PRIVATE FACES, PUBLIC SPACES : Spinning a Reality in the World of Fantasy

- Share via

In the back of a graceful old building on West Third Street, a seamstress has her studio. There is hardly a sound here. She works alone by the huge north window looking out over lemon trees, other roofs, other skylights. A Mediterranean village has this feel: whitewashed, secretive. Bolts of cloth are lined up precisely on the shelves, spools of colored thread collected in a box, soft chiffons, seams pinned painstakingly, tiny stitches barely visible--to look around is to look back. The stillness, the workmanship--they talk of other times.

Alicia Leon Luna grew up in a house that was ordered this same way. It was high in the Andes, with a large walled garden around it, full of peach, plum and fig trees, flowers and children. There were maids in the kitchen, the laundry, the sewing room. Until she came to Los Angeles and slept in the maid’s room, she had never worked in a kitchen nor tended her own clothes.

She had dreamed of leaving Ecuador, her small town among the fruit orchards, her father’s sadness during the hard times that came to them. She went away to Los Angeles for an adventure, a vacation--and hardly noticed the first four years passing. Thus are lives shaped.

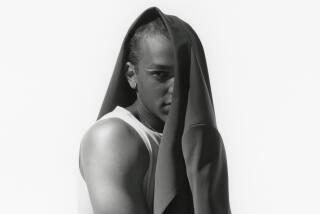

She is one of 11 children. A sister is in Australia now, another in Panama; the past will never be quite the same again. And Alicia Leon Luna lives alone and sits alone at her sewing table, fitting silken tape over inside seams, making buttons by hand, piping and rolling them, stitching and creating. The large serious eyes, the quiet face that rarely smiles--it has become a craftsman’s face, concentrated, intently focused. The child who was pampered and adored is the woman whom no one spoils. She is stronger for it, independent, proud--and grateful, oddly enough.

She is grateful to the women who have been kind to her. The one who heard her cry herself to sleep behind the maid’s room wall and drew her out with sweetness. The one who showed her how to sew preachers’ robes, $10 a week, who watched as she fumbled with her delicate fingers, and did not fire her. The ones who taught her to be strong in the years of snobbery and rejection, taken so often for the housekeeper, the servant, as if that were her natural inheritance. “They thought sometimes I was any Spanish-speaking person hungry for work. But I never liked to take little, I would not take just anything. I always like to work my way up, to be on top.”

She has worked in a factory, served the grand ladies of Bullock’s Wilshire, opened her own shop once offering alterations and dressmaking--trying always to please. “I encountered a lot of unpleasant people.” So mostly, she is grateful to the costume designer who saw past the “little Spanish dressmaker” and recognized fire, art, relentless perfection. Slowly, she has drawn into the world of films, of private customers, of security and respect. “From the beginning, this woman made me feel confident. If I disappointed her or not, she never treated me that way. She gave me the courage to go ahead.” The gift of recognition.

On the rail of her studio hang the clothes she is altering for others: for films, for stars, for the famous who still awe her. Next to them hang the clothes she has made for herself: a sapphire-blue day dress with intricately stitched buttons, an ethereal chiffon for evening. Romantic clothes for a sensible woman with a sensible face who works as many hours in the day as she has to; the clothes of that girl in Ecuador watching her handsome, elegant father who danced so beautifully, dreaming of one life and settling for another.

“I think most people are afraid to try. As long as they make enough to eat and to have some clothes, they go by day by day. I always thought if someone could have something, I could work hard and have it, too. If someone could go somewhere, I could do it, too. My father once said, ‘I’m afraid, honey, you’re going to be alone.’ I am alone. But I’m not lonely.”

Behind the barrier of language and false assumptions, how many other such spirits must there be who are afraid to fly?

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.