Researchers Optimistic on Development of Vaccines

- Share via

SAN FRANCISCO — Large-scale tests of AIDS vaccines in uninfected volunteers may begin in two to four years and specialized tests to determine if the vaccines can protect the unborn fetuses of infected pregnant women could begin in 1991, leading vaccine researchers predicted Friday at the international AIDS conference here.

Buoyed by preliminary successful tests in monkeys and chimpanzees and a better understanding of what elements might be most important in an effective vaccine against the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), the researchers effused an optimism that has been lacking at earlier AIDS conferences.

“I anticipate that we will have a working vaccine in humans by the year 2000,” said Michael Murphy-Corb of the Delta Regional Primate Center in Lousiana.

Wayne Koff, a vaccine researcher with the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, said “the optimism toward the feasibility of a vaccine is increasing.”

Koff said that “within two to four years we will have significant enough information from animal and human testing to narrow the field of vaccine candidates. From those, the candidates to be tested in large-scale field trials will be selected.”

But a cautionary note was sounded by Josef Mannhalter, an Austrian researcher. One of two chimpanzees apparently immunized against HIV suddenly developed clear evidence of infection 28 months after being exposed to the virus, he said. The other chimpanzee has remained uninfected for a longer period.

Koff and others said it might take less time to select and test a vaccine to protect the unborn fetuses of infected pregnant women than to develop a vaccine for use in high-risk individuals or the general population.

Once such a vaccine product is shown to be safe in humans and effective in animals, it might be used to inoculate infected women before they give birth. By boosting the mother’s immune system, it might be possible to protect the fetus against infection with the virus.

Because an infant can be checked for HIV infection soon after birth, such a study might take only about a year to complete. Currently, about one-third of infants born to HIV-infected mothers become infected.

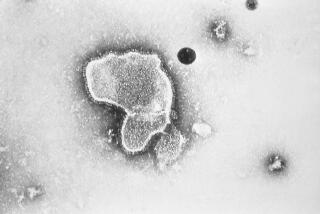

Vaccines work by inducing the body’s immune system to produce molecules known as antibodies that protect against infection.

In separate experiments, three American research teams, at the Delta Regional Primate Center, UC Davis and the New England Regional Primate Center in Massachusetts, have successfully immunized monkeys against simian immunodeficiency virus, a monkey virus that is very similar to HIV.

There also have been three successful experiments in which chimpanzees have been immunized against HIV infection--from researchers at Immuno AG in Vienna, Genentech in South San Francisco and the Pasteur Institute in Paris.

Another key advance is a better understanding of an area of the protein that covers the AIDS virus, known as the V3 loop. Findings from vaccine tests and human epidemiologic studies suggest that antibodies to the V3 loop may play a key role in conferring immunity to HIV infection and help to protect against transmission of HIV from mother to child.

In another presentation, Dr. Alexandra Levine of the USC Medical School updated experiments involving an AIDS immunization treatment for individuals who already are infected with the virus. This approach to AIDS therapy was developed by Dr. Jonas Salk, the polio vaccine pioneer.

All 82 patients involved in preliminary trials “remain alive and clinically well” at a median follow-up time of 2 1/2 years, Levine said. One person developed an AIDS-related pneumonia and three developed Kaposi’s sarcoma.