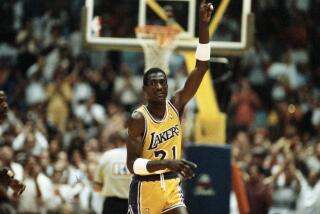

Cooper’s Renaissance : Former Laker Finds a New Life Playing in Italy

- Share via

ROME — Michael Cooper, a million-dollar immigrant to Italy known to his teammates as “the Farmer,” lofted a free throw that hit the rim, bounced off the backboard and settled back toward the basket--until a defender swooped up and knocked it away.

Said Cooper: “I thought to myself, ‘Hey--goaltending! He can’t do that!’ But I was wrong; in Italy the ball’s live after it hits the rim, so there was nothing to do but smile and run back down the court.”

At 34, after a dozen years as a Laker, Michael Cooper is relearning an old game in a new country. No longer a supporting character, he is cast as a budding star on a foreign stage.

There are pressures, disappointments and tough adjustments aplenty, but Cooper is coping. And Italian fans admire his generalship on the court and his gentlemanliness off it.

Cooper was the most valuable player in the Italian league’s all-star game; a fluke, said the Pasadena native, but he’ll take it. He has a contract that could keep him in Italy for at least two more seasons.

“I know there’s no going back,” he said. “The NBA is behind me, a wound I wouldn’t want to reopen.”

C-O-O-P! exults the overhead scoreboard at the home court of Messaggero-Roma, an in-contention team that was a tail-ender last year despite having Brian Shaw and Danny Ferry. Both are back in the NBA this season, which leaves Cooper playing with fellow import Dino Radja, a Yugoslav whose $3-million-plus salary makes him Europe’s highest-paid basketball player.

Under Coach Valerio Bianchini, the Messaggero theory is simple: Radja scores the points; Cooper gets the ball to him and Italian star Roberto Premier, and shuts down the other team’s big gun.

When it works, Messaggero wins. In a game against league-leading Benetton-Treviso, Radja, just back from a leg injury, scored 26 points. Cooper scored 18 and grabbed eight rebounds. Benetton’s American star, Vinny Del Negro, went into the game with a 29-point average. Cooper held him to 18. Messaggero won, 96-90.

Last Sunday, Premier scored 39 and Cooper 16 as second-place Messaggero beat Stefanel-Triete, 91-90, to raise its record to 11-5. All of this, mind you, on a team whose grammar is unabashedly fractured. Said Cooper: “I try to talk Italian as much as I can, so does Radja, and the Italians try English. We’re correcting one another all the time.”

For Cooper, a lot of work--and a role change--underlie Bianchini’s strategy.

“I came knowing that I liked Italy and liking the idea of only one game a week because it means more time with my family,” Cooper said. “But Italian teams practice harder during the season than some NBA teams in training camp--two-a-days three days a week. The floor is harder here, too, like playing on New York blacktop. I’ve adjusted, but at first I had blisters on my feet and knees that were hurting.”

With the Lakers, for whom he averaged 11.9 points as an outside shooter known for defense, the 6-foot-6 Cooper played shooting guard or small forward. That has all changed under Bianchini, the former Italian national coach, of whom Cooper said: “He’s an NBA coach.”

In Italy, where he is averaging about 17 points a game midway through the season, Cooper occasionally plays his former positions and sometimes even power forward. But he is foremost Messaggero’s point guard, rallying and directing the team, moving the ball. Against Benetton, Cooper passed to Radja or his teammates three or four times for every shot he took.

His wife, Wanda, calls her husband Messaggero’s “go-to” man.

Incidentally, she has made her own adjustments to life abroad. Shopping? “Italian’s no problem!” she said. Driving? “Be a mad dog like everybody else.”

Said Michael Cooper: “I enjoy having to try to pull the team together, but it’s a lot of load on my shoulders. I understand better now about Michael Jordan, Kareem (Abdul-Jabbar) and Magic (Johnson).”

Against Benetton, two of Cooper’s baskets were three-pointers. That’s an easy adjustment: The three-point line is about a yard closer to the basket than in the United States.

There are other changes: The lanes are much wider in Italy, meaning less congestion and deeper penetration by the big men inside. Traveling seems to be an unknown infraction.

Cooper averaged about 20 minutes a game in the NBA. In the Italian pros, he plays about 39 minutes of a regulation game divided into two 20-minute halves.

“Everybody likes Cooper--the players, the fans, the press,” one Italian sportswriter said. “He hasn’t been spectacular, but he’s steady and a leader; the team’s glue.”

Messaggero, Cooper said proudly, leads the league in attendance.

Which is not to say that all is roses in the Eternal City. Italians are not good losers. When a basketball team loses, as Italian newspapers invariably tell the story, it is because its two foreigners played badly. When it wins, the reason--you guessed it--is because the Italians played well.

During a two-game losing streak, bills that the team had been paying began appearing at the Cooper house. One Sunday, a flu-stricken Cooper played despite a high fever. Messaggero lost, and next morning his 21 points were judged to have been “uninspiring.”

For Cooper, though, the balance thus far is as positive as his mission is clear.

“The Italians are a step or two off the NBA in their knowledge of the game,” he said. “We grew up with it and adapted mentally much earlier, but Italian basketball has come a long way. It’s not our job to try and change it or to make it more like the NBA, but to give people what they want--a faster, more exciting game.”

Cooper’s nickname stems from the fact he has settled with his family in a distant and isolated rich man’s suburb about an hour north of the city. It is an area closer in ambience to Pacific Palisades than to Rome. “About as close to Rome as I want to get,” Cooper said.

Particularly for newcomers, the Italian capital can be intimidating. The Coopers smile with hard-won new wisdom when friends back in Los Angeles complain about traffic.

“Nothing in L.A. prepares you for this,” Wanda Cooper said. “There are rules there, and most people follow them--like stopping at stop signs. But we like the rhythm and the values here; like the sense of family. Everything shuts down from 1 to 4 every afternoon because there are more important things than making another dollar. I can’t imagine that happening in the U.S.”

Rome is friendly to its new star. When English fails in restaurants, the Coopers willingly throw themselves on the mercy of the house specialty. They say they haven’t had a bad meal yet. Michael Cooper, up to 180, has added four pounds that even Bianchini’s incessant practices can’t shed.

“When we first came,” Wanda Cooper said, “there was a big poster that said, ‘A Black King (Cooper) for a White Prince (Radja).’ When there is talk of color in America it is not always complimentary, but here (the poster) meant exactly what it said.”

Said Michael Cooper: “People everywhere in Italy have been very cordial. I’m pretty sure there’s racism here, but it hasn’t been shown to me.”

The change that has become the hallmark of Cooper’s new career after a dozen years of success in the metropolis where he was born does not end on Italian basketball courts or highways. It comes home, too.

There is no hoop at the Cooper’s rented house in the suburbs, and one morning as his father wandered past, fifth-grader Michael Jerome Cooper II was drilling a soccer ball off the driveway wall. Young Michael fired a kick at his father, who moved lithely to the ball . . . and caught it. Some adjustments overseas are tougher than others.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.