey & Co. consulting firm’s health-care practice. “The fact is that the information that is currently available is spotty. There is a great deal of difficulty in measuring value from what we have now,” he said.

If the movement for more comparative information is successful, some health-care analysts say it will revolutionize how America--especially big business and government--shops for health care.

“Such information would have a profound and far-reaching impact on how we channel health-care dollars, and subsequently, on the quality of care we receive,” said Peter Boland, a Berkeley-based health-care consultant.

Pressure from large Pennsylvania businesses, particularly Hershey Food Co., spurred the Pennsylvania legislature to mandate a new detailed, standardized reporting system in 1986. The Pittsburgh report was the first involving a big city with several Fortune 500 employers.

Hershey is also promoting a similar bill now before the California legislature that would cover hospitals and certain outpatient surgical centers. The bill, introduced by Rep. Bruce Bronzan (D-Fresno), passed the Assembly last week and is awaiting Senate action. It has the support of the California Business Group on Health, the California Chamber of Commerce and several labor unions, but is opposed by the California Association of Hospitals and Heath Systems.

Currently in California, those responsible for paying medical bills compare hospital performance by using data, including cost figures and death rates, collected and published by the Office of Statewide Health Planning, Boland said. “This data is limited and cannot be used to show whether medical treatment was necessary or effective. Current data collection does not get at quality, nor does it get at hospital efficiency as well,” Boland said.

The requirement to report the severity of a patient’s illness upon entering the hospital is an important factor in Pennsylvania and in the California proposal, he added. When hospital mortality rates are reported in California and other states, he said, hospitals with higher-than-average rates typically respond that “our patients are sicker than usual,” he said. Hospitals that show longer than average lengths of stay for their patients may make the same claim, he said.

“While these claims may be true in particular cases, they are not true across the board because everyone cannot be sicker than average,” he said. Information on the condition of patients upon entering the hospital would give health-care purchasers the basis to evaluate such claims, he said.

The hospital association opposes the Bronzan bill for several reasons, including the cost to hospitals of providing the data, said Michael Dimmitt, the association’s vice president for research and management information systems. Hospitals are already significantly under-funded for services they provide to uninsured patients, he said, and this measure provides no additional compensation for data collection.

The association opposes the bill because its hospitals believe the bill is fundamentally a cost-containment measure and if more cost containment is going to be imposed on them, the state should first resolve the issue of providing “a program to take care of the medically uninsured,” he said.

Pennsylvania hospital officials estimate that the program has cost about $30 million to implement, or $4 to $17 per patient. Some analysts say the cost in California would be at the low range because of reporting systems already in place. Given that the average California hospital bill is more than $5,000, the extra dollars would not be significant, they add.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.