A Summit Aimed at Keeping Two Friends From Colliding : Bush and Kaifu meet in Newport to get U.S.-Japan relations back on track

- Share via

California seems to provide a rejuvenating setting for U.S.-Japan relations. For the second year in a row, President Bush will venture from the Beltway--and Prime Minister Toshiki Kaifu will travel across the Pacific--for a West Coast tete-a-tete aimed at calming down roiling U.S.-Japanese relations.

The two leaders will meet in Newport Beach today to make up for a spring trip to Tokyo that the President postponed in order to meet with the Persian Gulf allies. The Japanese prime minister is eager to reaffirm the U.S.-Japan global partnership, strained anew by Tokyo’s disappointing response to the Gulf crisis.

Tokyo hopes to recoup lost respect and status at a time when Washington is short on patience and long on criticism. Polls reveal that grass- roots America feels let down by Tokyo’s checkbook diplomacy in the Gulf; in Congress, Tokyo sometimes seems to have replaced Moscow as everyone’s candidate for knocking. Despite a hefty $11-billion contribution to the multinational forces in the Gulf, the perception is that an unsure and reluctant Tokyo didn’t carry its fair share. For its part, Tokyo cries foul, noting that it did as much as possible considering its constitutional ban on sending troops overseas. It’s getting very tired of what it sees as unrelenting Japan-bashing.

Such emotions are damaging to U.S.-Japan relations at a time when the two nations need to work more closely than ever on the mutual concerns of trade, the Mideast and Tokyo’s upcoming talks with the Soviet Union. The big challenge for Bush and Kaifu is to break an unsettling push-pull dynamic that is distorting the relationship. Washington finds itself doing a whole lot of pushing--playing hard ball with Tokyo to secure changes in trade policy. In response Tokyo does a whole lot of pulling--relying and even encouraging foreign pressure-- gaiatsu-- before mustering the political will to instigate changes within Japan. The fallout from such a dynamic engenders a sometimes hegemonic attitude on the part of Washington that results in bullying consensus-driven Tokyo into making promises public before it can secure the political clout to deliver them.

Ironically enough, U.S.-Japan relations are turning frosty precisely when the fundamentals of their trading relationship are improving--albeit slightly. The U.S. trade deficit with Japan has been less terrible each year for the past four years, narrowing to $41.1 billion in 1990--the lowest level since 1984. Japan is the largest importer of U.S. agriculture. Meanwhile, Tokyo and Washington have resolved many major trade issues. Washington, to be fair, has not been particularly speedy in delivering on its promises to cut the U.S. budget deficit, shore up savings and improve the education system.

Still, with $40-plus billion still to go on the trade deficit account, and with U.S. exports a driving force in the nation’s recovery from recession, trade is important to the Bush Administration. Unfortunately, the United States still does not have the trade opportunities in Japan that Japan has here. Tokyo erects too many barriers to trade.

Tokyo’s continuing ban on rice imports has been a particularly divisive issue. The Administration was disappointed by Tokyo’s lack of support on agricultural issues at multilateral trade talks last December. A recent threat by Japanese agricultural officials to take legal actions against the USA Rice Council for displaying American-grown rice in Japan did little to relax the relationship. Perhaps Tokyo will address the rice issue after Japan gets through its local elections Sunday.

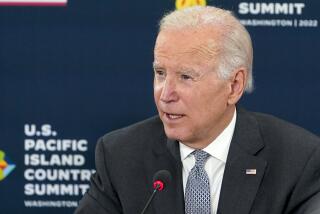

The image of Bush and Kaifu as pals makes for a wonderful photo, but it oversimplifies the realities of the U.S.-Japan connection, complicated by differences in cultures, political systems and priorities. Still, the mutual and proper priority is in improving U.S.-Japan relations. The best way to achieve that is to work at it constantly, step by step. Today’s summit meeting won’t accomplish a great deal, perhaps, but it is hard to believe that it can hurt.

TRADE IMBALANCE

U.S. merchandise trade deficit with Japan (in billions):

1980: 9.9

1981: 15.8

1982: 16.8

1983: 19.3

1984: 33.6

1985: 46.2

1986: 55

1987: 56.3

1988: 52.1

1989: 48.4

1990: 41.1

Source: U.S Department of Commerce

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.